Miners, managers, and machines : industrial accidents and occupational disease... underground, 1880-1920

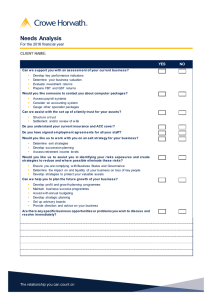

advertisement

Miners, managers, and machines : industrial accidents and occupational disease in the Butte

underground, 1880-1920

by Brian Lee Shovers

A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History

Montana State University

© Copyright by Brian Lee Shovers (1987)

Abstract:

Between 1880 and 1920 Butte, Montana achieved world-class mining status for its copper production.

At the same time, thousands of men succumbed to industrial accidents and contracted occupational

disease in the Butte underground, making Butte mining significantly more dangerous than other

industrial occupations of that era. Three major factors affected working conditions and worker safety in

Butte: new mining technologies, corporate management, and worker attitude.

The introduction of new mining technologies and corporate mine ownership after 1900 combined to

create a sometimes dangerous dynamic between the miner and the work place in Butte. While

technological advances in hoisting, tramming, lighting and ventilation generally improved underground

working conditions, other technological adaptations such as the machine drill, increased the hazard of

respiratory disease. In the end, the operational efficiencies associated with the new technologies could

not alleviate the difficult problems of managing and supervising a highly independent, transient, and

often inexperienced work force.

With the beginning of the twentieth century and the consolidation of most of the major Butte mines

under the corporate entity of Amalgamated Copper Company (later the Anaconda Copper Mining

Company), conflict between worker and management above ground increased. At issue were wages,

conditions, and a corporate reluctance to accept responsibility for occupational hazards. The new

atmosphere of mistrust between miners and their supervisors provoked a defiant attitude towards the

work place by workers which increased the potential for industrial accidents.

Eforts by organized labor to improve underground conditions in Butte through protective legislation,

compensation for work-related accidents and disabilities, and through work stoppages, failed to halt

industrial accidents or to effectively alter a recalcitrant disregard held by miners for the dangers of the

work place, created over a forty year period in which thousands of Butte miners lost their lives on the

job.

This study consists of six chapters: Chapter One is an introduction; Chapter Two offers a profile of the

miner's life above and below ground; Chapter Three examines the impact of new mining technologies

on the dynamics of the work place; Chapter Four explores the high incidence of accidental fatalities

and occupational health hazards in the Butte underground; Chapter Five documents the miners struggle

to improve working conditions; and Chapter Six is a conclusion. MINERS, MANAGERS, AND MACHINES: INDUSTRIAL ACCIDENTS

AND OCCUPATIONAL DISEASE IN THE BUTTE UNDERGROUND,

1880-1920

by

Brian Lee Shovers

1 - ,

: ■•

'

A thesis sub m itted in p a rtial fulfillm ent

of th e re q u ire m e n ts for th e degree

of

M aster of A rts

in

History

MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY

Bozeman, M ontana

A pril 1987

Archives

Sh^ S3

Cop. I

I,

APPROVAL

of a thesis subm itted by

Brian Lee Shovers

This thesis has b een re a d b y each m em ber of th e th esis com m ittee

and has b een found to b e satisfactory regarding content, English usage,

fo rm at, citations, bibliographic style, and consistency, and is rea d y for

subm ission to th e College of G raduate Studies.

Siicf /y, /<ry

Date

Chairperson, G raduate Com mittee

A pproved for th e D epartm ent of H istory & Philosophy

'4 ^ 7 /7

Bate

/? ? ?

Head, D e p a rtm ^ n w r^ M o ry

A pproved for th e College of G raduate Studies

Date

Graduate Dean

Ill

STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO USE

In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillm ent of th e req u ire m e n ts for

a m aster's degree a t M ontana State U niversity, I agree th a t th e L ib rary shall

m ake it available to b o rrow ers u n d er ru les of th e L ibrary. Brief quotations

from th is thesis a re allow able w ith o u t special perm ission, provided th a t

accurate acknow ledgem ent of source is made.

Perm ission for extensive quotation from or reproduction of th is thesis

m ay b e g ran ted b y m y m ajor professor, or in h is /h e r absence, b y th e

Director of th e L ibraries w hen, in th e opinion of e ith er, th e proposed use of

th e m aterial is for scholarly purposes. Any copying or use of th e m aterial in

th is thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed w ith o u t m y w ritte n

perm ission.

Signature

D a te ____

Iv

.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This th esis could n o t h av e b een com pleted w ith o u t th e guidance

and assistance of th re e individuals. Paula P etrik, m y p rim a ry thesis

advisor d eserv es cred it for steering m e tow ards m y chosen topic and

for providing focus to m y research and encouragem ent to me

throughout. I am also in d eb ted to Robert Rydell for his insightful

criticism and enth u siasm for m y topic from th e outset. Finally j

w ould like to th an k T eresa Jo rd an for h e r helpful critiques of m y

p a p er from s ta rt to finish.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

LIST OF TABLES............ .............................................................................................. v i

ABSTRACT....................................................................................................................... vii

CHAPTER

1.

In tro d u c tio n ................

I

2. Life Above and Below Ground on th e In d u strial F rontier.................. 11

3. New Technologies And The Dynamics Of The W ork P la c e ................ 29

4. The High Cost Of Mining: U nderground Fatalities And Occupational

Health H azards................................................................................................ 63

5. The Struggle To Im prove U nderground W orking Conditions........... 85

6. C onclusion...................................................................................................... 113

BIBLIOGRAPHY............... ......................... ;............................................. ...................j 19

vi

LIST OF TABLES'

Page

TABLE I: Causes of B utte Mine Fatalities.................... ‘......................................... 57

TABLE 2: Correlation Betw een Price, Productivity, N um ber of W orkers,

And The F atality Rate For Butte, M ontana.......... ............................. 55

ABSTRACT

diffieull problem s of m anaging and supervising a highly '

in d ep en d ent, tran sie n t, and o ften inexperienced w ork force.

mn<!t J tlE

?f lh e tw e n tie th c e n tu ry and th e consolidation of

e m a) or, P u tte p m e s u n d er th e corporate e n tity of A m algam ated

Copper Company (later th e Anaconda Copper Mining Company), conflict

J etJ een wSFjFe r and m anagem ent above ground increased. At issue w e re

th e ir su p ervisors provoked a d efian t a ttitu d e tow ards th e w ork place by

w o rk ers w hich increased th e potential for in d u strial accidents

organized labor to im prove underground conditions in Butte

p ro te^ 1Xf leS1Slation, com pensation for w o rk -re la te d accidents and

eSB SSse-ssa

■M BE

I

Chapter I

INTRODUCTION

On May 1 5 ,1 9 1 7 , a coroner's ju ry convened in Butte, M ontana to

in v estig ate th e accidental d e ath of m iner Charles Borlace. Borlace a

th irty -eig h t-y ea r-o ld Cornishm an from Michigan, died in th e Alice Mine

w h en th e cage he w as riding plum m eted tw o h u n d red fe e t to th e bottom of

th e shaft. The bolt connecting th e engine brak e to th e cable drum snapped,

and th e safety devices designed to catch a ru n aw ay cage also failed. During

th e inquest, th e hoist engineer. John Davis, testified th a t e v e ry precaution

had been tak e n to p re v e n t such an accident. Ju st th a t m orning, th e

m achinist, John Campbell, had inspected th e hoisting engine and bolts for

defects. W hen questioned fu rth e r, how ever, th e engineer rev ealed th a t th e

accident m ight n e v e r h av e happ en ed had he followed norm al practices,

brought th e cage in th e adjacent shaft to a com plete stop, and engaged th e

clutch. Yet, th e coroner's ju ry exonerated both th e hoist engineer and the

mining com pany of all blam e for Borlace's death, a v erd ict re p e a te d in

v irtu ally e v e ry fatal mining accident investigated in th e copper mining

district of Butte. M ontana b etw een 1880 and 1920.1

The circum stances surrounding th is case and th e m ore th a n one

thousand o th er fatal mine accidents th a t occurred during this period w ere

m uch m ore complex th a n this coroner's ju ry suggested. They raise

im p o rtan t questions about th e effect of th e industrial mining process on th e

w orker. A sim plistic analysis of Borlace s d eath could lead to an indictm ent

2

of now

Qiinuig technologies,

for m achines—the hoist and safety devices—had

failed. But technology cannot be e v alu ated outside of th e social context in

w hich it w as used. The hoisting device th a t failed Charles Borlace w as p a rt

of a m uch larger process th a t encom passed a politically and economically

pow erful corporation, a p re-in d u strial im m igrant culture, fra te rn a l

associations, and labor unions. The conflict in th e B utte underground among

th ese v arious forces and its im pact on w orking conditions is th e subject of

this stu d y .2

My purpose is to focus on th e dangers w ith in th e B utte underground, a

subject th u s fa r only m entioned parenthetically by o th er mining historians.

