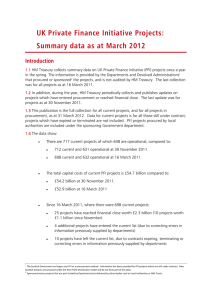

Michael G.Pollitt Abstract

advertisement