Montana nurse practitioners : prescriptive authority by Keven Jean Comer

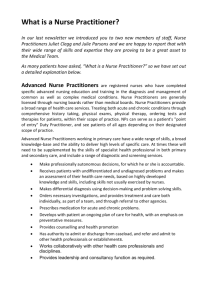

advertisement