Prediction of available forage production of big sagebrush

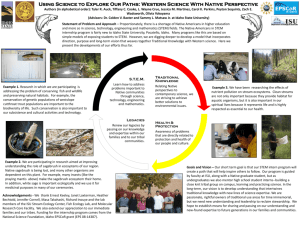

advertisement