Development and evaluation of audio-visual aids for the teaching of foods by Carol Ann Harper

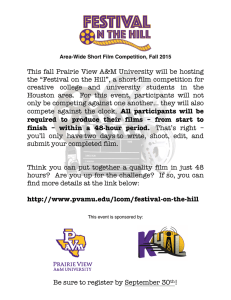

advertisement