Administration & Society

http://aas.sagepub.com/

Modeling Nonprofit Employment : Why Do So Many Lesbians and

Gay Men Work for Nonprofit Organizations?

Gregory B. Lewis

Administration & Society 2010 42: 720 originally published online 27 August

2010

DOI: 10.1177/0095399710377434

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://aas.sagepub.com/content/42/6/720

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Administration & Society can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://aas.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://aas.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations: http://aas.sagepub.com/content/42/6/720.refs.html

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010

377434

AAS

Modeling Nonprofit

Employment: Why Do So

Many Lesbians and Gay

Men Work for Nonprofit

Organizations?

Administration & Society

42(6) 720­–748

© 2010 SAGE Publications

DOI: 10.1177/0095399710377434

http://aas.sagepub.com

Gregory B. Lewis1

Abstract

Why are people with same-sex partners more likely than married people

to work for nonprofit organizations (NPOs)? Analysis of 2000 Census data

suggests that smaller gay–straight pay disparities for men in the nonprofit

sector, occupational choices, and ability to afford nonprofit employment

explain some overrepresentation of partnered gay men but not of partnered

lesbians. Even after controlling for all these factors, people with samesex partners remain more likely than married people to work for NPOs,

suggesting that a strong desire to serve others is an important factor.

Keywords

sector choice, nonprofit employment, sexual orientation, pay disparities

People with same-sex partners are much more likely than married people to

work for nonprofit organizations (NPOs). As Americans generally see charitable institutions as performing more socially and morally responsible work

than private firms and governments, this overrepresentation of lesbians, gay

men, and bisexuals (LGBs) may surprise the majority of Americans who

1

Georgia State University, Atlanta

Corresponding Author:

Gregory B. Lewis, Andrew Young School of Policy Studies, Georgia State University, Atlanta,

GA 30302-3965

Email: glewis@gsu.edu

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010

721

Lewis

believe that homosexuals share hardly any of their moral values. Brooks

(2006) suggests that volunteering and giving to NPOs distinguishes between

the charitable and the selfish, and several studies indicate that most nonprofit

employees donate a share of their potential earnings by accepting lower pay

than they could earn working for a for-profit firm. Does the striking concentration of gay men and lesbians in the nonprofit sector indicate a misperception of the benevolence of LGBs or of NPO employees?

Using a 5% sample of the 2000 Census, I first establish that people with

same-sex partners are much more likely to work for NPOs than those with

spouses or opposite-sex partners. I then test two nonaltruistic hypotheses to

explain the disparity. First, LGBs’ overrepresentation in NPOs could be a

side effect of their residential and occupational choices or of other characteristics. If NPOs are concentrated in West Coast or Northeastern cities where

LGBs tend to live or if NPOs disproportionately employ people in occupations where LGBs work, for instance, LGBs could be more likely than others

to work for NPOs without preferring nonprofit employment. Second, partnered gay men and lesbians might have no stronger commitment to service

but be better able to afford to choose the nonpecuniary benefits of the nonprofit sector, because they are more likely to have a well-paid partner to subsidize their endeavors, less likely to have children to support, or face smaller

wage penalties in a less-discriminatory nonprofit sector.

Separate regression analyses by sex, sector, and educational level confirm

earlier findings that most workers make a financial sacrifice by choosing

nonprofit employment and that men with male partners earn less than comparable married men. They also reveal that gay–straight pay disparities for men

are markedly smaller in the nonprofit sector. (Women with female partners

earn about the same as married women in both sectors.) Logit analyses by sex

and educational level confirm that gender, education, occupation, industry,

location, and the size of sectoral pay differences all influence whether one

chooses nonprofit employment, though the analyses do not replicate earlier

findings that racial and ethnic minorities are more likely than comparable

Whites to work for NPOs. Even controlling for all these factors, however,

people with same-sex partners are more likely than comparable married people to work for NPOs, suggesting that altruistic motives help explain the

overrepresentation.

LGBs, Altruism, and Nonprofit Employment

Most Americans disapprove of LGBs. In five surveys since 2000, 52% to

57% say “sexual relations between two adults of the same sex” are “always

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010

722

Administration & Society 42(6)

wrong.” In 14 surveys since 2000, between 48% and 58% call homosexual

relations “morally wrong.” This moral disdain might just be for homosexual

sex and not for LGBs as human beings; however, “feeling thermometers”

that ask people to rate homosexuals and other groups on a scale from 0 to

100 based on the warmth of their feelings toward them show that “between

1984 and 2002, the American public moved from feelings that best can be

described as icy (a mean score of 30) to a temperature just a shade below

neutral (46)” (Egan & Sherrill, 2005). When the Washington Post (1998)

asked whether homosexuals “generally share most of your moral and ethical

values, some of your moral and ethical values, or hardly any,” only 6% said

most and another 29% said some; in contrast, 33% chose hardly any and 24%

volunteered none.

This made all the more surprising tentative findings that people with

same-sex partners are more likely than married and heterosexually partnered

people to work for NPOs (Badgett & King, 1997; Lewis, 2006), suggesting

higher levels of benevolence among LGBs. Nonprofit employees are widely

reputed to be more altruistic than those in the for-profit sector (Jeavons, 1992;

Mirvis, 1992; Mirvis & Hackett, 1983)—or at least to have stronger political

or religious commitments to social change (Onyx & Maclean, 1996; RoseAckerman, 1996). The opportunity to serve others is a major attraction of

work in the nonprofit sector, allowing many NPOs to attract volunteer labor

and to pay lower salaries than for-profit firms to employ comparable workers

(Frank, 1992; Preston 1989, 1990; Weisbrod, 1983). Nonprofit employees,

especially managers and professionals, appear to donate part of their labor by

accepting below-market pay (Frank, 1996; Hansman, 1980; Preston, 1989;

Rose-Ackerman, 1996).

NPOs can attract employees despite low wages partly because many people find nonprofit work more socially responsible, meaningful, and personally rewarding than for-profit or government employment (Frank, 1996;

Light, 2002; Mirvis, 1990; Mirvis & Hackett, 1983). As opportunities to help

others or benefit society increase job satisfaction even for people who do not

prioritize helping others in choosing a job (Lewis & Frank, 2002), this may

compensate for lower pay in the nonprofit sector (Preston, 1989, 1990). NPO

employees have higher job satisfaction than similar individuals in the forprofit sector (Benz, 2005). Public administration scholars have devoted much

effort to describing the impact of public service motivation on seeking or

keeping government jobs (Crewson, 1997; Karl & Sutton, 1998; Perry &

Wise, 1990; Rainey, 1982; Wittmer, 1991). Similarly, those who value service to others or prioritize meaningful work over high pay should be more

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010

723

Lewis

likely to choose employment in the nonprofit than in the for-profit sector

(Light, 2002).

Several economists dispute the claim of low NPO pay, however, which

would make altruistic explanations for choosing nonprofit employment

unnecessary. Reanalyzing data used by Weisbrod (1983), Goddeeris (1988)

found no pay disadvantage for public-interest lawyers. Using 1990 Census

data, Leete (2001) concluded that the pay disadvantage to working in the

nonprofit sector is disappearing. Analyzing 1994-1998 Current Population

Survey data, Ruhm and Borkowski (2003) found that NPO pay is competitive. Although economists often find that government pays above-market

rates (e.g., Belman & Heywood, 1989; Gyourko & Tracy, 1988; Moulton,

1990; Smith, 1976—a conclusion widely rejected in the public administration community—they do not find that NPOs pay better than the for-profit

sector.