T here a re excellent stu d ies of th e struggle for corporate control over Butte

m inerals and on th e evolution of organized labor and radical politics in Butte,

b u t none of th ese a tte m p t to explain th e social and econom ic forces linking

life above ground w ith th e dangers below ground. My stu d y poses th e

hypothesis th a t th e causes of hazardous w orking conditions and in dustrial

accidents cannot be e v alu ated w ith o u t paying a tten tio n to technological

advances in th e mining process, as w ell as political and econom ic

relationships at w ork in th e com m unity at large. The high n u m b er of w o rk er

fatalities th a t occurred in th e B utte m ines resu lte d from a complex set of

technological, economic, environm ental and social circum stances.

Interactions b etw een u n derground m iners and m anagers m irrored the

political cu lture found above ground, often to th e d e trim e n t of th e h ealth

and safety of th e w ork force.

Hardrock mining had alw ays b een a dangerous occupation, fra u g h t

w ith hazards unim agined b y th e w o rk e r above ground, b u t b etw een 1880

3

and 1920 an alarm ing n u m b er of m en died in in d u strial accidents and of

occupational diseases in th e copper m ines of Butte. B utte ran k e d as one of

th e m ost dangerous mining districts in th e w orld, w ith a fatal accident ra te

th re e tim es higher th a n trad itio n al mining districts in Cornwall. The danger

w as directly re la te d to th e large scale mining operation developed in B utte in

th e late n in etee n th and early tw e n tieth centuries. The story of large scale

copper mining in B utte actually begins before 1883 on th e east coast.

The chronology actually sta rts in 1876, thousands of miles from Butte

in Philadelphia, w ith A lexander Graham Bell’s dem onstration of th e

telephone at th e C entennial Exhibition. Bell's new invention req u ire d

copper, as did Thom as Edison's incandescent light bulb, p aten ted in 1880.

These tw o technological advances, along w ith expanded in d u strial and

resid en tial use of electricity, created enorm ous dem and for copper in th e last

tw o decades of th e n in etee n th century.

A se t of fo rtu ito u s geologic, technologic, and econom ic circum stances

coalesced in B utte to cre ate an in d u stry capable of satisfying th is new

dem and. In 1883 M arcus Daly hoisted his first bu ck et of copper ore from

th e Anaconda Mine, w hich w ould u ltim ately becom e one of th e w orld's

rich est copper mines. Copper cannot be m ined and processed w ith o u t a

su b stan tial in v estm en t of capital, w hich M arcus Daly g u a ra n tee d for Butte

w ith th e creation of th e Hearst, Haggin and Tevis Syndicate in 1882. This

v e n tu re ev en tu ally led to th e first in teg rated copper com pany in America.

In 1881 th e U tah and N orthern Railroad arriv ed to c a rry ore for processing

and sale. By 1887, only fo u r y e a rs afte r M arcus Daly began producing ore

from his Anaconda Mine, his corporation led th e w orld in copper production.

4

Sm elting and refining proved another major h u rd le w hich Daly handily

overcam e in 1891 w ith th e construction of th e first electrolytic r e f i n e r y - it

used an electrical process to rem ove all im purities from co p p er— in th e

West, tw e n ty -s ii m iles from Butte, in Anaconda. William A. Q ark and F.

A ugustus Hemze both ow ned im p o rtan t Butte mining in te re sts and rem ained

agressive com petitors of Daly's. Heinze personally w aged an unsuccessful

w a r against consolidation efforts by A m algam ated Copper, a precursor to

ACM and th e in h erito r of Daly's m ineral properties. By 1910, New York and

Boston in vestors consolidated th e individual e n tre p re n e u ria l efforts of Daly,

Clark and Heinze into a m assive corporate e n te rp rise to becom e know n as

th e Anaconda Copper Mining Com pany (ACM). The Anaconda Company

continued to dom inate w orld copper production fo r th e next th irty years.

affecting th e in te rp la y b etw een technology and safety w ith in th e Butte

underground.^

The pow er of mining corporations like th e A naconda Company is not

new to historians, b u t contem porary mining histories hav e m ost often

focused on details of mining cam p life, corporate m aneuvering w ithin th e

in d u stry , descriptions of th e m achinery and processes necessary to extract

m etals, and th e politics of organized labor w ithout paying adequate atten tio n

to th e in teraction of people and th e in d u strial process. Only a sm all group of

historians, led m ost recen tly b y M erritt Roe Smith. Ronald C. Brown, and

M ark W yman, have closely exam ined th e im pact of technological change on

th e w orker. In

Harper's F errv

A rm orv a n d th e N ev Technology Th*

Challenge Of Change. Sm ith explored

th e im pact of w o rk er resistance to

technological changes in A m erica's early arm am ents in d u stry . Brown and

Wyman's books marked a departure from earlier historical studies of the

mining West in that they focused more directly on the impact of industrial

technologies on miners' lives. Although Brown and Wyman both focused on

occupational hazards of the work place, they arrived at very different

assessments of technological innovations. In Hard-Rnck Miners: Thg

Intgrmpvmtain West. 1860-1920, which ignores Butte mining, Brown

carefully documented the life of the industrial work force and concluded that

new mining technologies ultimately made the work place safer and the work

more dependable for the worker. Wyman, on the other hand, in Hard Rock

Epic; Wgstgrn Miners and the Industrial Revolution. I86n-iQjp indicted

both new technologies for creating unforseen hazards underground and mine

owners for failing to accept responsibility for company negligence, citing

specific examples of unsafe conditions and accidents in Butte associated with

new mining techniques. The work of both Brown and Wyman prompted

consideration of some broader questions regarding the relationship between

new mining technologies and worker safety.^

This stu d y of th e B utte m iner and w orking conditions draw s together

several historiographic trad itio n s — th e h isto ry of technology, th e history of

mining in th e W est, and th e h isto ry of business and labor.

My stu d y of

Butte, following Sm ith’s lead, focuses on th e w o rk ers them selves — on how

particular technological innovations affected them and how th e y responded

to new h azards in th e w ork place. W hat I contribute in this approach is th e

use of new source m aterials, as w ell as a fresh in te rp re ta tio n of Butte

mining. No one has looked at th e coroner's in q u est prior to m y research as a

source of inform ation about relationships betw een m iners and supervisors.

6

about th e liabilities in h e re n t in new mining technologies, and about w o rk er

h ab its and attitudes. Evidence of th ese relationships em erges, in part, from

th e voices of m iners and th e ir supervisors recorded in a sam ple of o ver tw o

h u n d red surviving coroner's inquests. This testim ony rev eals th e co m p leiity

of circum stances associated w ith in d u strial mine accidents; th e corporate

dom ination of w o rk ers on th e job and w ithin th e society at large; and th e

im portance of com m unication betw een w o rk ers and m anagem ent. While the

in q u est provided an unusual o p p o rtu n ity to h e ar m iners talk about th eir

w ork, th e facts regarding m anagem ent's com plicity in fa ta l m ine accidents

often rem ained unspoken because of fe a r of reprisal. W itnesses to fata l

accidents testified in th e presence of com pany supervisors during coroner's

inquests, leaving them v u ln erab le to blacklisting and intim idation for

speaking out against com pany negligence, a v e ry real possibility in a city

w h e re a single corporation dom inated th e mining economy. Coroner's

inquests, in short, w ere h a rd ly v a lu e -fre e ." N evertheless, th e y unveil th e

conditions under w hich m iners labored in Butte during th e early p a rt of th e

tw e n tieth cen tu ry and illum inate th e political and econom ic hegem ony

m aintained b y th e A naconda Company over its em ployees.

My stu d y builds on tw o o th er scholarly stu d ies w hich focused on the

social im plications of technological change in th e mining in d u stry .

In

"Im m igrant W orkers and In d u strial Hazards: The Irish M iners of Butte.

1880-1919." h istorian David Emmons described th e e x te n t of industrial

hazards fo r Irish m iners in B utte and th e ir collective resp o n se through

fra te rn a l associations. Emmons concluded th a t th is unified cultural response

helped th e Irish cope w ith th e ir hazardous jobs.

In "Technological

7

Advances, Organizational S tructure, and U nderground Mining Fatalities in the

U pper Michigan Copper Mines, 1860-1929," Michigan scholars L arry Lankton

and Jack M artin used d ata docum enting th e cause of m ine accidents in

Calumet, Michigan to ev alu ate th e im pact of technology on w o rk er safety.

