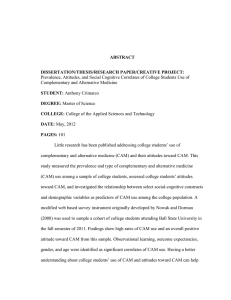

USE OF COMPLEMENTARY AND ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE AMONG RURAL MONTANANS by

advertisement