Why Do LGBs Choose Nonprofit Employment?

Before seeking altruistic explanations, we need to consider whether LGBs’

overrepresentation in the nonprofit sector is driven by their residential and

occupational choices or by other personal characteristics rather than by a

desire to work for NPOs. LGBs are much more likely than heterosexuals to

live in urban areas, on the West Coast, and in New England (D. A. Black,

Sanders, & Taylor, 2007; Black, Gates, Taylor, & Sanders, 2000, 2002; Gates

& Ost, 2004). If nonprofit jobs are more urban than for-profit jobs and concentrated in those areas, high numbers of LGBs in NPOs would naturally

result.

LGBs also have different occupational distributions than heterosexuals

(Badgett, 2001; Blandford, 2003). As occupations differ substantially

between the for-profit and nonprofit sectors (Ruhm & Borkowski, 2003),

overlapping distributions could lead to disproportionate numbers of LGBs

working for NPOs. Among other differences, both gay men and lesbians are

more likely than heterosexuals to choose occupations atypical for their gender (Badgett, 2001; Blandford, 2003). Black et al. (2007, p. 65) show that the

average man in a same-sex couple works in an occupation where 47% of the

workers are women; for the average heterosexually coupled man, only 39%

are women. The average woman with a female partner works in an occupation where 55% of her coworkers are women; for women with male partners,

the percentage is 60%.

The nonprofit workforce is predominantly female (Benz, 2005; Mirvis,

1990; Mirvis & Hackett, 1983; Onyx & Maclean, 1996; Preston, 1989),

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010

724

Administration & Society 42(6)

largely, according to Preston (1990), because of the sector’s higher concentration of “traditionally female” jobs. Leete (2000, p. 440) notes that the average man in the nonprofit sector works in an occupation that is 79% female,

whereas in the for-profit sector he works in an occupation that is only 41%

female. Gay men’s higher propensity to work in more “female” occupations

could help explain their disproportionate nonprofit employment (though not

that of lesbians).

Ruhm and Borkowski (2003) also note that NPO employees “are concentrated in eight narrowly defined industries” (p. 1006). If LGBs are disproportionately drawn to those industries, they will be more likely to work for

NPOs. As people consider most of these industries to be more socially

responsible than others (Frank, 1996), however, choosing them could demonstrate an altruistic bent even in the absence of nonprofit employment.

Second, LGBs may have no stronger desire to serve others than heterosexuals do, but they may be more able to afford to choose nonpecuniary over

material rewards. Black et al. (2007) argued that the greater difficulty and

expense same-sex couples face in having or adopting children makes them

more likely to be childless, which, in turn, loosens their time and money constraints, especially for couples with two male earners. This can lead to greater

consumption of leisure activities; men in gay male couples work somewhat

fewer hours than men in heterosexual couples and are more likely to live in

expensive, “high-amenity” cities (Black et al., 2002, 2007).

It may also lead to more nonprofit employment. If socially responsible

work is morally rewarding but comes at a financial cost, those with more

financial resources (or fewer constraints) should be more likely to choose

socially responsible work (Frank, 1996). This could help explain why college

graduates are much more likely than high school graduates to work for NPOs

(Mirvis, 1990; Mirvis & Hackett, 1983; Preston, 1989, 1990): College graduates receiving below-market pay from NPOs still earn more than high school

graduates working for private firms. It may also help explain why women are

far more likely than men to work for NPOs: Wives’ pay typically comprises

a smaller share of household income than husbands’ pay, making a pay penalty for the wife less costly to the family. As lesbians are more likely than gay

men to have children and less likely to have a partner with a large paycheck,

however, affordability will explain less of the overrepresentation of lesbians

in NPOs.

Gay men may also be more able to afford nonprofit employment than married men if they face less wage discrimination in that sector. Several studies

find that gay men earn 15% to 30% less than comparably educated and experienced straight men, though lesbians may earn more than comparable straight

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010

725

Lewis

women (Allegretto & Arthur, 2001; Badgett, 1995; Barrett, Pollack, & Tilden,

2002; Berg & Lien, 2002; Blandford, 2003; Black, Makar, Taylor, & Sanders,

2003; Carpenter, 2004, 2005; Carpenter & Gates, 2008; Clain & Leppel,

2001; Jepsen, 2007; Klawitter & Flatt, 1998). Experiments show that employers are less likely to offer job interviews to lesbian and gay job applicants

(Crow, Fok, & Hartman, 1998; Hebl, Foster, Mannix, & Dovidio, 2002;

Weichselbaumer, 2003), supporting an attribution of gay men’s lower pay to

discrimination.

Because NPOs appear to discriminate less against women and minorities

than for-profit firms do, they may discriminate less against LGBs as well.

Preston (1990) attributed much of women’s concentration in the nonprofit

sector to smaller gender pay disparities—the cost to working in the sector is

lower for women than men. Leete (2000) found much lower variation in pay

in NPOs than in for-profit firms, especially at managerial and professional

levels, and much lower pay disadvantages for women and minority men. (She

attributes the pattern to the higher importance of pay equity in organizations

that rely on intrinsically motivated workers.) If LGB–straight disparities are

also smaller in NPOs, LGBs pay a smaller wage penalty for nonprofit

employment and may be attracted to a less discriminatory workplace.

Alternatively, lesbians and gay men might have a special preference for

working in the nonprofit sector. Having experienced societal disdain, LGBs

probably identify more with out-groups generally than heterosexuals do.

LGBs are also much more liberal than heterosexuals (Egan, 2009; Lewis,

Rogers, & Sherrill, 2003). If liberalism and out-group identification predict a

public service orientation, then nonprofit employment may attract LGBs

more than heterosexuals. On the other hand, LGBs are also strikingly less

religious than others (Egan, 2009; Lewis et al., 2003), which would tend to

discourage nonprofit employment, especially in the many religious NPOs.

Data and Method

The 5-Percent Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS) of the 2000 Census

provides detailed information on individuals in a random 5% sample of U.S.

households. In every household, the person who owns or rents the dwelling

is designated the householder, and others are identified by their relationships

to him or her. The Census lists a wide array of possible relationships (e.g.,

husband/wife, housemate, boarder), including “unmarried partner.” If the

householder and the unmarried partner are the same sex, I classify them as

members of a same-sex couple.1 Because the PUMS provides no indicator of

the sexual orientation of those without partners, and because coupled and

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010

726

Administration & Society 42(6)

single individuals differ systematically, I follow the lead of most research on

LGBs using Census data and drop all people who do not live with a partner.

I restrict the sample to full-time, full-year workers (those who worked at

least 40 hr a week for at least 48 weeks during 1999) who were at least 18

years old. The Census long form asked individuals detailed questions about

their “chief job activity or business last week” and instructed those with multiple jobs to describe the one where they worked the most hours. After naming their employer, they indicated whether they worked for “a private-for-profit

company or business,” “a private not-for-profit, tax-exempt, or charitable

organization,” a “local government (city, county, etc.),” a “state government,”

the “federal government,” or for themselves or their family. Leete (2001)

noted that data processors checked responses on sector “for consistency with

answers to questions on employer name, location, industry, and occupation”

and “could use a directory of company names to identify the correct . . . legal

form of an organization” (p. 145). Leete (2001) and Ruhm and Borkowski

(2003) concluded that although some nonprofit employees misidentified their

sector, those errors result in under- rather than overstatement of differences

between the sectors.

