T

advertisement

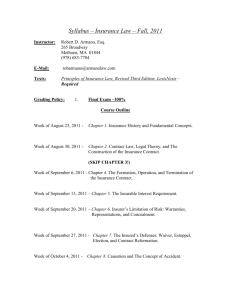

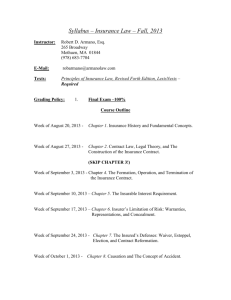

p42-4 insur oct07adl.qxd:p42-4 insur oct07adl.qxd 9/13/07 3:05 PM Page 2 The English and Scottish Law Commissions are continuing their work on the reform of insurance contract law. Sarah Turpin assesses the likely impact of their latest proposals. CONTRACT LAW THE LATEST T he law governing insurance contracts is outdated, complex and does not always favour the policyholder. The interests of the policyholder, which to date have received little attention from the legislature, are finally getting the attention they deserve. The English and Scottish Law Commissions are undertaking a detailed review of insurance contract law. In July, they published a joint consultation paper setting out their provisional proposals for reform in three specific areas: 1. misrepresentation and non-disclosure by the insured before the insurance contract is made 2. warranties and similar terms 3. cases where an intermediary or broker was wholly or partly responsible for pre-contract misrepresentations or non-disclosures. The aim behind the proposals is to ensure that the law ‘balances the interests of insured and insurer, reflects the needs of modern insurance practice and allows both insured and insurer to know their rights and obligations’. If this aim is to be achieved, there needs to be some further shifting of the scales in favour of the policyholder. Need for reform The current law derives many of its principles from the Marine Insurance Act 1906 which, despite its name, is generally understood to apply to all types of insurance. The Commissions have concluded that some of these principles do not meet ‘policyholders’ reasonable expectations’ and no longer suit a modern insurance market. This is not the first time such a conclusion has been reached. It has long been recognised that certain areas produce unexpected and unjust results for policyholders. As a result the current law has been adapted, particularly where consumers are concerned, by the introduction of non-binding statements of practice, FSA rules and the Financial Ombudsman Service (FOS) which applies a ‘fair and reasonableness’ approach to determine coverage disputes involving consumers. The problem is that there is no real consistency in approach, which results in unpredictability, particularly where consumers are concerned. Most busi- 40 StrategicRISK OCTOBER 2007 | www.strategicrisk.co.uk nesses are forced to rely upon the strict law, which, while in some respects more predictable, is heavily weighted in favour of the insurer. The proposed reforms will apply to all classes of insurance (and reinsurance) but deal separately with businesses and consumers. For consumers, a mandatory regime is proposed, based largely on the existing FOS guidelines. For businesses, the proposal is for a ‘default’ regime based on ‘accepted good practice’, which would apply in the absence of agreement to the contrary. There would also be protective measures for businesses which deal on the insurers’ standard terms. Misrepresentation & non disclosure The current law imposes a strict duty on the insured to disclose all material facts, and to avoid any material misrepresentations, prior to the inception of the policy. Most brokers are careful to highlight the disclosure obligation to their clients, and many insurers include warnings on their standard policy wordings. The problem is that, even if the insured is aware of the duty, the question of what is ‘material’ is determined with reference to what would influence the ‘prudent insurer’ when assessing the risk. How is the insured to predict what the ‘prudent insurer’ would regard as material? The other problem is that the remedy for breach of the duty is draconian. If the insurer can demonstrate that, if the information had been disclosed or not misrepresented, then it would not have written the policy (or would not have done so on the same claims had all relevant information been provided. The main feature of the mandatory proposals for consumer policyholders is abolition of their duty to volunteer information. The insurer would be under an obligation to ask questions to extract the required information and would not be entitled to avoid the policy for non-disclosure if the relevant question had not been asked. The duty on consumers would be to answer questions honestly and to take all reasonable care to answer questions accurately and completely. An insurer would have a remedy where it could show that the consumer made a misrepresentation which induced the insurer to enter into the contract (which is the requirement under the existing law), but the misrepresentation would have to be one which ‘a reasonable person in the circumstances’ would not have made. This shifts the test of materiality from that of the ‘prudent insurer’ to that of the ‘reasonable insured’. The remedy available to the insurer would depend upon the nature of the misrepresentation. If the misrepresentation was reasonable (or what is currently termed innocent) then there would be no remedy and the policyholder would be protected. If the misrepresentation was negligent (because the consumer should have known it was inaccurate and relevant) then the insurer would be granted a compensatory remedy. This would be designed to put the insurer in the position it would have been in had it known the true facts. If the misrepresentation was deliberate or reckless (because the consumer must have known it