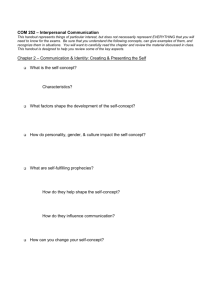

The effects of a cardiac pacemaker on the self-concept of... self-concept scale

advertisement