To establish whether higher percentages of those with same-sex than different-sex partners work for NPOs, I calculate the percentage of each sex and

couple type who work in each sector. To test whether overrepresentation of

LGBs in NPOs is a side effect of other choices, I calculate what percentage

of each group would work in each sector if all people in a particular location

or occupation or industry had the same probability of working in a particular

sector. For instance, I created a location variable with 345 values, one for

each PMSA (Primary Metropolitan Statistical Area) and one each for the nonmetropolitan areas in each state, calculated the percentage of all workers in

each location who worked in each sector, assigned that probability to each

worker in that location,2 then averaged the probabilities by gender and partner type. I used the same process for detailed occupation and industry codes.

I next examine whether most people would earn more working for private

firms than for NPOs, by running a series of regression models with the natural

logarithm of 1999 earnings as the dependent variable. Following Leete (2001),

I drop government employees and the self-employed and run separate models

for nonprofit and for-profit employees, allowing the two sectors to reward different characteristics (including sexual orientation) differently. Because most

analyses find very different pay patterns for lesbians and gay men, and because

many independent variables also affect male and female heterosexuals differently, I split the sample by sex. Because the nonprofit workforce is very highly

educated, I also analyze college graduates and others separately.

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010

727

Lewis

The key independent variables are two dummy variables coded 1 for people with same-sex or different-sex unmarried partners. The models include

fairly standard control variables. Education is measured in years for those

without college diplomas and as a set of dummy variables for college graduates (master’s degree, professional degree, and doctoral degree; those with a

bachelor’s as their highest degree are the reference group). Work experience

is estimated as “age – education – 6” and is entered in both linear and quadratic form to allow a curvilinear relationship. Weeks worked in 1999 and the

natural logarithm of hours worked in a typical week proxy for work effort and

344 dummy variables for the location (described above) proxy for labor market conditions. I include four dummy variables for race/ethnicity: Latino,

African American, Asian American, and Other or Mixed Race. Non-Hispanic

Whites are the reference group.3 Additional dummy variables indicate

whether the employee is a naturalized citizen, is not a citizen, has limited

English ability, or has a disability. I repeat all regressions, adding 25 dummy

variables for broad occupational category. If people choose their occupations

before finding their jobs, sectoral pay differences should control for these

choices; if employers place workers in occupations (e.g., manager), however,

they should not.

In Table 3, I convert regression coefficients into expected percentage differences in earnings by exponentiating all coefficients, subtracting 1, and

multiplying times 100. In Table 4, I estimate differences between people’s

expected earnings in the two sectors by calculating their expected pay twice,

once based on coefficients from a nonprofit regression and once from a forprofit regression, and subtracting the latter from the former.

Next I model employment in the nonprofit sector, using logit analysis on

a dummy dependent variable coded 1 for employees of NPOs. I run models

separately by sex and college graduation status. I include education, work

experience, race/ethnicity, citizenship, English ability, and disability as control variables, but do not add hours or weeks worked. I also include three

variables indicating the percentage of all people in that location, occupation,

or industry who work for NPOs.4

To capture how well an individual can “afford” NPO employment, I

include several variables. First, the smaller the expected nonprofit pay penalty from the previous regressions, the more likely nonprofit employment

should be. Second, the greater the household resources, the more likely nonprofit employment should be. The model includes a dummy variable coded 1

if the partner/spouse works at least 20 hr per week and the natural logarithm

of the partner’s earnings (coded 0 for those whose partners are not employed).

Third, children increase a household’s expenses, making nonprofit employment

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010

728

Administration & Society 42(6)

less affordable. Dummy variables for children younger than age 18 years

and those younger than age 6 years in the household should have negative

coefficients.

To determine which of these factors best explain sectoral employment differences between LGBs and married people, I run many variations on each

logit model. To a bivariate model that only includes couple type, I add (separately) industry, occupation, location, education, work experience, race/ethnicity/citizenship, children, partner’s work status, or expected salary

differences to see how the Has Same-Sex Partner coefficient changes. If

LGB–straight differences on that independent variable contribute to the gross

employment differences of Model 1, then the coefficient will shrink when

that variable is added to the model. Because the order of entry could matter,

I also start from the “full” model and drop each variable (or set of variables)

individually to see how the Has Same-Sex Partner coefficient changes. This

time, if LGB–straight differences on that variable contribute to the gross

employment differences, the Has Same-Sex Partner coefficient should grow

when I fail to control for it.

Findings

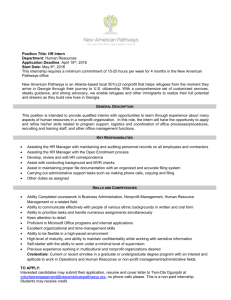

Descriptive Statistics

The nonprofit sector employs a disproportionately female, college-educated,

and LGB workforce (Table 1). NPOs employed 5.9% of the full-time workforce in 1999 but 9.5% of partnered women and 11.9% of partnered college

graduates. Men with male partners were more than twice as likely as married

men to work for NPOs (10.3% vs. 4.6%), and women with female partners

were about one quarter more likely than married women to do so (13.7% vs.

10.6%).

Although nonprofit employment varies widely by location, residential differences cannot explain the large number of LGBs working for NPOs. If

LGBs and heterosexuals living in the same PMSA had identical probabilities

of working for NPOs, 6.6% to 6.8% each group would work for NPOs (Panel

3). Differences in occupation and industry matter far more. If LGBs and heterosexuals in the same occupation were equally likely to choose nonprofit

employment, men with male partners would be substantially more likely than

married men (7.9% vs. 5.0%) and women with female partners would be

slightly more likely than married women (10.4% vs. 9.9%) to work for NPOs

(Panel 4). Differences would be even larger if LGBs and heterosexuals in the

same industry had the same probability of working for NPOs (8.4% vs. 4.7%

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010

729

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010

Actual distribution

All employees

Men with male partner

Married men

Men with female partner

Women with female partner

Married women

Women with male partner

College graduates only

Men with male partner

Married men

Men with female partner

Women with female partner

Married women

Women with male partner

Expected distribution (all employees)

Based on location

Men with male partner

Married men

Men with female partner

Women with female partner

Married women

Women with male partner

6.7

7.4

7.0

12.4

14.0

8.7

65.4

68.8

75.4

49.0

53.6

65.5

76.6

76.1

76.1

75.9

76.1

76.2

15.5

9.4

6.6

21.7

16.8

14.0

6.7

6.6

6.7

6.8

6.6

6.8

7.3

7.3

7.3

7.3

7.2

7.3

5.2

7.0

5.0

8.9

8.3

5.1

4.4

5.1

5.1

5.1

5.2

5.1

7.6

7.6

6.3

13.1

11.3

8.2

5.0

4.5

3.0

8.3

6.6

4.3

(continued)

4.1

5.5

2.9

3.9

4.1

3.0

4.7

6.8

4.7

3.8

4.3

3.6

5.0

4.8

4.8

4.9

4.8

4.8

Local

State

Federal

government government government

75.4

78.3

86.3

65.1

70.4

80.1

For-profit

10.3

4.6

2.7

13.7

10.6

7.5

Nonprofit

Table 1. Actual and Expected Percentage Working in Each Sector

730

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010

76.8

78.7

85.1

67.5

70.0

8.4

4.7

3.1

11.3

10.5

8.1

Women with male partner

78.6

76.0

78.5

83.2

67.7

70.9

76.7

For-profit

7.9

5.0

3.4

10.4

9.9

7.9

Nonprofit

Based on occupation

Men with male partner

Married men

Men with female partner

Women with female partner

Married women

Women with male partner

Based on industry

Men with male partner

Married men

Men with female partner

Women with female partner

Married women

Table 1. (continued)

5.6

5.5

6.7

5.3

8.6

8.7

6.0

7.0

6.0

8.7

8.1

6.1

4.5

5.5

4.5

3.3

8.0

6.6

5.5

4.4

3.6

7.7

6.6

5.3

3.2

4.6

5.1

3.7

5.4

4.6

4.1

3.7

5.4

3.2

4.6

4.2

Local

State

Federal

government government government

731

Lewis

for men, and 11.3% vs. 10.5% for women, Panel 5), though industry choice

may be too similar to sector choice to be an appropriate independent variable.