They concluded th a t th e ex trao rd in ary increase in fatalities during this

period w as due to in d u strial expansion and an increase in th e size of th e

w ork force, and th a t th e larger, m ore technologically sophisticated operations

w e re generally safer th a n th e m ore prim itive, sm aller m ines 5

My d ata

from B utte suggests a differen t conclusion, how ever. If th e y e a rs betw een

1915 and 1917 are any indication, it show ed th e sm aller B utte m ines

achieved safer w orking conditions and a low er fata l accident ra te th a n th e

larg er operations.^

Scholarly stu d y of in d u strial hardrock mining is a relativ ely recen t

phenom enon in th e historiography of th e Am erican W est. Although mining

has rep re se n te d a m ajor w e ste rn in d u stry since th e 1860s. historians have

typically em phasized th e rom antic e ra of th e California gold ru sh or labor

violence in Colorado, Idaho and M ontana during th e e a rly p a rt of th e

tw e n tieth cen tu ry . A d ifferen t approach began to characterize th e subject

in i 950 w ith histo rian V ernon Jensen's. Heritage of Conflict- Tahnr

i a th e

Nonferrous M etals

In d u stry Uo to i< n o

Jensen described conflict

b etw een labor and m anagem ent in th e copper and silver in d u stry — paying

particular atten tio n to th e evolution and dem ise of organized labor in Butte

— as a consequence of p articular economic, social, political, psychological and

geographical forces. Accw ding to Jensen, these conflicts o ver issues of

p ro p erty v e rsu s hu m an rig h ts b etw een m anagers and m iners rem ained

8

unresolved. Two overview s of th e gold and silver mining fro n tie r followed

in 1963: The Bonanza W est. 1848-1900 bv Wiliam Greever, and Mining

Frontiers of th e Far W est. 1848-1880 by Rodman Paul. G reever describes

th e progressive advance of th e mining fro n tier culm inating in th e A laskan

gold ru sh . Paul docum ents th e interrelatio n sh ip among w idely divergent

mining fro ntiers, linked to g eth er by elaborate tran sp o rta tio n system s and by

m iners w ho carried new technologies from place to place and adapted

e iistin g m ethods to new circum stances. Otis Young, Jr. describes th e

estab lish m en t of an A m erican mining trad itio n in his tw o books, W estern

Mining, (1970), and Black Pow der and Hand Steel. (1976)

In both w orks.

Young offers elab o rate descriptions of gold and silver mining techniques,

tools, and th e ir origins. H istorian Richard Lingenfelter, in his 1974 study.

The Hardrock M iners; A H istory of th e Mining Labor M ovem ent in the

Am erican W est. 1863 -1 8 9 3 . argued th a t m ilitant labor unions w ere a

n ecessary response to in d u stria l mining and th a t m ost labor relations during

th is period rem ain ed peaceful, and th a t violent labor strife has been

exaggerated.^

The w o rk of th e se five prom inent mining historians provided

my d e p a rtu re point for exam ining th e technological and social forces

im pinging on th e B utte m iner b e tw een 1883 and 1920.

The political and econom ic forces th a t affected those w orking in th e

Butte m ines is th e subject of tw o rec en t books, The Battle for Butte- Mining

and Politics on th e N orthern Frontier. 1864-1906 b y Mirhaml Mainnm and

Copper Mining and M anagem ent b y Thomas Navin. M alone described th e

lengthy individual and corporate struggle for dom inion over Butte's rich

copper mines. He argued th a t th e struggle for control and Anaconda's

9

hegem ony over sta te econom ic affairs engendered w id esp read prejudice

against big business and a legacy of public resignation — a ttitu d e s th a t

ultim ately affected safety w ith in th e B utte underground. Navin's study

em phasized corporate m anagem ent, in an in d u stry in tim ately tied to high

capital in v estm en t and continuous technological innovation. Navin provided

insight in to Anaconda's place in th e w orld m arket, and th e all im p o rtan t

relationship b etw een copper mining m anagem ent and th e worker.®

During th e last ten y e a rs a n u m b er of w e ste rn historians have tu rn ed

th e ir atten tio n to in d u strial hardrock mining and its occupational hazards,

creating a m ore clear picture of th e im pact of industrialization on th e ru ra l

landscape and population. My stu d y of B utte m iners is p a rt of th is rec en t

historical trad itio n and, if it helps illum inate an u n derstanding of th e im pact

of in d u strial technologies and m anagem ent strategies on th e w o rk er and th e

w ork place and sheds light on how th ese changes below ground w ere

reflected in th e cu ltu re of th e com m unity at large, I w ill have accomplished

m y goal.

10

ENDNOTES

1. In q u est No 8164," Charles Borlace," 13 May 1917, Office of I h e Q e r k o f

l ^ i o n w m 'n o T a p p e a r l^ ^ ^ ^ '

M ontana- !h ereafter rep o sito ry

2. Edwin T. Layton, ed., Technology and Social Q ian se in America (New York:

H arper & Row, Publishers, 1973), 1-8. In his introduction to th is collection of

essays LaytOT defines technology as "knowledge a t w ork w ith in a social

context. This definition helps th e histo rian view th e in d u strial accidents in

B utte in a b ro ad er perspective.

3. Michael Malone. The Battle fo r Butte: Mining and Politics on th e Northern

fro n tie r. 1864-1906 (Seattle- IInivprVi t y n fW a

1981), 11-574. Ronald C. Brown, Hard-Rock Miners: The In term o u n tain W est. 1860-1920

(College Station: Texas A & M D iv e r s ity Press. 1979): M ark W vm an Hard

'm

- " 1n

5. David Emmons, "Im m igrant W orkers and In d u strial Hazards: The Irish

M iners of Butte, 18 8 0 -1 9 19." Iournal of American Ethnic History 5 (Fall

1985); L arry L ankton and Jack K. M artin, "Technological Adv an ce,

Organization, S tructure, and U nderground Mining Fatalities in th e U pper

Michigan Copper Mines, 18 6 0 - 1929," Technology and Culture (Forthcoming).

6. The Anode. F e b ru ary 1 9 1 8 ,5 .

7. V ernon

Metals D

G reever

Minim, and Management

Il

Chapter 2

LIFE ABOVE AND BELOW GROUND ON THE INDUSTRIAL FRONTIER

B eneath a craggy ridge of th e continental divide in th e sparsely

v e g etated u p p er reaches of th e Sum m it Valley located in southw estern

M ontana, sizty m illion y e a rs of complex geologic phenom ena produced one of

th e w orld s rich est deposits of nonferrous m etals—gold, silver, m anganese,

zinc, and copper. Tow ard th e en d of th e n in etee n th c en tu ry , m iners exposed

th e m ineral w e alth b e n e a th th e city of Butte, M ontana — a v e ritab le tre a su re

chest of precious and in d u stria l m etals. During th e last c en tu ry m iners

rem oved n e a rly fiv e billion pounds of zinc, seven h u n d re d million ounces of

silver, and n e a rly th re e million ounces of gold from th e granite underlying

th e B utte hill. But copper m ade th e mining district's reputation. I

The search for copper b rought an in d u strial w a y of life to M ontana.

Thousands of B utte m iners, m any of them im m igrants, lost th e ir lives due to

in d u strial accidents and re sp ira to ry diseases contracted working

und erg ro u nd in B utte b e tw e e n 1880 and 1920. Men died from falling rock,

explosions, hoisting m ishaps, fires, and from inhaling th e silica d u st released

from breaking rock w ith th e m achine d r ill The individual m iner becam e

p a rt of a m uch larger, m ore complex, and som etim es m ore dangerous

technological process of ore extraction, over w hich h e o ften exercised little

c o n tro l To u n d e rstan d fu lly th e im pact of new technologies on th e B utte

12

m iner and th e dynam ics th a t developed betw een th e u rb an com m unity th a t

rap id ly em erged around th e m ines and th e w orld below ground req u ire s

investigation.

From its hum ble beginnings as a gold and silver cam p, B utte grew

into a cosm opolitan city eq u al to its burgeoning new in d u stry , m ushroom ing

from a population of 3.363 in 1880 to 30,470 b y 1900.2 B utte s population

increased tenfold during th e last tw o decades of th e nineteenth century.

Copper mining in sp ired a n urban, in d u strial ch aracter in B utte's architecture

th a t w as m ore rem in iscen t of San Francisco, M assachusetts or Pennsylvania

mill tow ns th a n th e n o rth e rn Rockies of M ontana. C ertainly B utte bore no

resem blance to th e neighboring agricultural com m unities of Bozeman and

Missoula. In th e G littering Hill, a novel se t in B utte during th e 1890s, Q yde

M urphy ap tly p o rtray e d th e incongruity of th e spraw ling mining m etropolis

se t against th e backdrop of its p ristine m ountainous surroundingsT hen cam e a cavalcade of m em ories—of snow crowning th e

d istan t Continental Divide; of droves of m en at shift-changing

tim e, coming off th e hill, now in clusters and again in long th in

files; of th e incessant clam or of stre etca r bells, of th e th u n d e r of

steel w heels on steel rails; of th e screeching of m ine w histles; of

th e sh arp clopping of h o rses' hoofs on th e cobblestones; ...3

M arching up th e flanks of th e B utte hill w e re clusters of w o rk ers'

cottages, sm all hip-roofed w oodfram e houses, b u ilt in close proxim ity to th e

over th re e dozen operating m ines spread across th e hill to w ard th e East

Ridge. The m iners and th e ir fam ilies congregated in e th n ic and occupational

enclaves close to th e ir w ork and th e ir fellow countrym en: in W alkerville

13

(site of B utte's m ost prosperous silver m ines, th e Alice and th e Lexington); in

Centerville, a p redom inantly Cornish and Irish neighborhood; in Dublin

Gulch, adjacent to M arcus Daly's Anaconda Mine; and, in Finntow n,

M eaderville and McQueen to th e east, hom e to Finns. Italians, Serbians.

