Litigation Session

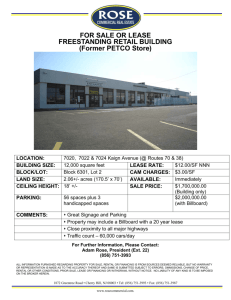

advertisement