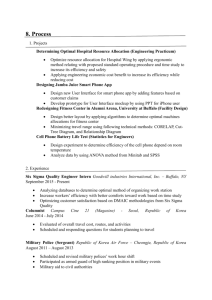

REPUBLIC OF KOREA

advertisement