Croatians, and B utte's m ajor sm elters. These neighborhoods w ere linked to

th e m ines and th e com m ercial d istrict b y a stre e t railw ay as early as 1890.4

From th e intersectio n of P ark and Main, th e h e a rt of B utte's com m ercial

district, an o b serv er could clearly view th e fren e tic econom ic and social life

of th is bustling m etropolis.

By 1900 B utte w as in d isp u tab ly th e econom ic capital of M ontana and

th e m ost significant u rb a n c en ter b etw een M inneapolis and Spokane. An

im posing arch itectu re of stone, brick, and cast iron replaced th e w oodfram e

false fro n ts of th e gold and silver cam p. W ithin v iew of th e b u sy stre e t

co rn er of P ark and Main, th e o b se rv er could look n o rth up th e hill and see

mining b aro n W illiam A. Clark's First National Bank; th e H ennessy Building

(the elab o rately detailed six-story brick d e p artm e n t store and h e a d q u a rte rs

of th e Anaconda Company); th e M iner's Union Hall (the h e a d q u a rte rs of th e

W est's m ost pow erful Ia b w union); and th e im posing black steel h eadfram es

looming along th e hill in th e distance. W hen th e m ines changed shifts,

streetcars, h o rse -d raw n w agons, and m iners clogged M ain S tre et going n orth,

m aking th e ir w a y to and from w ork, each m an re -e n te rin g th e above ground

w orld dom inated b y boarding houses, cafes, saloons, th e a te rs, churches, and

a landscape disfigured b y th e spoils of th e city's mining en terp rise.

Butte, in 1900, bore th e distinctive im p rin t of b o th its in d u strial

14

econom y and its w o rk force. R eports from frien d s and re la tiv e s describing

w ages unequalled in th e mill tow ns along th e E astern seaboard or in th e

Michigan copper m ines lu red European im m igrants to B utte b y th e

.

tho u san d s beginning in 1883. By 1900 over 34 p ercen t of th e Butte

population w as foreign-born, dom inated b y th e Irish, English, and Canadians

w ho com prised a p p ro iim a te ly 64 p ercen t of th e fo reign-born population.^

During th e firs t tw o decades of th e tw e n tie th century, th e ethnic m akeup of

th e population rem ain ed relativ ely constant b u t no t static. By 1910 Finns

constituted 10 p ercen t of B utte's foreign-born; im m igrants from so u th ern

and e a ste rn Europe had increased, w hile Irish and B ritish arriv als had

declined.^

At th e beginning of th e tw e n tieth century, B utte w as a city of m iners;

o v er 60 p ercen t of B utte's ad u lt m ales w orked in th e mines. A t th e sam e

tim e, th o u san d s of m en labored above ground as blacksm iths, ironw orkers,

boilerm akers, c arp en ters, and sm elter m en, in occupations supporting th e

mining in d u stry and in a w ide v a rie ty of oth er businesses th a t supported

B utte's large u rb a n population .7 In addition, th e w ork force in 1900

included 3.000 w om en w orking as teachers, m illiners, clerks, laundresses,

w aitresses, dom estics, p ro stitu tes, and boarding house operators.®

B utte of 1900 b ore little resem blance to th e fro n tie r se ttlem en t

conceived of and described b y Frederick Jackson T u rn er in his

all-encom passing fro n tie r th esis p resen te d in 1893. The thousands of

E uropean im m igrants w ho m ade th e ir w a y to Butte, M ontana betw een 1880

and 1910 bro u g h t w ith th em European religious and social values.

15

T raditional ethnic v alu es p ersisted in th e Irish, Cornish, Finnish, and Italian

com m unities th ro u g h th e religious and fra te rn a l in stitu tio n s th a t w e re

created in th e ir respective neighborhoods b etw een 1880 and 1910. The

in d u strial u rb an ch aracter of B utte resh ap e d th e v alu es of th e second and

th ird generations of th ese im m igrant populations.

These p rim arily ru ra l European im m igrants relied on th e church, and

fra te rn a l and eth n ic organizations and traditions in facing th e perils of

in d u strial em ploym ent and an unfam iliar u rb an w a y of life. Dozens of

churches em erged to serv e B utte’s v a rie d ethnic population: th e Catholic

church predom inated in serving th e large Irish and grow ing Slavic and

Italian com m unities: th e M ethodists follow ed w ith th e ir large Cornish

m em bership; th e Scandinavians continued th e ir L u th eran traditions; and th e

Jew ish com m unity su p p o rted tw o synagogues .10 Dozens of secret societies

also form ed along eth n ic or occupational lines as a m eans of easing th e

tran sitio n into an in d u stria l environm ent. In som e cases, th ese organizations

fulfilled a function beyond m aintaining th e ethnic trad itio n s of th e

hom eland. Such w as th e case w ith th e A ncient O rder of H ibernians (AOH), an

Irish independence organization firs t tra n sp la n te d to A m erica in 1836 and

la ter to Butte. In Butte, th e AOH upheld Irish traditions, b u t m ore im p o rtant,

it sought w ork fo r its m em bers and provided sickness and accident benefits

for its over one thousand m em bers, m ost of w hom w o rk ed in th e m ines .11

Economic o p p o rtu n ity a ttra c te d European im m igrants and

n ativ e-b o rn m iners to th e increasingly dangerous and u n h e alth y conditions

found in th e B utte underground. In 1900 th e single w orking m an

16

p redom inated in Butte. ^^ Clearly, high w ages lu red m any single m en w est.

During th e firs t decade of th e tw e n tie th century, lab o rers in th e steel mills of

Braddock 1Pennsylvania w o rk ed tw elve h o u rs a day for ju st over $2 in w ages

w hile th e B utte m iner, reg ard less of experience, earn ed $3.50 for eight ho u rs

of w ork. *3

W hile th e cost of living w as som ew hat higher in Butte,

relativ ely stable em ploym ent provided o p p o rtu n ity for b o th single m en and

those m en w ith fam ilies. If hom e ow nership re p re se n te d an index of

w orking-class econom ic o p p o rtu n ity and security, th e n B utte in fact did offer

th e im m ig rant m iner p a rt of w h a t prom oters had prom ised. In 1900, o ver 50

p ercen t of th e Irish m iners w ho had lived in Butte fo r b e tw ee n four and

sev en y e a rs ow ned th e ir ow n hom es, and b y 1910 th is percentage w as ev en

greater. *4

R epeatedly, A m erican m en and w om en hav e journeyed w e st for

econom ic o pportunity. Significantly, b y 1900 it w as n o t th e prom ise of gold

or fertile land w hich a ttrac ted thousands to so u th w estern M ontana; it w as

th e possibility of a w eek ly paycheck. B etw een 1873 and 1900, th e United

S tates suffered from periodic econom ic dow nturns, and, a fte r th e Panic of

1893, silver mining in th e W est cam e to a standstill because of th e rep e al of

th e S herm an Silver P urchase Act, m aking good paying jobs in th e Butte

u n derground attrac tiv e to b oth th e native and im m ig ran t w orker. U nder

th ese circum stances, th e prospect of a g u aran teed w age a ttrac ted th e

nations' artisan s and m echanics. 15 But balanced against th e possibilities

p resen te d b y th is n ew life in th e W est w e re th e grim statistics of accidental

d eath und erground and th e e v e r-p re s e n t occupational h azard of m iner's

17

consum ption and debilitating re sp ira to ry ailm ents. Along w ith th e prom ise

of a paycheck, new arriv als from th e g reen hills of W est County Cork,

Ireland, o r from th e fo rested K ew eenaw Penninsula of n o rth e rn M ichigan

encountered a city devoid of vegetation and trees, choked b y th e sulphur

and arsen ic-laden sm oke em itted from th e local sm elters and despoiled by

m ounds of m ine w aste. Confronted b y depressed national economic

conditions B utte's high w ages and th e prom ise of a relativ ely in d ep en d en t

lifestyle initially overshadow ed th ese in d u strial and environm ental

liabilities.

P a rt of th e lu re of underground mining d erived from the

in d ep en d en t n a tu re of th e w ork. Statistics regarding transcience among

B utte m iners b etw een 19 14 and 1920 underscore th is a ttitu d e. During 1914

each job on th e B utte hill w as held b y tw o and on e-h alf m en com pared to

nine m en for each job in 1920, indicating a p e rsisten t m ovem ent from mine

to m ine .1& Dick M atthew , a m an w ho w orked a v a rie ty of jobs underground

in B utte beginning in 1928, described mining as "the m ost in d ep en d en t

laboring job th e re is." According to M atthew , w ho cam e to Butte from a

ran ch in Choteau, M ontana, th e m iner "designs his ow n w o rk and th e re ain 't

nobody looking dow n y o u r collar." ^

The m iners' in d e p e n d e n t n a tu re

d eriv ed p a rtly from th e large n u m b er of job prospects.

