Document 13507760

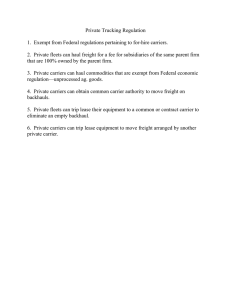

advertisement