Substitutability of recreational activities by Teresa Anne Spencer

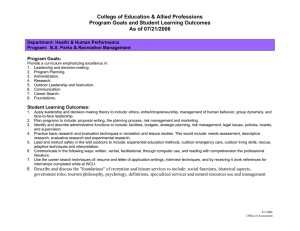

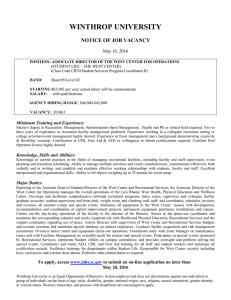

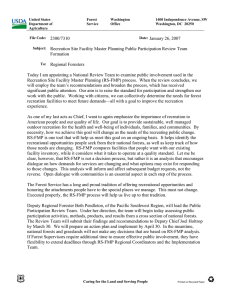

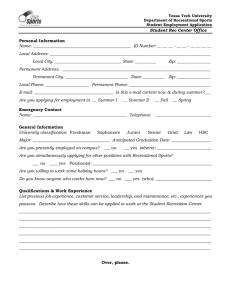

advertisement