An e itre m e ly rich

and extensive mining d istrict and a growing dem and for copper, and la ter

zinc and m anganese, created alm ost unlim ited o p p o rtu n ity for th e

experienced m iner. Endless o p p o rtu n ity tran sla te d in to an occupational

independence th a t often clashed w ith th e complex technological process

18

engineered b y corporate m anagers, creating unforeseen hazards

und erg ro u nd for th e w o rk er. By 1900 th e Butte m iner found his life divided

b etw een tw o v e ry d ifferen t b u t connected w orlds.

The unflagging en erg y in th e stre e ts of B utte in 1 9 0 0 - th e throngs of

m en and w om en freq u en tin g th e shops along East Park, th e clanging

streetcars clim bing up Main, th e new sboys on th e corners haw king papers,

and th e m usic and c h a tte r drifting ou t of th e cafes and saloons on Main

S tre e t— m im icked th e activity day and nig h t in th e can d le-lit passagew ays

tho u san d s of fe e t b e n e a th th e stre e ts of Butte. W hile th e snow fell and

te m p e ra tu re s above ground plum m eted to -20 degrees Fahrenheit, th e

m iners, strip p ed to th e ir w aists, p rep a red fo r a d ay of w o rk in a dim ly lit

stope w h e re te m p e ra tu re s reached 90 degrees F ahrenheit.

More th a n 2,000

fe e t se p arated th ese tw o w orlds: th e w orld above distinguished from th e

one below b y th e w o rk perform ed, th e w ork place itself, and th e language

spoken.

As e a rly as 1890, m iners practiced th e ir tra d e in m ore th a n thirty

mines, v ary in g in size fro m tw e n ty to fo u r h u n d re d em ployees, dispersed

across th e B utte hill. I & R egardless of size, th e p rim a ry task rem ained th e

same: follow th e o re v e in and g et th e ore to th e surface. The size of th e

m ine did, how ever, som etim es a lter th e tools used to accom plish th is task.

Moving larg er volum es of m en and ore to and from th e surface req u ire d th e

aid of m ore com plex tools and m achinery. For exam ple, a sm all mining

operation of tw e n ty to one h u n d red m en m ight re ly on h an d drills for

breaking th e rock and a b u ck et and sm all steam hoist fo r transporting m en

19

and ore to th e surface, w hile a m ine em ploying h u n d re d s of m en w ould

p robably use m achine drills and a system of cages and skips for th e

m ovem ent of m en and ore.

W hile th e size and sophistication of th e mining operation in Butte

v aried enorm ously, th e length of th e w ork day did not. The ten -h o u r day

prevailed until 1905 in th e m ines of th e A m algam ated Copper Company,

w hich controlled approxim ately tw o -th ird s of th e w orking B utte mines,

e v en though th e sta te legislature m andated an eig h t-h o u r day in 19 0 1.19

W hile th e sm aller m ines like th e T ram w ay and th e Belle of B utte w orked a

single shift, th e larger m ines like th e M ountain Con and th e Anaconda

o p erated tw o and som etim es th re e shifts, to am ortize th e ir larg er capital

in v e s tm e n t B utte m iners w orked seven days a w eek, averaging

tw e n ty -sev e n days a m onth, and received tim e off only w h e n th e shaft

n eed ed rep a ir or th e m achines m aintenance. During th e e arly y ears, th e

P arro t w as th e only m ine of a n y size to give its w o rk e rs a Sunday holiday .20

The w o rk d a y o rd in arily began for m iners on th e day shift a t seven

a m- A fter donning w ork clothes in th e "dry" o r change house, m iners

g ath ered around th e sh aft collar (surface opening) to aw ait tran sp o rta tio n in

a b u ck et o r cage dow n th e sh a ft to th e ir assigned level and w ork station.

The bucket, large enough fo r tw o or th re e m en to stand, w as attached to a

m anila - later, w i r e - rope, and descended dow n th e sh a ft b y m eans of a

steam -p o w ered engine. This hoisting engine w as ev en tu ally pow ered by

com pressed air and la te r electricity. The ro p e ra n up o v er a sheave w h eel

(pulley) located a t th e top of th e h eadfram e, a four-legged w ooden and later

20

steel stru c tu re located o ver th e shaft collar, and w as attach ed to a large

cylindrical drum (10 to 20 fe e t in d iam eter) located in th e hoist house. As

th e size of th e operation expanded, th e bu ck et w as u ltim ately replaced b y a

cage, a steel conveyance no t unlike an elev ato r car, w ith in w hich five to

sev en m iners could stand to be hoisted. Eventually skips, large steel boxes

capable of holding from seven to te n tons of rock, carried th e ore to the

surface .21

M iners travelling to and from th e w ork station e n tru ste d th eir

safety to th e sta tio n ary engineer. The engineer raised and low ered th e

cages and skips guided b y e ith e r a n audible bell system or a visible set of

lights linked to a signal a p p aratu s located a t e v e ry level. T here w as a station

te n d e r a t each level (norm ally e v e ry 100 fe e t) w hose job it w as to load m en

and m aterials and signal its d estination to th e engineer. In Hardrock Miners

Ronald C Brown a p tly described th e m iners' sense of helplessness as th e y

descended to th e w o rk place:

As th e w arning bell sounded, th e cage dropped in to th e dark

shaft. The only light cam e from lan tern s affixed to th e cage

itself and from those passed on th e w a y down. L ikened b y

som e m iners to being b u ried alive, th e fall produced only m uted

sounds, th e sm ell of dam p ground, and th e ru sh of air; th e n

from th e p it of th e stom ach cam e th e sinking feeling th a t

accom panied th e rap id fall .22

At an e arly d ate m iners ale rte d th e territo ria l legislature to th e

dangers associated w ith th e b u ck et and th e open cage, such as m en falling

from th ese conveyances from d izzin ess or catching clothing or tools against

th e sh aft walls.

As e a rly as 1887, M ontana passed a law prohibiting w ork in

21

a vertical sh aft below th e 300-foot level w ith o u t an iro n - b onneted safety

cage.^^

By th e e arly p a rt of th e tw e n tie th cen tu ry , en g in eers im proved th e

iro n -b o n n eted cage b y adding on e-h alf inch iron plate on th re e sides and a

four-fo o t safety gate on th e front. Even th ese safety fe a tu re s did no t

elim inate hoisting fatalities or th e apprehension of m iners about dropping as

m uch as 3,000 fe e t in to th e e a rth a t a speed of from 500 to 800 fe e t per

m inute.

Having a rriv e d a t th e ir w o rk level, th e m iners proceeded from th e

statio n (an enlarged a re a adjacent to th e shaft) into th e d rift (a fo u r- to

eight-foot w ide horizontal tu n n e l th a t follow ed th e orebody), th e w a y lit only

b y candle or torch. Electric lights ap p eared in th e W alkerville silver m ines

as e a rly as 1 8 8 1, b u t th e shafts and d rifts in th e m ajority of B utte m ines

w e re n o t lit electrically u ntil th e 1890s. Carbide lam ps replaced candles for

light in th e B utte slopes around 19 12.24

Crosscuts, or horizontal tun n els

connecting orebodies, in tersected th e drifts.

The job com m enced w h e n th e m iner reached his assigned w ork

station. Tasks ran g ed from th e m ost unskilled m ucking (shovelling ore or

w aste into a car or dow n a chute) and tram m ing (pushing an ore car dow n a

track to th e station fo r loading) to th e highly skilled tra d e of blasting and

tim bering. M iners generally w o rk ed in pairs following th e ore v ein e ith er up

(an o v erh ead slope) or dow n (an u n d erh an d slope) from th e level w ith

h am m er and steel and blasting pow der. W ith contract mining, a popular

em p lo y m en t system in B utte, th e am ount of rock rem oved or b ro k en during

a day d eterm in ed a m an's w age. Four m en, w orking as a team on opposite

22

shifts, perform ed all th ese v ario u s tasks. The m iner rem oved th e ore from

th e v e in b y drilling a n u m b e r of s ii- to eig ht-foot-deep holes, one to tw o

inches w ide, into th e B utte granite. T hen he loaded six to tw elve holes w ith

dynam ite arid ignited th e charge, bringing dow n tons of rock in a tim ed

series of blasts. Until th e late 1890s, th is drilling w as done b y tw o m en

w ith o u t pow er tools, one w ielding a sledge and th e o th er holding and tu rn in g

a h an d steel, a skill perfected o v er th e cen tu ries in th e tin m ines of Cornwall

and passed on th ro u g h Cornish im m igrants w orking in th e copper m ines of

Michigan and th e silver m ines of N e v a d a #

A lthough th e labor-saving

m achine drill ev en tu ally replaced th e physically dem anding technique of

hand-drilling, th e p rim a ry task of ore rem oval rem ain ed virtually

unchanged.