Still, actual LGB employment in NPOs is higher than that predicted by either

occupation or industry.

People with same-sex partners work for somewhat different industries

than married people within the nonprofit sector (Table 2). NPO employees

with same-sex partners are more than twice as likely as married NPO employees (6 times for men) to work for museums and art galleries; nearly twice as

likely to work for civic, social, and advocacy organizations; and about one

half more likely to work for universities. They are only half as likely to work

for elementary and secondary schools and only one fourth (men) to one half

(women) as likely to work for religious organizations.5 Coupled gay men are

also about one half more likely than married men to work for hospitals or

other health NPOs, though coupled lesbians are somewhat less likely than

married women to do so.

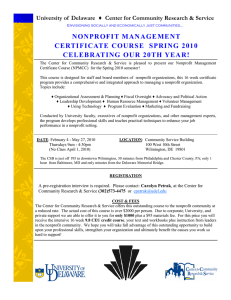

Earnings Differences

As in previous studies, men with male partners earn significantly less than

similar married men (Table 3). However, gay–straight pay disparities for

men are twice as large in the for-profit as in the nonprofit sector (17.9% vs.

8.6% for college graduates and 15.9% vs. 8.5% for those without college

diplomas).6 Narrower gay–straight pay gaps in the nonprofit sector echo

smaller gender and race pay disparities in the sector (Leete, 2000; Preston,

1990), though my findings are somewhat mixed on race. In contrast, women

with female partners earn about the same as comparable married women in

both sectors among college graduates and 5% more among women without

college diplomas, with or without controlling for occupation.

The vast majority of nonprofit employees would be expected to earn more

if they worked in for-profit firms, but expected earnings differences vary

widely across groups. Among people who worked for NPOs, 97% of male

college graduates, 92% of men without college diplomas, 85% of female college graduates, and 48% of women without college diplomas had higher

expected earnings in the for-profit sector. Pay penalties are higher for college

graduates than for others and for men than for women (Table 4). Average

expected earnings differences ranged from 32% for male college graduates to

0 for women without college diplomas. Racial differences were small for

women without college diplomas; for others, Whites typically paid a larger

penalty than minorities.

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010

732

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010

Male

partner

20.8

5.5

4.0

7.4

13.1

10.6

9.9

6.1

4.2

0.7

6.7

11.3

Hospitals

Religious organizations

Elementary and secondary schools

Family and child services

Colleges and universities

Other health

Civic, social, and advocacy organizations

Savings, insurance, and other financial services

Business and professional organizations

Labor unions

Museums and art galleries

Other

Table 2. Organizations That Employ Nonprofit Workers

18.0

21.3

8.8

5.7

10.0

4.8

5.5

3.0

2.4

2.2

1.1

17.3

Wife

Men with

18.5

2.7

6.2

12.3

9.0

4.3

9.0

2.9

2.6

2.8

2.1

27.5

Female

partner

24.7

2.4

6.6

18.0

9.7

10.4

10.9

1.8

3.0

0.6

1.5

10.7

31.1

5.6

12.8

13.6

6.0

8.1

6.4

4.6

2.1

0.5

0.9

8.4

27.1

1.2

6.0

19.2

5.0

9.5

10.1

5.1

2.7

0.7

1.6

11.9

25.2

11.8

10.7

10.5

7.7

6.8

6.2

3.9

2.3

1.3

1.1

12.6

Female

Male

All

partner Husband partner partnered

Women with

733

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010

Model 1. No occupational controls

Has same-sex partner

Has different-sex partner

Latino

African American

Asian American

Other or mixed race

Model 2. Controlling for broad

occupational category

Has same-sex partner

Has different-sex partner

Observations

−8.5**

(2.84)

−11.0**

(9.69)

−14.3**

(12.37)

−17.9**

(19.19)

−17.8**

(8.30)

−13.2**

(7.53)

−9.9**

(3.54)

−10.8**

(10.12)

30,065

−15.9**

(21.91)

−13.5**

(88.69)

−14.9**

(75.43)

−19.0**

(103.61)

−21.2**

(57.12)

−13.2**

(39.00)

−14.7**

(20.83)

−13.3**

(83.60)

949,071

−16.2**

(14.32)

−14.0**

(28.32)

320,646

−17.9**

(15.40)

−16.8**

(33.31)

−20.0**

(33.71)

−23.4**

(41.57)

−8.7**

(15.64)

−18.6**

(21.02)

−13.9**

(6.56)

−12.2**

(8.12)

43,100

−8.6**

(3.56)

−9.4**

(5.55)

−11.8**

(6.86)

−16.3**

(12.27)

−11.2**

(7.02)

13.2**

(5.54)

4.4**

(5.73)

−3.6**

(18.65)

517,521

5.0**

(6.21)

−5.2**

(26.41)

−10.2**

(39.42)

−10.0**

(42.39)

−8.9**

(20.65)

−7.6**

(17.49)

5.3*

(2.23)

−3.1**

(4.89)

52,900

5.0

(1.92)

−4.5**

(6.38)

−7.5**

(8.77)

−9.1**

(13.02)

2.9

(1.70)

−5.8**

(4.58)

−1.3

(1.06)

−7.9**

(14.36)

136,843

−1.6

(1.25)

−8.2**

(16.25)

−14.5**

(19.75)

−11.4**

(18.05)

−2.9**

(4.17)

−11.5**

(10.43)

−1.7

(1.14)

−3.7**

(4.26)

41,924

−1.4

(0.83)

−3.7**

(3.91)

−7.4**

(5.71)

−3.9**

(3.75)

4.4**

(3.14)

−5.4**

(2.94)

College graduate

For-profit Nonprofit For-profit Nonprofit For-profit Nonprofit For-profit Nonprofit

No college diploma

College graduate

No college diploma

Women

Men

Table 3. Expected Salary Differences, by Sector, Sex, and Education

734

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010

Male

without

diplomas

−2

−13

−6

−13

−4

−9

−7

−11

−12

Same-sex partner

Married

Different-sex partner

White

Asian

Black

Latino

Other

Total

−22

−33

−23

−34

−24

−22

−18

−24

−32

Male

college

graduates

−1

0

1

0

13

0

1

2

0

Female

without

diplomas

−19

−13

−12

−14

−2

−7

−6

−6

−13

Female

college

graduates

Expected percentage pay difference

Table 4. Expected Pay Differences Between Nonprofit and For-Profit Sectors

58

93

81

95

72

85

81

90

92

Male

without

diplomas

92

97

94

98

93

91

85

91

97

Male

college

graduates

51

48

46

49

7

49

44

36

48

Female

without

diplomas

93

84

83

88

54

76

68

67

85

Female

college

graduates

Percentage with negative difference

735

Lewis

Men with same-sex partners typically paid much smaller penalties than

married men. Among gay men without college diplomas, the expected pay

penalty was only 2%, and 42% were expected to earn more in the nonprofit

sector; in contrast, married men without diplomas paid a 13% penalty, on

average, and only 6% were expected to earn more in the nonprofit sector.

