A recommended art program for the elementary schools of Livingston,... by Walter F Lab

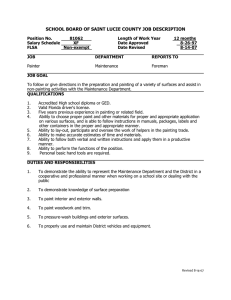

advertisement