The task of ore rem oval could n o t b e accom plished w ith o u t th e

specialized skills of an in d u strial w ork force th a t included pum pm en

(assigned to keeping th e w o rk place fre e of w ater), m ule skinners, and la ter

m otorm en (charged w ith delivering th e ore car from th e d rift to th e station),

sh aftm en (em ployees w h o tim b ered th e descending shaft), and sam plers,

surveyors, and geologists (specialists w ho analyzed th e orebody and ch arted

th e course of developm ent). The underground operations also relied on a

h o st of m en on th e surface including topm en (w orkers responsible for

rem oving th e ore cars and m en from th e cages), saw yers, blacksm iths,

m achinists, electricians, com pressor m en, rope m en (m en charged w ith

m aintaining and replacing th e w ire rope used fo r hoisting), and team sters,

la te r replaced b y locom otive m en. Still, th e m ajority of m en actually

23

w orked underground; th e re w as approxim ately one m an on surface for

e v e ry fo u r underground. Those w orking underground took o rd ers from th e

shift bosses, w ho m ight su p erv ise from tw e n ty to sixty m en, and th e bosses

took th e ir lead from th e m ine fo rem en and th e su p e rin te n d en t on top, and

th e assistan t fo rem en w orking underground.

The B utte m iner m ay hav e b een less closely supervised th a n his

contem poraries toiling in a Pennsylvania steel mill, b u t th e labor w as n e ith er

any less dem anding, nor w e re th e conditions any less trying. For eight to te n

ho u rs a day, th e m en h ired to bring th e copper ore to th e surface perform ed

physically exhausting labor in a confined environm ent, a w orld unto itself.

The m iner typically sp e n t his e n tire day or night in p e rp e tu al underground

darkness, laboring in a slope o r raise ju st high enough for a m an to stand

e re ct a t te m p e ra tu re s as high as 107 degrees F ah ren h eit a t 100 p ercen t

hum idity. At th e 38 0 0 -fo o t level of th e S tew art Mine, n o t only did th e air

te m p e ra tu re s reach th e se extrem es, b u t also th e w a te r pum ped from th e

slopes th e re reached 1 13 degrees Fahrenheit.^ ^

W here th e w ork place w as not h o t and hum id, an o th er potentially

m ore hazardous condition persisted: d u sty air. The silica d u st th a t filled th e

air from th e m achine drill posed an unseen danger to th e m iner: m iners’

consum ption or silicosis, an often fa ta l lung disease. Until 1916 m iners

drilled practically all slopes w ith o u t w ettin g th e surface, creating an

epidem ic of re sp ira to ry diseases underground unm atched in any other

in d u stry .^ ?

John Gillie, g eneral su p e rin te n d e n t of A m algam ated Copper

Company, testified before a fe d e ra l in d u stria l relations com m ission in 1914

24

th a t d u st w as an in h ere n t, unavoidable aspect of mining. In a single y ear,

according to Gillie, m iners d etonated over four million pounds of pow der in

th e Butte underground, filling poorly v en tilated slopes w ith dead ly g ranite

dust.28 The introduction of w e t drilling districtw ide b y 1925 even tu ally

im proved th e d u st problem , b u t failed to elim inate th e d ead ly hazard.

Ju st as th e h e a t and d u st read ily dim inished th e stre n g th of e v en a

young m an w orking underground, so did an atm osphere lad en w ith th e

sm ells of h u m an and anim al excrem ent, pow der, sw eat, and rotting food.

H undreds of m en sh ared th e ir w orkspace w ith th e m ules enlisted to pull ore

cars to th e station. Not until 1923 did ACM com pletely replace th e m ule

w ith electric locom otives.29

Toilet cars did not m ake w idespread

ap p earan ce in th e B utte d istrict u n til afte r 1916, forcing th e m iners to

reliev e th em selv es w h e re v e r convenient and creating an u n san itary and

fertile en v iro n m en t fo r disease and verm ine.

Life u nderground did n o t accom m odate those w eak of h e a rt or mind.

Even th e young and physically ro b u st could b arely e n d u re th e heat, bad air,

noise, darkness, and stren u o u s w o rk of th e underground. In 1915 Jacob

Oliver, an experienced m iner of th irty -fiv e y e a rs and th e Deputy State Mine

Inspector b e tw ee n 1890 and 1892, testified before th e Commons

Commission on In d u strial Relations th a t th e average life of a m iner u n d er

co n tem p o rary conditions w as sixteen y ears.3 0

At $3.50 a day, th e w ages of

a B utte m iner w e re high, in fact alm ost tw ice th a t paid M ichigan copper

m iners.3 1 Yet th e high w ages did no t com pensate fo r a w o rk life cut sh o rt

b y a disabling injury, a fa ta l in d u stria l accident, or th e crippling disease of

25

m iners consum ption. The throngs of European im m igrants w ho m ade th e ir

w ay to B utte to w ork in its copper m ines found a perilous w ork

environm ent, inhabited b y unfam iliar m achines, routines, and unforeseen

hazards.

26

ENDNOTES

4 7 .6 3 5 . and th e city of B utte dom inates th e county.

M urphy. Ihff Olitterm g Hill (New York: W orld Publishing Co..

f

H iZ v n ° ;,^

B utte Rail Connection: Mining and T ransportation,

S[! t . »

:, A,!P urnal ^

"H

M ontana

5. A bstract of t he 12 th Census of th e IJ S 106.

P r i n ^ g ^ f i c e % 3 ^ 2 1 ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ e U.S,. (W ashington: G overnm ent

Ir A b stract of th e 12th Census of th e US.. Special R eport (Washington;

G overnm ent P rinting Office,1904), 4 3 2.

6

8. M ary M urphy. "W om en's W ork in a M an's W orld," The Speculator A

M im a l Qf ButtC and S outhw est M ontana History I f W i ^ r W a T I Q

According to M urphy, tw e n ty -tw o p e rc en t of B utte's 13.000 w om en w orked

as w age earn ers.

9. Dale M artin and B rian Shavers. "Butte, M ontana: An A rchitectural and

Historical In v en to ry of th e N ational L andm ark District," an unpublished

rep o rt, B utte Historical Society. 19 8 6 .3 1-53.

10. Ibid.

12. A b s t r a c t s tire 12 th Census 131. A bstract of th e 13th Census. 166

m ra w e re maiTied. This n u m b er

In

14. Emmons, "Im m igrant W orkers and In d u strial Hazards," 58. This figure

on hom e ow nership is extracted from th e m anuscript censuses of 1900 and

1910. It is derived from a sam ple of 193 Irish m iners and it includes only

those w ith children, excluding those w ho are single or childless.

economic depressions in A m erica b e tw een 1873 and 1893.

J[6- Paul FuB rissenden, "The Butte M iners and th e Rustling Card." A m erican

Economic Review (December 1920): 770.

17. Dick M atthew , in terv iew w ith author, Butte, M ontana, 24 Jan u ary 1986.

° f M nm m a

<Helena;

19. U.S. Commission on In d u strial Relations. Mining Conditions and

I u^ gl

Senate G m i w n t 4 15764th Congress,

! ! S M

iB S K

J r w

M ,V-

IBMealier

21. Brian Shovers "The Emergence of a W orld-Class Mining District: A

,tS MineyardV unPubtehed

i Rkn^0I1Ivln ?; B row n,H ard-Rock M iners: The In ter m ountain West.

1 8 6 0 -1 9 2 0 (College Station, Texas: Texas A&M U niversity Press, 1979), 67.

W ^ f re

Perils of hoisting m en, see 92 -1 0 2 in Mark

J^S S ^lS^VAde^i&wersrty1o u j l i i S l I m a ^fvflPltinn

23. Mine Inspector R eport 1889 96.

£ I-W y man, Iitrd-Rock Epic. 103, for inform ation on electrification of Butte

mines. Dating of th e introduction of th e carbide lam p from in terv iew w ith

Ed Shea, in terv iew w ith author, Butte, M ontana, 23 Ja n u a ry 1986.

gsaeijM

13' I he exact date th a t th e m achine drill

Mine 97

ntl0ns lh e use of Ingersoll-S ergeant drills a t th e M ountain Con

28

27. Ibid., 12.

28. "Commons Commission Report," 3950.

29. William B. Daly, et. al., "Mining M ethods in th e Butte District,"

24^87tS Qf MlDinR Enginggr? VoL LXXI1*1925

30. "Commons Commission Report," 3916.

31. -Mine Inspector Report 1889 H2.

29

Chapter 3

NEW TECHNOLOGIES AND THE DYNAMICS OF THE WORK PLACE

In th e e arly p a rt of th e tw e n tie th century, the U.S. D epartm ent of

Labor considered mining a v e ry dangerous occupation, and for good reason.

The fa ta lity ra te for an A m erican m etal m iner in 1908 w as alm ost th ree

tim es g rea ter th a n th a t of a com bat soldier.* On June 2 0 ,1 9 0 9 , th e Butte

MiflSL rep o rte d th e following gruesom e incident, a trag e d y th a t underscored

th e labor d e p artm e n t's statistics:

Sirois a top m an at th e M oonlight mine, b e tte r know n as Joe

King, m et a ho rrib le d eath b y being hoisted up in to th e sheaves at

the m ine y e ste rd a y m orning. Sirois w as h u rled from the cage

alm ost as soon as it cam e in contact w ith th e sheave w heel and fell

a distance of 1550 fe e t to th e sum p. The body w as reduced to a

^ ssyOf bones p ro truding from th e to rn and bleeding flesh. It w as

unrecognizable.

