The Burden of Corporate Probation May Follow an Antitrust Conviction

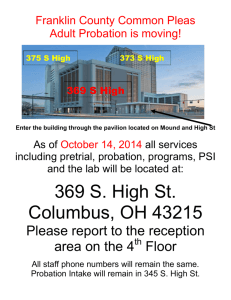

advertisement

September 22, 2014 Practice Groups: The Burden of Corporate Probation May Follow an Antitrust Conviction Antitrust, Competition & Trade Regulation; U.S. Antitrust, Competition & Trade Regulation Alert Corporate/M&A; The Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice (the “Division”) has announced a major policy shift. When a company has been convicted for a criminal antitrust offense, the Division may seek to impose the significant burdens of corporate probation in addition to enormous monetary fines and incarceration for senior executives. Once again, the penalties for antitrust violations will be increased. Government Enforcement; Global Government Solutions By: Steven M. Kowal and Lauren N. Norris In recent speeches by two senior Division officials, the government stated that it will seek court-supervised probation when a convicted company does not have an effective internal compliance program to detect and prevent violations. Moreover, the company’s compliance culture may be deemed ineffective if the company continues to employ individuals who violated the law but did not accept responsibility. In that situation, the Division will contend that the compliance program lacks credibility and probation is “necessary to ensure an effective compliance program and to prevent recidivism.” Prior to the issuance of these statements, the Division seldom sought corporate probation and did not express a position concerning the retention of potentially culpable employees. Corporate Probation under United States Sentencing Guidelines Criminal antitrust offenses already are punished severely. Companies often pay monetary fines of a $100 million or more, and executives are often imprisoned for significant periods. In addition to these penalties, courts also are authorized to impose probation on the company. The United States Sentencing Guidelines governing the Sentencing of Organizations (the “Sentencing Guidelines”) control the determination of the penalty for the company. The Sentencing Guidelines address, among other things, when a term of probation is required, the length of the probationary period and the conditions that must be met. Among other reasons, probation is required if (a) the organization has 50 or more employees or was otherwise required by law to have an effective compliance program and the organization did not have such a program1 or (b) probation is necessary to ensure that changes are made within the organization to reduce the likelihood of future criminal conduct.2 When a sentence of probation is imposed for an antitrust violation, the term of probation is between one and five years.3 Of course, the company will be prohibited from committing any federal, state or local offenses during the probationary term. Also, the court can impose a series of requirements including publicizing the nature of the offense, developing an internal compliance and ethics program, notifying the company’s employees and shareholders of the compliance and ethics program, making periodic reports to the court including disclosure of financial condition and material adverse financial changes, and submitting to regular or The Burden of Corporate Probation May Follow an Antitrust Conviction unannounced examinations of books and records. Clearly, these conditions can be onerous and intrusive. Significantly, the court is authorized to appoint an independent monitor to review the company’s compliance with the probationary terms and to ensure that an effective compliance program is developed and fully implemented. The corporate monitor will be invested with broad authority within the company, and will be required to report periodically directly to the court and the Division. Thus, the monitor will have significant responsibility that supersedes the company’s management, and the cost of the monitoring operation and review can be substantial. Recent Policy Shift by the Antitrust Division On September 10, William Baer, the Division’s Assistant Attorney General, addressed Georgetown University Law Center’s Global Antitrust Enforcement Symposium. His speech, entitled “Prosecuting Antitrust Crimes,” focused on criminal enforcement and the Division’s approach to companies and executives that commit antitrust offenses. He summarized the Division’s leniency program and discussed its application to both corporations and individuals. He also highlighted the importance of corporate compliance programs, emphasizing the need for corporations to take compliance seriously, and underlining the potential benefits. He asserted that, “[e]ffective compliance programs minimize the chance that companies will conspire to fix prices [a]nd they maximize the chance for a company guilty of price fixing to find out about the conspiracy early enough to qualify for corporate leniency or otherwise cooperate with [the Division’s] investigation.” Mr. Baer emphasized the Division’s expectation that companies that have pled guilty to or been convicted of antitrust violations take compliance seriously, explaining that this requires “an institutional commitment to change the culture of the company.” In this context, he discussed the tension that is created when a guilty company argues that its compliance program is effective while at the same time continuing to employ culpable senior executives who did not accept responsibility. As he explained, “[i]t is hard to imagine how companies can foster a corporate culture of compliance if they still employ individuals in positions with senior management and pricing responsibilities who have refused to accept responsibility for their crimes and who the companies know to be culpable.” He then articulated the Division’s policy for this situation: If any company continues to employ such individuals in positions of substantial authority; or in positions where they can continue to engage directly or indirectly in collusive conduct, or in positions where they supervise the company’s compliance and remediation programs, or in positions where they supervise individuals who would be witnesses against them, we will have serious doubts about that company’s commitment to implementing a new compliance program or invigorating an existing one. Indeed, the Sentencing Guidelines go so far as to suggest that companies that do so cannot be said to have an “effective” compliance program. In such cases, the division will consider seeking court-supervised probation as a means of assuring that the company devises and implements an effective compliance program. We reserve the right to insist on probation, including the use of monitors, if doing so is necessary to ensure an effective compliance program and to prevent recidivism.4 2 The Burden of Corporate Probation May Follow an Antitrust