The death of postfeminism : Oprah and the Riot Grrrls... by Cathy Sue Copenhagen

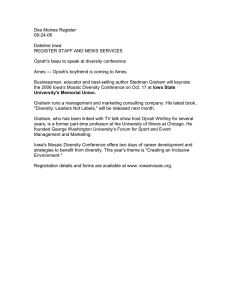

advertisement