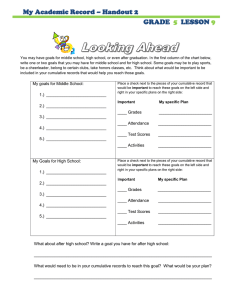

The usefulness of cumulative records in the elementary school

advertisement