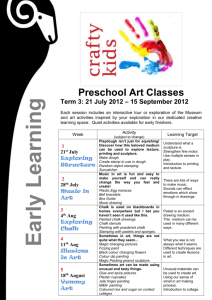

A proposed plan for instrumenting a child centered art program... by Helen Autry Conrad

advertisement