Self-directed violence CHAPTER 7

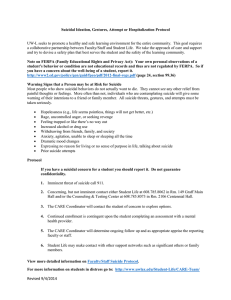

advertisement