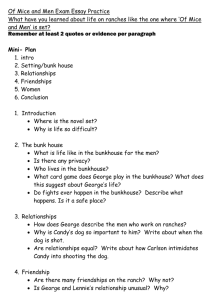

Labor use on livestock ranches in Montana by George H Biddle

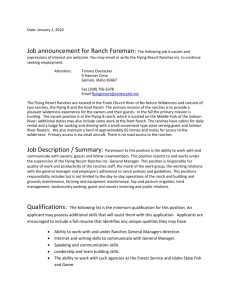

advertisement