Among male college graduates, the expected pay penalty was much higher

for both those with male partners (22%) and those with wives (33%) and

nearly universal (92% and 97%, respectively), but again members of samesex couples faced less disadvantage in the nonprofit sector. In contrast,

female college graduates with female partners were more likely to pay a penalty (93% vs. 84%), and paid a larger one (19% vs. 13%), than married

women.

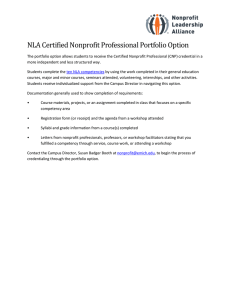

Choice of Sectors

In Table 5, Model 1 is a bivariate logit model for nonprofit employment, with

partner type as the only independent variable. The Has Same-Sex Partner

coefficients indicate that men with male partners are 3.4 percentage points

more likely than married men to work for NPOs if they do not have college

diplomas (6.5% vs. 3.1%) and 7.2 percentage points more likely to do so if

they are college graduates (19.2% vs. 12.0%). Women with female partners

are 1.6 points less likely than married women to work for NPOs among those

without college diplomas (8.0% vs. 9.6%) and 6.8 points more likely to do

so among college graduates (30.7% vs. 23.9%).

Changes in the Has Same-Sex Partner coefficients between Models 1 and

2 (the “full” model) suggest how much of the gross differences in nonprofit

employment can be accounted for by LGB–straight differences in industry,

occupation, location, pay gaps, partner’s pay, children, race/ethnicity, education, and work experience. Strikingly, adding the full set of control variables

only meaningfully changes the Has Same-Sex Partner coefficient for people

without college diplomas, shrinking it by about half for men (from .767 to

.421) but shifting it in the opposite direction for women (the significant

underrepresentation disappears, replaced by an insignificant overrepresentation). For college graduates, the Has Same-Sex Partner coefficient shrinks

only 10% for men, and it expands 15% for women. Holding the other variables at their means and comparing LGBs to married people of the same sex,

the predicted probability of working for an NPO is about 50% higher for

those with same-sex partners for men (1.7% vs. 1.1% for those with less than

a college diploma and 6.5% vs. 4.0% for college graduates) and for female

college graduates (18.4% vs. 13.2%).

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010

736

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010

No college diploma

Model 2

0.421**

(4.54)

−0.132**

(4.06)

0.943**

(8.42)

0.004

(0.08)

0.010*

(2.26)

−0.007

(0.32)

0.004

(0.16)

0.094**

(2.93)

−0.243**

(7.91)

−0.151*

(2.40)

Model 1

0.767**

(11.87)

−0.362**

(15.20)

Has same-sex partner

Has different-sex partner

Expected nonprofit earnings

disadvantage

Partner is employed at least

20 hr per week

Natural logarithm of

partner’s earnings

Household has children

younger than age 18 years

Household has children

younger than age 6 years

Latino

African American

Asian American

Model 1

0.509**

(6.61)

−0.181**

(3.75)

0.870**

(11.15)

−0.076*

(2.01)

0.029**

(7.18)

−0.015

(0.65)

−0.033

(1.30)

−0.107*

(2.07)

−0.283**

(5.86)

−0.110*

(2.45)

Model 2

College graduate

0.559**

(12.06)

−0.439**

(14.62)

Men

Table 5. Logit Model for Nonprofit Employment, by Sex and Education

−0.206**

(3.35)

−0.428**

(25.56)

Model 1

0.081

(1.00)

−0.038

(1.74)

0.494**

(5.13)

0.104*

(2.22)

−0.010*

(2.09)

0.009

(0.63)

0.018

(0.95)

−0.102**

(3.98)

−0.346**

(15.71)

−0.340**

(6.75)

Model 2

No college diploma

0.345**

(8.00)

−0.384**

(17.17)

(continued)

0.397**

(6.03)

−0.037

(1.12)

0.345**

(4.78)

0.066

(1.06)

−0.001

(0.18)

−0.011

(0.50)

−0.015

(0.58)

−0.254**

(5.54)

−0.418**

(11.14)

−0.223**

(5.23)

Model 2

College graduate

Model 1

Women

737

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010

Other or mixed race

Has limited English ability

Naturalized citizen

Not a citizen

Disabled

Years of education

Master’s degree

Professional degree

Doctoral degree

Work experience

Model 1

Men

0.017**

(4.78)

0.152**

(2.79)

0.176**

(3.40)

−0.012

(0.28)

0.166**

(3.95)

0.053*

(2.40)

0.064**

(12.52)

Model 2

No college diploma

Table 5. (continued)

Model 1

0.439**

(17.61)

0.406**

(14.72)

0.560**

(16.17)

0.022**

(5.69)

−0.143

(1.87)

−0.299**

(2.65)

−0.356**

(8.24)

−0.171**

(3.95)

−0.153**

(4.48)

Model 2

College graduate

Model 1

0.030**

(12.05)

−0.010

(0.24)

−0.031

(0.57)

−0.200**

(5.95)

−0.184**

(4.71)

−0.096**

(5.34)

0.116**

(21.52)

Model 2

No college diploma

(continued)

−0.127

(1.88)

−0.252*

(2.45)

−0.348**

(8.72)

−0.343**

(7.66)

−0.334**

(10.49)

0.281**

(13.52)

0.138**

(4.60)

0.396**

(8.14)

0.026**

(7.84)

Model 2

College graduate

Model 1

Women

738

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010

979,142

979,141

−0.000

(0.33)

0.024**

(35.19)

0.071**

(20.15)

0.080**

(223.41)

.0014

.4884

Note: Absolute values of z statistics are in parentheses.

*p < .05. **p < .01.

Observations

Work experience squared

Probability of nonprofit

employment in occupation

Probability of nonprofit

employment in metro area

Probability of nonprofit

employment in industry

McFadden’s pseudo-R2

Model 1

.0014

Model 1

363,747

−0.000

(1.23)

0.011**

(21.76)

0.089**

(23.88)

0.078**

(173.96)

.6163

Model 2

College graduate

363,747

Men

Model 2

No college diploma

Table 5. (continued)

570,423

.0021

Model 1

570,423

−0.000**

(5.51)

0.013**

(32.12)

0.088**

(34.21)

0.070**

(253.54)

.4213

Model 2

No college diploma

.0021

178,769

178,769

−0.000**

(2.74)

0.010**

(21.36)

0.100**

(29.50)

0.064**

(155.72)

.4673

Model 2

College graduate

Model 1

Women

739

Lewis

Industry and occupation are the most important predictors of nonprofit

employment, followed by location (based on standardized odds ratios; Long

& Freese, 2006, pp. 177-179). Although the McFadden pseudo-R2 values

range from .42 to .62 for the full models, they are only .02 to .08 when those

three variables are dropped. The percentage of people in one’s industry who

work for NPOs is by far the strongest predictor of whether one works for an

NPO, but industry choice does not explain the overrepresentation of LGBs in

NPOs. Only among less-educated men are those with same-sex partners disproportionately concentrated in industries with high nonprofit employment.

Adding the industry variable to the “bivariate” model shrinks the Has SameSex Partner coefficient for men without college diplomas from .767 to .565.

For male college graduates, adding or dropping the industry variable barely

affects the coefficient. For both female groups, controlling industry shifts the

coefficient in a positive direction, indicating that coupled lesbians are less

likely than married women to work in NPO-heavy industries.

