A HAPTIC GEOGRAPHY OF BOULDERING "It lets you use

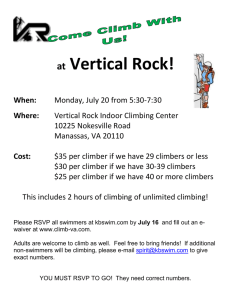

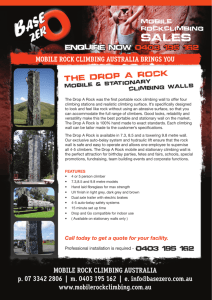

advertisement