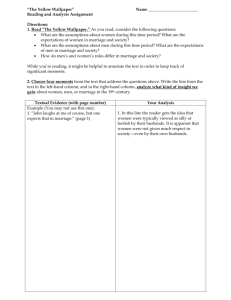

The will of the people : popular support for marriage... by Jason Keith Nye

advertisement