The percentage of people in one’s occupation who work for NPOs is the

second-strongest predictor of NPO employment, and occupational choice

helps explain why gay men without college diplomas are overrepresented in

the sector. (The Has Same-Sex Partner coefficient drops from .767 to .427

when occupation is added to the bivariate model and rises from .421 to .505

when it is dropped from the full model.) For the other groups, adding or dropping the variable has little impact on the coefficient, or shifts it in the wrong

direction. Location affects sector nearly as much as occupation (it actually

changes the McFadden pseudo-R2 a bit more) but, as in Table 1, it does not

help explain why LGBs are more likely to work for NPOs. LGB–straight differences in nonprofit employment are slightly larger when location is controlled than when it is not (starting from either the bivariate or full model).

The ability to afford nonprofit employment makes some difference, especially for men. The smaller one’s expected pay penalty for nonprofit employment, the more likely one is to work for an NPO. Among male college

graduates, for instance, the average predicted probability of working for an

NPO was 16.3% for those whose expected pay was higher in the nonprofit

sector and only 11.8% for those whose expected pay was lower in NPOs.

Although the positive effect is highly significant for all four groups, it is not

large: a one-standard-deviation increase in relative pay only raises the probability of nonprofit employment by 0.3 to 1.5 percentage points (holding the

other variables at their means).

Having an employed partner increases a man’s probability of working for an

NPO, and the higher his partner’s earnings, the higher his probability of doing

so. For women, however, higher partner’s earnings lower the probability of an

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010

740

Administration & Society 42(6)

NPO job for those without college diplomas and have no effect for college

graduates. Having children does not significantly affect the probability for

working for an NPO for any group.

Affordability helps explain why men with male partners are more likely

than married men to work for NPOs, but it does not help explain sectoral differences for women. For men, the Has Same-Sex Partner coefficient is about

20% lower in the full model than in the same model without relative pay,

partner’s work status and earnings, and the presence of children; the bivariate

coefficient also drops by .12 to .15 when those variables are added in the

men’s equations. For the women, however, these variables have virtually no

effect on the Has Same-Sex Partner coefficient.

Additional education increases the probability of nonprofit employment

for all groups, as does work experience. The somewhat higher educational

level of men with male partners than of married men explains a small amount

of the sectoral difference. Somewhat surprisingly, given previous research on

the diversity of the nonprofit sector, African Americans and Asian Americans

were significantly less likely than comparable Whites to work for NPOs in all

four groups, and Latinos were significantly less likely to do so in three groups.

Limitations

Because Census data only identify LGBs who live with their partners, I

dropped the unpartnered and compared people with same-sex partners to married people. This choice of comparison group is particularly important for

men, because an extensive empirical literature shows that husbands make

substantially more than apparently comparable single men, even if they have

female partners (Antonovics & Town, 2004; Cornwell & Rupert, 1997;

Ginther & Zavodny, 2001; Gray, 1997; Korenmann & Neumark, 1991;

Krashnisky, 2004; Loh, 1996; Stratton, 2002). Three potential explanations of

the marriage premium for men, all finding some support in the research, suggest different implications of comparing partnered gay men to married men.

First, if employers discriminate in favor of married men, comparing coupled gay men to demographically similar married men is fair. Second, if marriage makes men more productive (e.g., because their wives specialize in

household production [cooking, cleaning, child-rearing], allowing the husbands to focus on their careers), however, this comparison may overstate pay

discrimination. To test this possibility, I restricted the sample to men whose

wives or partners work full-time to eliminate the single-earner households

where specialization is most likely; the unexplained gay–straight pay differences dropped for both college graduates and others in both sectors, but the

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010

741

Lewis

pattern of smaller disparities in the nonprofit sector persisted. Third, if more

productive men are more likely to marry (e.g., because women assess additional characteristics [not asked on the Census] that make men both more

desirable spouses and more productive workers), the comparison could also

be unfair, if gay men care less about productivity in choosing mates than

heterosexual women do. Selection into partnership may work differently for

LGBs than selection into marriage does for heterosexuals (Black et al. 2000;

Carpenter & Gates, 2008; Gates & Ost, 2004). However, wealthier and better-educated lesbians and gay men are more likely to have partners (Carpenter,

2003; Carpenter & Gates, 2008), suggesting that LGBs do consider productivity characteristics in coupling decisions, and the lower rate of coupling for

LGBs suggests that same-sex partnership is more selective than marriage.

This analysis also treats the ability to afford nonprofit employment as

exogenous. People without children and with well-paid partners or spouses

could be more likely to choose nonprofit employment, but couples where one

or both partners want to work for NPOs could choose to have both partners

work or not to have children. In the latter case, my findings would overstate

the impact of affordability. As those apparent effects were fairly weak, however, the bias appears minor.

This analysis also excluded the public sector, although Table 1 suggests

underrepresentation of gay men and college-educated lesbians in federal and

local government employment. Given a long history of explicit anti-LGB

discrimination in government employment (Johnson, 2004; Lewis, 1997), a

continuing ban on open LGBs in the military, and fairly weak protections

against discrimination in the federal service and most state and local governments today (Lewis & Pitts, in press), LGBs with high public service motivation may be drawn to nonprofit over public sector employment. That is,

altruistic impulses that might push heterosexuals toward public sector jobs

might direct LGBs to the nonprofit sector. The overrepresentation of LGBs in

NPOs swamps their underrepresentation in government, however, even after

controlling for the factors considered here (Lewis & Pitts, in press). Inclusion

of government employees might moderate but should not fundamentally

change the conclusions.

Conclusion

The nonprofit sector employed 7.2% of the U.S. workforce in 2004 (Salamon

& Sokolowski, 2006, p. 3), up from 6.4% in 1990, as nonprofit employment

has grown nearly twice as rapidly as the general economy for 15 years (Irons

& Bass, 2004, p. 3). Its ability to grow despite paying comparable workers

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010

742

Administration & Society 42(6)

substantially less than the private, for-profit sector indicates that superior

opportunities to help others and benefit society, along with other nonpecuniary benefits, play a key role in attracting qualified workers. Pay is not irrelevant, as the size of the financial penalty they pay individuals affects whether

nonprofit employment is chosen. A one-standard-deviation increase in relative pay only raises the probability of nonprofit employment by 0.3 to 1.5

percentage points, however, and other signs that a worker can afford to pay a

penalty (having an employed partner with high earnings and not having children) also have a limited impact. Nonprofit sector pay appears to be high

enough to ensure a qualified workforce but low enough to attract the more

altruistic portions of the labor force.

Thus, the overrepresentation of partnered lesbians and gay men in the nonprofit sector suggests they have higher levels of altruism or commitment to

social change, unless alternative explanations can be found. Partnered gay

men’s overrepresentation owes something to smaller earnings penalties,

greater likelihood of having employed partners whose salaries compensate

for those penalties, and lower probability of raising children. Even with all

these factors (including occupation and industry) controlled, however, gay

men’s odds of nonprofit employment remain half to two thirds higher than

those of comparable married men. These nonaltruistic explanations do an

even worse job of explaining the overrepresentation of partnered lesbians:

They do not differ from married women in ways that would predict overrepresentation in the nonprofit sector, but among college graduates their odds of

nonprofit employment are also 50% higher.

