M Maassssaacchhuusseettttss IInnssttiittuuttee ooff T Teecchhnnoollooggyy E

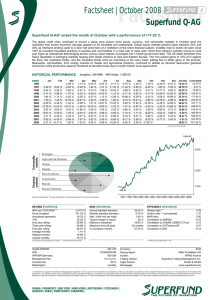

advertisement