Conviction On September 9, 2014, Brent Snyder, the Division’s Deputy Assistant Attorney General for Criminal Enforcement, emphasized these same issues in a speech delivered to the International Chamber of Commerce and United States Council of International Business’ Joint Antitrust Compliance Workshop. During his speech, appropriately entitled, “Compliance is a Culture, Not Just a Policy,” Mr. Snyder discussed corporate compliance programs and their importance in preventing and detecting illegal conduct. He explained that a “truly wellrun compliance program should prevent a company from conspiring to fix prices, rig bids, or allocate markets…or, at a minimum, detect it and stop it shortly after it starts.” Although achieving the former is obviously preferable, he explained that the latter may allow a company to self-report its conduct under the Division’s Corporate Leniency Program, an action that requires a time and financial commitment to cooperating with the investigation, but allows the company to avoid criminal prosecution. Although cautioning that compliance programs should be uniquely tailored to the industry and markets in which a company operates, Mr. Snyder identified the following hallmarks of effective compliance programs: (1) active support from senior management; (2) education and training for all executives and managers, as well as employees with sales and pricing responsibilities; (3) an anonymous reporting system that allows employees to report and/or seek guidance about potential or actual criminal violations without fear of retaliation; (4) proactive monitoring of at-risk activities; (5) regular review and evaluation of the compliance program; and (6) disciplinary action for employees who engage in criminal conduct. Regarding the last point, he cautioned that “[a] company’s retention of culpable employees in positions where they can repeat that conduct, impede a company’s internal investigation and cooperation, or influence employees who may be called upon to testify against them, raises serious questions and concerns about the company’s commitment to effective antitrust compliance.” Mr. Snyder warned that the mere existence of a compliance program will not result in a company’s avoiding criminal antitrust charges and that the Division will not necessarily recommend that companies receive credit at sentencing simply for having a preexisting compliance program. He stated, however, that companies that can show they adopted or strengthened existing compliance programs may avoid probation. He also explained that the Division is “actively considering ways in which [it] can credit companies that proactively adopt or strengthen compliance programs after coming under investigation,” and although the Division’s policy is not finalized, “any crediting of compliance will require a company to demonstrate that its program or improvements are more than just a façade.”5 Practical Guidance Best practices have always dictated that a company should establish, implement, and regularly review and update a compliance program. This is especially true in the current enforcement environment. The risk of detection and punishment is significant, and dozens of countries are aggressively pursuing cartel enforcement and working together to detect and 3 The Burden of Corporate Probation May Follow an Antitrust Conviction punish cartel activity. All companies should review their compliance programs and ensure that they contain the following elements, at a minimum: (1) Active support from the company’s senior executives and board of directors. Senior management should be fully knowledgeable about the organization’s compliance efforts, provide the necessary resources and assign the right people to oversee those efforts, and ensure that the program is successfully implemented and monitored. (2) An education and training program for all executives and managers, as well as employees with sales and pricing responsibilities. (3) An anonymous reporting system that allows all members of the organization to report and/or seek guidance about potential or actual criminal violations without fear of retaliation. (4) Proactive monitoring of any at-risk activities, such as joint ventures with competitors or industry meetings. This may include the presence of antitrust counsel at meetings where competitors will be present or the performance of regular antitrust audits. (5) Regular review and evaluation of the company’s compliance program. (6) Disciplinary action for employees who engage in illegal conduct. Companies that come under investigation for antitrust violations will be best served by taking a hard look at their preexisting compliance programs. Once misconduct is discovered, even if it is not yet disclosed to an enforcement authority, the company should take proactive steps to strengthen and improve its compliance program and should carefully consider how it disciplines culpable individuals. Antitrust counsel should be consulted and all actions taken by the company should be well documented. Should the company eventually be charged, these proactive measures can help avoid the burdens of corporate probation. Authors: Steven M. Kowal steven.kowal@klgates.com +1.312.807.4430 Lauren N. Norris lauren.norris@klgates.com +1.312.807.4218 4 The Burden of Corporate Probation May Follow an Antitrust Conviction Anchorage Austin Beijing Berlin Boston Brisbane Brussels Charleston Charlotte Chicago Dallas Doha Dubai Fort Worth Frankfurt Harrisburg Hong Kong Houston London Los Angeles Melbourne Miami Milan Moscow Newark New York Orange County Palo Alto Paris Perth Pittsburgh Portland Raleigh Research Triangle Park San Francisco São Paulo Seattle Seoul Shanghai Singapore Spokane Sydney Taipei Tokyo Warsaw Washington, D.C. Wilmington K&L Gates comprises more than 2,000 lawyers globally who practice in fully integrated offices located on five continents. The firm represents leading multinational corporations, growth and middle-market companies, capital markets participants and entrepreneurs in every major industry group as well as public sector entities, educational institutions, philanthropic organizations and individuals. For more information about K&L Gates or its locations, practices and registrations, visit www.klgates.com. This publication is for informational purposes and does not contain or convey legal advice. The information herein should not be used or relied upon in regard to any particular facts or circumstances without first consulting a lawyer. © 2014 K&L Gates LLP. All Rights Reserved. 1 USSC Guidelines Manual, Section 8D.1.1(a)(3). USSC Guidelines Manual, Section 8D.1.1(a)(6). 3 USSC Guidelines Manual, Section 8D.1.2. 4 Mr. Baer’s speech can be accessed at: http://www.justice.gov/atr/public/speeches/308499.pdf 5 Mr. Snyder’s speech can be accessed at: http://www.justice.gov/atr/public/speeches/308494.pdf 2 5