This pattern casts doubt on a widespread belief that LGBs share few, if

any, of the ethical and moral values of heterosexual Americans (Washington

Post 1998). It also clashes strongly with popular stereotypes that LGBs lead

hedonistic, self-centered, superficial lives. Black et al. (2002, 2007) have

examined how the different economic incentives LGBs face affect their life

choices but have tended to focus on greater consumption of leisure activities

and higher probabilities of living in expensive, “high-amenity” cities.

Researchers may want to consider whether different incentives also lead to

greater opportunities for service in other ways.

Managers of nonprofit organizations need to consider the implications of

their disproportionately LGB workforces. Explicit prohibition of discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and provision of domestic partner benefits may be especially important for NPOs in attracting and retaining

high-quality employees. NPOs may want to target more recruitment efforts at

the LGB community, for new employees as well as for volunteers and funds.

Diversity training may help heterosexual employees adapt to environments

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010

743

Lewis

where LGBs are likely to open on the job and develop organizational cultures

that value sexual diversity. Such efforts may increase NPOs’ competitive

advantage over private firms and governments for certain types of employees, though they may also make workplaces more challenging for religious

conservatives.

Scholars should also consider LGBs in their analyses of the nonprofit and

public sectors. Such marked LGB–straight differences in choice of nonprofit

employment suggest that representation and pay issues may also be important in government. Nondiscrimination protections could have important

impacts on recruitment and retention of both LGB and heterosexual employees or on the delivery of services. LGB and straight managers might differ in

style or effectiveness. Research has been hindered by the absence of good

data: None of the federal surveys ask for sexual orientation, and personnel

records do not include the information. A new sexual orientation question in

the 2008 American National Election Studies led to 5% self-identifying as

LGB and only 1% refusing to answer the question. A similar question on the

Federal Human Capital Survey could provide scholars large enough samples

to study a wide variety of issues.

Acknowledgment

An earlier version of this article was presented at the annual meeting of the

Association for Research on Nonprofit Organizations and Voluntary Action,

November 15, 2007, Atlanta, Georgia. I am grateful to Lakshmi Pandey for substantial help in working with the Census data and to Chester Galloway for excellent

research assistance.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author declared no conflicts of interests with respect to the authorship and/or

publication of this article.

Funding

This research was funded in part by the Williams Institute of the UCLA School of

Law.

Notes

1. When same-sex couples entered their marital status as “married,” the Census Bureau

changed their marital status and relationship codes, recoding them as “unmarried

partners.” Black et al. (2006) showed convincingly that most couples whose marital

and relationship status were “allocated” in this way had actually made an error in

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010

744

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

Administration & Society 42(6)

recording the sex of one of the spouses. Following their advice and the practice

of others (e.g., Carpenter & Gates, 2008; Jepsen, 2007), I have dropped everyone

whose sex, marital status, or relationship code was allocated.

In nonmetropolitan Alabama, for example, 3.63% worked for NPOs and 72.27%

worked for private firms; I therefore assigned each worker in that area a 3.63%

probability of nonprofit employment and a 72.27% probability of for-profit

employment.

Latino is coded 1 for all those who checked “Spanish/Hispanic/Latino.” The race

variables are coded 1 only if Latino is coded 0. African American is coded 1 for

those who checked only “Black, African American, or Negro” and Asian American is coded 1 for those who checked only one or more of the Asian options. Those

who checked “American Indian or Alaska Native” or multiple races (and were not

Latino) are coded 1 on Other or Mixed Race. The reference group is those who

only checked “White.”

These are calculated as the percentage of private sector employees (dropping the

self-employed and government workers) who worked for NPOs within each metropolitan area, detailed occupation, or detailed industry (separately). Using the full

set of dummy variables was not practical computationally. In one group (male college graduates), the far simpler probability variable contributed almost as strongly

to the McFadden’s pseudo-R2 and did not meaningfully change the Has Same-Sex

Partner coefficient.

Because coupled gay men are more than twice as likely as married men to work

for NPOs, they are actually one half (rather than one fourth) as likely as married

men to work for religious organizations. This also means that they are more than

12 times as likely as married men to work for museums and art galleries.

Occupational choice accounts for some of the difference: Controlling for 25 broad

occupational categories makes the gay–straight pay gaps more similar in the two

sectors.

References

Allegretto, S. A., & Arthur, M. M. (2001). An empirical analysis of homosexual/heterosexual male earnings differentials: Unmarried and unequal? Industrial and

Labor Relations Review, 54, 631-646.

Antonovics, K., & Town, R. (2004). Are all the good men married? Uncovering the

sources of the marital wage premium. American Economic Review, 94, 317-321.

Badgett, M. V. L. (1995). The wage effects of sexual orientation discrimination.

Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 48, 726-739.

Badgett, M. V. L. (2001). Money, myths, and change: The economic lives of lesbians

and gay men. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010

745

Lewis

Badgett, M. V. L., & King, M. C. (1997). Lesbian and gay occupational strategies. In

A. Gluckman & B. Reed (Eds.), Homo economics: Capitalism, community, and

lesbian and gay life (pp. 73-86). New York, NY: Routledge.

Barrett, D. C., Pollack, L. M., & Tilden, M. L. (2002). Teenage sexual orientation,

adult openness, and status attainment in gay males. Sociological Perspectives,

45, 163-182.

Benz, M. (2005). Not for the profit, but for the satisfaction? Evidence on worker wellbeing in non-profit firms. Kyklos, 58, 155-176.

Belman, D., & Heywood, J. S. (1989). Government wage differentials: A sample

selection approach. Applied Economics, 21, 427-439.

Berg, N., & Lien, D. (2002). Measuring the effect of sexual orientation on income:

Evidence of discrimination? Contemporary Economic Policy, 20, 394-414.

Black, D. A., Gates, G., Sanders, S., & Taylor, L. (2007). The measurement of samesex unmarried partner couples in the 2000 U.S. census. California Center for Population Research, University of California–Los Angeles.

Black, D. A., Gates, G., Taylor, L. J., & Sanders, S. G. (2000). Demographics of the

gay and lesbian population in the United States: Evidence from available systematic data sources. Demography, 37, 139-154.

Black, D. A., Gates, G., Taylor, L. J., & Sanders, S. G. (2002). Why do gay men live

in San Francisco? Journal of Urban Economics, 51, 54-76.

Black, D. A., Makar, H. R., Taylor, L. J., & Sanders, S. G. (2003). The effects of sexual orientation on earnings. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 56, 449-469.

Black, D. A., Sanders, S. G., & Taylor, L. J. (2007). The economics of lesbian and gay

families. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(2), 53-70.

Blandford, J. M. (2003). The nexus of sexual orientation and gender in the determination of earnings. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 56, 622-642.

Brooks, A. C. (2006). Who really cares: The surprising truth about compassionate

conservatism: America’s charity divide—Who gives, who doesn’t, and why it matters. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Carpenter, C. (2003). Sexual orientation and body weight: Evidence from multiple

surveys. Gender Issues, 21(3), 60-74.

Carpenter, C. (2004). New evidence on gay and lesbian household incomes. Contemporary Economic Policy, 22, 78-94.

Carpenter, C. (2005). Self-reported sexual orientation and earnings: Evidence from

California. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 58, 258-273.

Carpenter, C., & Gates, G. (2008). Gay and lesbian partnership: Evidence from California. Demography, 45, 573-590.

Clain, S. H., & Leppel, K. (2001). An investigation into sexual orientation discrimination as an explanation for wage differences. Applied Economics, 33, 37-47.

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010

746

Administration & Society 42(6)

Cornwell, C., & Rupert, P. (1997). Unobservable individual effects, marriage and the

earnings of young men. Economic Inquiry, 21, 285-294.

