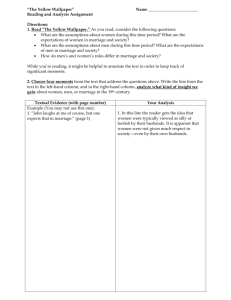

Marriage (In)equality: The Perspectives of Adolescents and Emerging Adults With Lesbian,

advertisement