That v e ry sam e y ear, fo rty -fo u r o th er m iners, m any of them

foreign-born like Sirois. lost th e ir lives b en eath th e B utte hill. In th is case,

like nu m erous o th er accidents th a t occurred during th is e ra in Butte, th e

u n fo rtu n ate French-C anadian m iner had no control o ver his ow n fate; a

m achine caused his death, a m achine im properly o p erated by an apprentice

hoist engineer. A v a rie ty of circum stances, ranging from th e instability of

local orebodies to th e use of complex n ew mining technologies to a reliance

on an u n train ed and fiercely in d e p e n d e n t w ork force, m ade th e Butte mining

district m ore dangerous th a n its E uropean counterparts, particu larly during

th e early p a rt of th e tw e n tie th cen tury.

The w id esp read use of m ore complex m achinery in th e Butte

30

underground b y 1890 created a new, som etim es dangerous dynam ic within

th e w ork place. Beginning in 1890 th e e n tire mining operation becam e

larger, m ore complex, and infinitely m ore difficult to supervise. During a

tim e w h en technological change req u ire d a highly trained and carefully

supervised w ork force, large n u m b ers of untrained, ru ra l European

im m igrants peopled th e B utte underground. A horrific loss of life,

unparalleled in A m erican in d u strial history, m arred th e tran sitio n from

sm all-scale trad itio n al h ardrock m ining to large-scale in d u strial mining in

Butte.

B etw een 1860 and 1910, th e invention and application of new mining

technologies revolutionized hardrock m ining in th e A m erican West.

Machines replaced h and labor in drilling, hoisting, and tram m ing, allowing

m iners to reach d ep th s and production levels previously ou t of reach. The

introduction of electricity to th e underground p e rm itte d another surge in

productivity, as w ell as im proved th e m iner's w ork en v iro n m en t through

b e tte r lighting and v entilation.^

As mining h istorian M ark W ym an points

in Ha rd -Rook Epic, how ever, th e new breed of mining machinery also

contributed to an alarm ing increase in underground fatalities. Corporate

industrialists, often geographically rem oved from th e trag ed ies regularly

occurring on th e ir properties, took little tim e to w eigh th e hu m an im pact of

new technologies.^

The tran sitio n from h an d drill to m achine drill h ap p en ed o ver a

fifte en -y e ar period. Trial and e rro r even tu ally produced a tool light enough

to be o p erated b y a single m an and d u rab le enough to w ith stan d th e rigors

of th e underground. It did n o t tak e m ine m anagers long to recognize th e

productive advantages of th e su p e rh u m an m achine drill. At th e Quincy Mine

31

in Michigan, th e Rand drill enabled 50 p ercen t few er m iners to produce 50

percen t m ore copper. By 1895 th e L eyner, and Ingersoll & Rand m achine

drills prevailed on th e B utte hill, alm ost com pletely replacing th e hand

sledge and steel. Som ew hat earlier, dynam ite replaced black pow der, again

increasing th e m iner's productive capabilities w ith its superior

g round-breaking a ttrib u tes.^

W hile m ine su p e rin te n d en ts tallied up m ounting dividends, th e Butte

obituaries recorded th e legacy of th is new m achine technology. The m achine

drill filled th e u n v en tilated slopes w ith silica dust. Inhaled b y m iners, these

sh arp -edged d u st particles scarred th e lungs of unsuspecting w orkers,

creating an epidem ic of tuberculosis and resp ira to ry disease among m iners.

A significant n u m b er of B utte m iners b etw een th e ages of tw en ty -fiv e and

fo rty -fo u r filled th e local cem eteries, and b etw een th e y e a rs 1907 and 1914,

over 50 percent of th e m iners w h o died w ithin th a t age group succum bed to

a resp ira to ry disease.5

A national public ou tcry u ltim ately prom pted a technological solution

to this d evastating h ealth hazard, b u t thousands of B utte m iners died before

m ine ow ners introduced w e t drilling and m echanical v e n tilatio n system s to

ab ate th e dust. By 1914, ACM installed 150 Ram w a te r drills, a drill th a t

h ad proved successful in Arizona m ines in reducing th e d u st level, and by

1925 all th e com pany m ines had converted to w e t drilling.^

In F ebruary of

1918, ACM organized th e firs t ve n tilatio n and hygiene d e p a rtm e n t in the

copper in d u stry , and th e d e p a rtm e n t supervised th e installation of eighteen

rev ersib le surface fan s and an additional one thousand auxiliary fans

u n derground as w ell as fo rty miles of flexible air ducts to c a rry fre sh air into

th e d rifts and s lo p e s / W hile im proved drilling and ven tilatin g technologies

32

g reatly im proved underground w orking conditions, re sp ira to ry disease

rem ained a h e alth th re a t w ell into th e tw e n tieth c en tu ry due in p a rt to a

reluctance among som e m iners to em brace th e safer new techniques.^

The enorm ous increases in ore production in Butte b etw een 1883 and

1900 cannot be a ttrib u te d solely to th e w idespread use of th e m achine drill

and dynam ite. New hoisting and tram m ing technologies proved equally

im portant. Initially, th e steam -p o w ered hoist constituted a danger to th e

'

m iner accustom ed to th e m uch slow er horse-pow ered w him and bucket

system . In 1887 cage-related accidents accounted for 30 percent of th e

’

deaths, and as late as 1896, hoisting accidents still accounted for 35 percent

of th e fatalities. But by th e y e a r 1916, a record y e a r for m ine fatalities,

hoisting accidents constituted only 5 percent of th e know n fatalities. ( See

Table I at end of chapter.)

The invention of various safety devices for hoisting engines and cages

greatly dim inished th e danger of riding th e cage to and from th e surface.

Probably a dozen m en lost th e ir lives in Butte betw een 1887 and 1920 w hen

th e hoist engineer failed to sh u t dow n th e engine, running th e cage into the

sheaves at th e top of th e headfram e. Beginning in 1910, ACM installed th e

Welch Cut-Off—an autom atic braking system th a t stopped th e cage w hen th e

engineer neglected to do so—to p re v e n t overw inding.

As e arly as 1909,

added insurance against engineer e rro r appeared e v en in th e sm aller mines

in th e form of a bell and light signal system .^

Flashing electric lights

com bined w ith th e ringing bells to alert th e hoist engineer to th e cage

location and its desired destination.

Accidents still occurred occasionally w h en th e station te n d e r ignored

th e gate-closing rule or w h e n th e safety device m alfunctioned. In August

33

1898, a hoist engineer at th e Original Mine lifted the cage to th e 300-foot

level from th e 1,000-foot level w h e re th e w ire rope broke and th e safety

dogs failed to catch on th e cage guides. Ironically, another engineer and th e

deceased m iner had inspected th e rope ju st tw o days before th e accident

w ith o u t noting any defects in th e five-m onth-old rope. Deputy Mine

Inspector Frank H unter testified before a coroner's ju ry th a t rope defects

w e re m ore difficult to detect on a ro u n d rope, especially w h en th e rope had

b een covered w ith a protective covering of tar. H unter also rep o rted th a t

tw o -th ird s of th e safety dogs inspected w e re ineffective. The dogs caught

during tests on th e surface but, w h en p u t to th e te s t w ith th e cage in

operation, th e y in v ariab ly failed, putting th e lives of those in th e cage a t

risk .10

W hile m ine o p erato rs clearly benefited from th e use of m achines,

th e m iner w as no t alw ays so fo rtu n ate.

New tram m ing technologies, such as th e und erg ro u n d electric

locomotive, m ade possible th e m ovem ent of tw ice th e ore in half th e tim e.

But again, th e new technology exacted a hum an cost. Until 1907, th e

tram m e r m oved ore from th e stope to th e level statio n w ith a car pulled by

horses and mules, b u t th e horse ultim ately relinquished its role to a 2 5 0 v olt DC m otor capable of pulling a load of tw elve tons. By 1923, a team of

tw o h u n d red fo u r-to n tro lley locom otives hauled ore along th e d rifts of th e

ACM mines, retirin g all b u t tw o m ules on th e B utte h ill.11 W hile electricity

re p re se n te d an inexpensive source of pow er for tram m ing, m iners fell p rey

to certain h azards associated w ith th e new technology. In th e narrow , dim ly

lit drifts, a carelessly suspended tro lley w ire re p re se n te d a d eath tra p for

th e in atten tiv e tram m er.

Even though electricity constituted an invisible danger if used

34

im properly, th e adap tab le new pow er source also g u aran teed v astly

im proved w orking conditions for all those w ho labored underground.

Electrical pow er m eant th e possibility of a b e tte r lit and b e tte r v en tilated

w ork environm ent. Candles had b een th e p rim ary source of lighting in th e

slopes until th e introduction of th e carbide lam p around 1912. Not only did

candlelight h am p er th e m iner s view of unprotected chutes or m anw ays,

occasionally leading to fa ta l falls, b u t a forgotten candle also ignited a tim b er

in th e Pennsylvania Mine in 1916, causing a tragic fire th a t claim ed th e lives

of tw en ty -o n e m iners. A carbide lam p, w hich ignited th e oily insulation on a

lead electrical cable being low ered dow n th e Granite M ountain shaft of th e

Speculator Mine, sta rte d a fire th a t caused th e w o rst hardrock mine d isaster

in th e n ation's history, claim ing 164 lives. The adoption of a

b a ttery -p o w ere d electric m iner's lam p in th e 1930s ev en tu ally elim inated

th e open flam e from th e w ork place. 12

Electricity also p artially solved underground v e n tilatio n p ro b le m s.1

The rep lacem ent of steam -p o w ered engines and pum ps w ith

electric-pow ered appliances reduced w orking te m p e ra tu re s dram atically.