Crewson, P. E. (1997). Public-service motivation: Building empirical evidence of

incidence and effect. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 7,

499-518.

Crow, S. M., Fok, L. Y., & Hartman, S. J. (1998). Who is at greatest risk of workrelated discrimination—Women, Blacks, or homosexuals? Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 11, 15-26.

Egan, P. J. (2009, March). Group cohesion without group mobilization: The case of

lesbians, gays, and bisexuals (Working Paper). Retrieved from http://politics.

as.nyu.edu/docs/IO/4819/cohesionwomobilization.pdf

Egan, P. J., & Sherrill, K. (2005). Neither an in-law nor an outlaw be: Trends in Americans’ attitudes toward gay people. Public Opinion Pros (February). Retrieved

from http://www.publicopinionpros.com/

Frank, R. H. (1996). What price the moral high ground? Southern Economic Journal,

63(1), 1-17.

Gates, G. J., & Ost, J. (2004). The gay and lesbian atlas. Washington, DC: Urban

Institute.

Ginther, D. K., & Zavodny, M. (2001). Is the marriage premium due to selection?

The effects of shotgun weddings on the return to marriage. Journal of Population

Economics, 14, 313-328.

Goddeeris, J. H. (1988). Compensating differentials and self-selection: An application

to lawyers. Journal of Political Economy, 96, 411-428.

Gray, J. (1997). The fall in men’s return to marriage: Declining productivity effects or

changing selection? Journal of Human Resources, 32, 481-504.

Gyourko, J., & Tracy, J. (1988). An analysis of public- and private-sector wages

allowing for endogenous choices of both government and union status. Journal of

Labor Economics, 6, 229-253.

Hansmann, H. B. (1980). The role of nonprofit enterprise. Yale Law Journal, 89, 835-901.

Hebl, M. R., Foster, J. B., Mannix, L. M., & Dovidio, J. F. (2002). Formal and interpersonal discrimination: A field study of bias toward homosexual applicants. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 815-825.

Irons, J. S., & Bass, G. (2004). Recent trends in nonprofit employment and earnings:

1990-2004 Tax and Budget Reports. Washington, DC: OMB Watch.

Jeavons, T. H. (1992). When the management is the message: Relating values to management practice in nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 2, 403-417.

Jepsen, L. K. (2007). Comparing the earnings of cohabiting lesbians, cohabiting heterosexual women, and married women: Evidence from the 2000 Census. Industrial Relations, 46, 699-727.

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010

747

Lewis

Johnson, D. K. (2004). The lavender scare: The Cold War persecution of gays and

lesbians in the federal government. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Karl, K. A., & Sutton, C. L. (1998). Job values in today’s workforce: A comparison of

public and private sector employees. Public Personnel Management, 27, 515-516.

Klawitter, M. M., & Flatt, V. (1998). The effects of state and local antidiscrimination policies for sexual orientation. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 17, 658-686.

Korenmann, S., & Neumark, D. (1991). Does marriage really make men more productive? Journal of Human Resources, 26, 282-307.

Krashnisky, H. A. (2004). Do marital status and computer usage really change the

wage structure? Journal of Human Resources, 39, 774-791.

Leete, L. (2000). Wage equity and employee motivation in nonprofit and for-profit

organizations. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 43, 423-446.

Leete, L. (2001). Whither the nonprofit wage differential? Estimates from the 1990

Census. Journal of Labor Economics, 19, 136-170.

Lewis, G. B. (1997). Lifting the ban on gays in the civil service: Federal policy toward

gay and lesbian employees since the Cold War. Public Administration Review, 57,

387-395.

Lewis, G. B. (2006). The demographics of Georgia I: lesbian and gay couples. (FRC

Brief 113): Fiscal Research Center, Andrew Young School of Policy Studies,

Georgia State University.

Lewis, G. B., & Frank, S. A. (2002). Who wants to work for the government? Public

Administration Review, 62, 395-404.

Lewis, G. B., & Pitts, D. W. (2010). Representation of lesbians and gay men in federal, state, and local bureaucracies. Journal of Public Administration Research

and Theory, in press.

Lewis, G. B., Rogers, M. A., & Sherrill, K. (2003, May). Sexual identity, sexual

behavior, and group socialization: Does gay sex turn people into liberal democrats? Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for

Public Opinion Research, Nashville, TN.

Light, P. C. (2002). Pathways to nonprofit excellence. Washington, DC: Brookings

Institution.

Loh, E. S. (1996). Productivity differences and the marriage wage premium for White

males. Journal of Human Resources, 31, 568-589.

Long, J. S., & Freese, J. (2006). Regression models for categorical dependent variables using Stata (3rd ed.). College Station, TX: Stata Press.

Mirvis, P. H. (1992). The quality of employment in the nonprofit sector: An update

on employee attitudes in nonprofits versus business and government. Nonprofit

Management and Leadership, 3, 23-41.

Mirvis, P. H., & Hackett, E. J. (1983). Work and work force characteristics in the

nonprofit sector. Monthly Labor Review, 106(4), 3-12.

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010

748

Administration & Society 42(6)

Moulton, B. R. (1990). A reexamination of the federal–private wage differential in the

United States. Journal of Labor Economics, 8, 270-293.

Onyx, J., & Maclean, M. (1996). Careers in the third sector. Nonprofit Management

and Leadership, 6, 331-345.

Perry, J. L., & Wise, L. R. (1990). The motivational bases of public service. Public

Administration Review, 50, 367-373.

Preston, A. E. (1989). The nonprofit worker in a for-profit world. Journal of Labor

Economics, 7, 438-463.

Preston, A. E. (1990). Women in the white-collar nonprofit sector: The best option or

the only option? Review of Economics and Statistics, 72, 560-568.

Rainey, H. G. (1982). Reward preferences among public and private managers: In

search of the service ethic. The American Review of Public Administration, 16,

288-302.

Rose-Ackerman, S. (1996). Altruism, nonprofits, and economic theory. Journal of

Economic Literature, 34, 701-728.

Ruhm, C. J., & Borkowski, C. (2003). Compensation in the nonprofit sector. Journal

of Human Resources, 38, 992-1021.

Salamon, L. M., & Sokolowski, S. W. (2006). Employment in America’s charities: A

profile. Nonprofit Employment Bulletin.

Smith, S. P. (1976). Government wage differentials by sex. Journal of Human

Resources, 11, 185-199.

Stratton, L. (2002). Examining the wage differential for married and cohabiting men.

Economic Inquiry, 49, 199-212.

Washington Post, Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, & Harvard University. (1998).

Survey on American Values. (2,025 telephone interviews conducted July 29 - August

18, 1998).

Weichselbaumer, D. (2003). Sexual orientation discrimination in hiring. Labour Economics, 10, 629-642.

Weisbrod, B. A. (1983). Nonprofit and proprietary sector behavior: Wage differentials

among lawyers. Journal of Labor Economics, 1, 246-263.

Wittmer, D. (1991). Serving the people or serving for pay: Reward preferences among

government, hybrid sector, and business managers. Public Productivity & Management Review, 14, 369-383.

Bio

Gregory B. Lewis is professor of public management and policy in the Andrew

Young School of Policy Studies at Georgia State University and director of the joint

Georgia State-Georgia Tech doctoral program in public policy. He has published

widely on the career patterns and attitudes of public employees, on public support for

lesbian and gay rights, and on morality policy more broadly.

Downloaded from aas.sagepub.com at CAL STATE UNIV SACRAMENTO on September 13, 2010