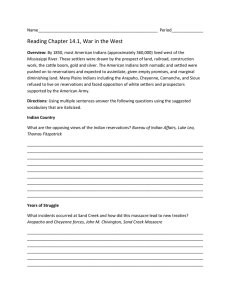

Integration of the Montana Indian into the state of Montana... by Gary Melvin Small

advertisement