More im portantly, electricity pow ered th e e ite n s iv e m echanical v entilation

system installed across th e B utte hill afte r 1915. The large rev ersib le fan s

located on th e surface cooled th e w ork space w ith a continuous circulation of

fre sh air and could be m anipulated to re d ire ct th e flow of sm oke and gases

in th e e v e n t of fire u n d e rg ro u n d .^

Over th e fo rty y e a rs beginning in th e 1870s th e B utte m iner

w itnessed a m ajor tran sfo rm atio n of th e w ork place. M achines replaced th e

hand drill; electric pow er replaced steam for hoisting; and th e

tro lley —follow ed ev en tu ally b y a b a ttery -p o w ere d locom otive—replaced

35

horsepow er for tram m ing. The introduction of th ese new technologies

coupled w ith a g rea tly expanded w ork force, capital in v estm en ts of major

proportions, and m ore efficient m ethods of sm elting and refining, accelerated

Butte s ascendency to th e ra n k of w orld s largest copper producer by

18 8 7 .14 W hile new technologies proved a mixed blessing in th e w ork place,

a n u m b er of n ew h azard s a p p eared as th e w o rk er profile and m anagem ent

of th e w ork force evolved w ith corporate control of th e B utte mines, fu rth e r

distancing th e u n train ed im m igrant re c ru it from th e skilled v e te ra n of the

underground.

B utte m ine ow ners, large and small, enthusiastically adopted th e use

of new technologies w ith little thought as to th e ir im pact on th e w orker.

During Butte s infancy as an in d u stria l mining cam p, m uch of th e w ork w as

done b y highly skilled Cornish and Irish m iners, b u t beginning in th e 1890s,

th e ethnic tex tu re of th e w ork force changed w ith an infusion of

p redom inantly ru ra l im m igrants from Italy, Croatia, S erbia and B ohem ia.15

These experienced tillers of th e soil a rriv e d in B utte ill-equipped to m eet th e

dem ands of an in d u stria l w ork place in th e process of technological

transform ation. W hile 80 p e rc en t of th e im m igrants from th e British Isles

w orking in A m erican m etal m ines during th is period had previous mining

experience, only 5 p ercen t of th e southern and e a ste rn E uropeans had

w orked u n derground before. 1^

Beyond th e problem of inexperience em erged a p e rsisten t conflict

b etw een tw o v e ry d ifferen t cultures: th e tw e n tieth c e n tu ry w orld of

m achine w ork v e rsu s a n in e te e n th c en tu ry p re-in d u strial, agricultural w orld.

The E uropean im m igrant cam e from a w ork w orld defined b y th e land,

seasons, fam ily, th e church, and village, in w hich tru s t and cooperation

36

p erv ad ed w ork relationships. In th e B utte mines, th e ru ra l im m igrant

confronted a hostile, su b te rra n e a n en v iro n m en t of sm oke, in ten se h e a t and

noise, w ith o u t com m and of th e language or th e skills and experience

n ecessary to do th e w ork safely and efficiently. As labor histo rian H erbert

Gutm an noted in his classic study, W ork. Culture and Society in

In d u stria lizing Am erica, th e ru ra l su b -cu ltu re w ith in th e im m igrant

population p ersisted in th e face of industrialization. The im m igrant

relinquished trad itio n al w ork hab its and ro u tin es reluctantly, especially

since th e new arriv al of peasants, fa rm e rs and a rtisan s from Europe

periodically rev iv e d ru ra l v a lu e s.17 Boarding th e cage each day, th e

im m igrant m iner tra v e lle d from th e fam iliar w orld of neighborhood and

fam ily into an alien u nderground e n v iro n m en t w h e re a b rief m om ent of

in atten tio n could prove fatal.

Inexperienced im m igrants often found th em selv es doing dangerous

w ork th a t th e m ore experienced n o rth e rn Europeans avoided through

seniority. U naw are of p o tential dangers and o ften unable to u n d e rstan d

directions from English-speaking p artn ers, th e im m igrants faced a m uch

higher degree of risk. The novice's firs t u nderground assignm ent w as

norm ally mucking, a ta sk in w hich th e "greenhorn" relied com pletely upon

th e direction and ju d g m en t of his m ore experienced p a rtn e r. A fo rtu n ate

novice m ight be team ed w ith a m an willing to sh are his know ledge of th e

w ork place and its in h e re n t hazards, b u t m ore typically th e experienced

m iner resen te d th e inexperienced m an, p articu larly if th e n ew re c ru it's

in ep tn ess slow ed production.

Frederick Hoffman, w ritin g about th e problem of in d u strial accidents

for th e Bureau of Labor S tatistics in 1915, cited inexperience as a factor

37

contributing to a large n u m b e r of accidents. In both th e m etal m ines of th e

Am erican W est and th e South African T ransvaal, th e w orld's tw o m ost

dangerous regions to w ork underground, im m igrants predom inated. In both

instances th e w ork force consisted of m en im ported from agricultural

com m unities w h e re th e in h ab itan ts w e re ignorant of m achinery and

unaw are of th e potential danger in h e re n t in th e w o rk .18 A young T urkish

im m igrant nam ed M ahm ada Kaki died from a fall of ground in a B utte m ine

after ignoring e ip licit instructions from th e shift boss to drill and blast out

th e w aste rock to m ake room for a tim ber. In stead th e inexperienced m iner

tu rn e d his drill into th e ore w ith com plete disregard fo r w h a t th e shift boss

reg ard ed as com m on-sense p ractice.1^

Knowledge of safe and efficient m ethods d eriv ed p a rtly from

fam iliarity w ith th e task and p a rtly from training. Supervised training w as

not available in an y of th e B utte m ines b etw een 1880 and 1920. The novice

m iner w as typically given a shovel, assigned to a level and a slope, and p u t

to w ork w ith o u t having to dem o n strate his com petence. By contrast, in

Europe a m an did not becom e a m iner w ithout a long apprenticeship u n d er a

m aster.

A good m iner is a skilled craftsm an, like a c arp en te r or smith,"

w ro te ed itor Richard Rothwell in th e S eptem ber 1897 issue of th e

Engineering fr Mining lournal as he

decried th e h azards associated w ith

em ploying th e inexperienced m iner. Rothwell fu rth e r o b serv ed th a t in th e

m etal m ines of w e ste rn United S tates "m en fre sh from th e farm or bench go

to w ork and w ith in a m onth or tw o call them selves m iners." According to

th e editor, th e self-proclaim ed m iners' ignorance of safe mining practices

constituted an e v e r-p re s e n t m enace to them selves and others.^®

M any of Butte's und erg ro u n d tragedies can be linked directly to

38

in ad eq u ate training and an absence of em ploym ent stan d ard s. The forem an

asked only tw o questions of tw e n ty -fo u r-y ea r-o ld R hinehart C hristm an the

day h e w as h i r e d - th e v e ry sam e day h e died from a fall dow n a chute at

th e M ountain View Mine: "Are you a m iner? " and "W here did you w ork

before coming here?" A lthough th e young m an claim ed experience in

Colorado silver m ines, th e fo rem an a t th e M ountain View lacked any m eans

of verification except th e re c ru it's p e rfo rm a n c e .^

By contrast, m iners

coming from th e m ines of G erm any and Cornwall w e re p a rt of a

centuries-old ap p renticeship tradition.

A m iner s training in six tee n th -c en tu ry G erm any and on into th e early

tw en tieth c en tu ry began a t age te n w orking above ground at sorting tables.

Initiation to th e u n derground occurred only a fte r six y e a rs at sorting and

pushing ore cars to th e shaft. At age tw e n ty th e young G erm an silver m iner

apprenticed for seven y e a rs a fte r w hich h e took a journeym an's test. A

journeym an m iner enjoyed a privileged statu s in G erm an society, entitling

him to th e rig h t to b e ar arm s and exem ption from m ilitary service and some

general taxes. Cornish m iners perform ed an equally lengthy apprenticeship,

beginning w ork above ground b e tw ee n th e ages of nine and tw elve, sorting

rock fo r milling before going und erg ro u n d w ith his fa th e r or uncle to learn

th e skills of drilling, blasting and tim bering. The m ine ow ners in Cornwall

w ere w ell aw are of th e skills and experience of th e ir e n tire w ork force, since

individual fam ilies m aintained an occupational h eritag e th a t stretch ed back

in tim e over generations.22

In contrast, B utte m ine ow ners em ployed a

largely ru ra l im m igrant w o rk force a fte r 1900, com posed of m any w ho had

n e v er b een u n derground before. Because of th e trem en d o u s dem and for