Qualitative comparison of basic movement patterns of preschool age children

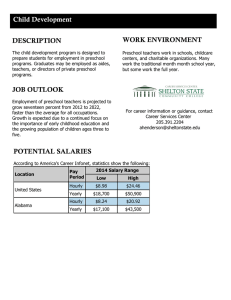

advertisement