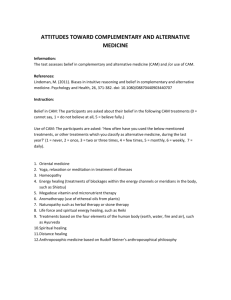

Complementary and alternative medicine use in children with chronic health... by Laurie Bernhardt Glover

advertisement