Faith, hope, and ethnicity : St. Marys Parish in Butte

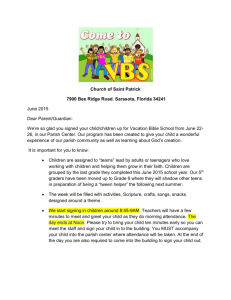

advertisement