was inaccurate and that it mattered to the insurer) then the insurer would be entitled to avoid the policy. The proposal for business insureds is that the duty of disclosure should be maintained but modified. The proposed modification relates to the test of materiality. Business insureds would no longer be required to disclose what a ‘prudent insurer’ would want to know but only information that a ‘reasonable insured’ would recognise in the circumstances to be relevant. This is the default rule which would apply unless the parties agreed otherwise. The abolition of 'basis of contract' clauses is a welcome development terms), it is entitled to avoid the policy from inception. This is the case regardless of whether the nondisclosure or misrepresentation was fraudulent, negligent, or entirely innocent. It also makes no difference if the facts not disclosed or misrepresented have no relevance to, or connection, with any claims that have been made. The insurer is entitled to refuse all claims even if it would have paid such p42-4 insur oct07adl.qxd:p42-4 insur oct07adl.qxd 9/13/07 3:06 PM Page 3 INSURANCE The time has come to introduce a more level playing field addressing their mind to that of the ‘prudent insurer’. The fact is that, whatever the test, the insurer is clearly in the best place to determine what information is relevant to their assessment of the risk. There should therefore be greater onus on the insurer to ask the relevant questions required to extract that information, whether in the business or the consumer context. The Commissions clearly recognise that the remedy of avoidance has the effect of ‘over-compensating’ the insurer for the loss suffered. In the light of this, there seems to be no real justification for retaining avoidance as the default remedy where the non-disclosure or misrepresentation is merely negligent. It seems that some insurers have been arguing that the remedy should be retained on the basis that strong incentives are required to encourage businesses to act carefully with regard to their disclosure obligations. The same might of course be said of insurers ie that they should be given strong incentives to ask the right questions of their insureds to ensure that they extract all relevant information. Insurers have for too long had the comfort of knowing that, if they fail to extract all relevant information, they may have the option of avoiding the policy. The time has come to introduce a more level playing field. The avoidance remedy, given its harsh consequences, should be limited to circumstances where the non-disclosure/misrepresentation was deliberate or reckless. Warranties With regard to misrepresentations, the proposal is for a default regime similar to the scheme outlined above for consumers. The insurer would need to show that the business made a misrepresentation which induced the insurer to enter into the contract and which a ‘reasonable person’ in the circumstances would not have made. In other words, a business insured which acted honestly and reasonably should be protected from policy avoidance, unless of course the insurance contract provides otherwise. In terms of remedies, the Commissions invite views on whether the remedy of avoidance should be reserved for dishonest conduct, with a compensatory remedy being provided for negligent misrepresentation or non-disclosure, or whether the avoidance remedy should also be retained for the latter. The proposed modification of the test of materiality sounds good in principle but does it really solve the problem? In practice, the abolition of the ‘prudent insurer’ test should remove the need for expert evidence from an insurer, but how would the issue of what a ‘reasonable insured’ would regard as material be determined? Some critics have suggested that the only way a ‘reasonable insured’ would determine what was material would be by Warranties are promises of past, present or future facts. Under the current law, if a statement which is ‘warranted’ proves to be incorrect, the insurer is discharged from all liability under the policy and is entitled to reject all claims from the date of breach. This is the case regardless of materiality and regardless of whether the statement induced the insurer to enter into the contract. Where an insured gives a warranty as to future actions, such as the maintenance of a burglar alarm, any breach will discharge the insurer from liability, even for a claim which has no connection to the breach. Many insurers have adopted the practice of con- StrategicRISK OCTOBER 2007 | www.strategicrisk.co.uk 41 p42-4 insur oct07adl.qxd:p42-4 insur oct07adl.qxd 9/13/07 3:07 PM Page 4 INSURANCE There should be greater onus on the insurer to ask the relevant questions verting statements in the proposal form into warranties by means of a ‘basis of contract’ clause. This provides that any statements in the proposal form (and in any documents supplied with it) are incorporated into and form the basis of the contract. The legal effect of this apparently innocuous wording is to convert any statements in the proposal into warranties, breach of which discharges the insurer from all further liability. In the business context, this might include any statements in the financial accounts, copies of which are often provided to insurers with the proposal form. Few policyholders (whether consumer or business) understand the implications of these types of clause which, despite heavy criticism, are still in regular use. Proposals for warranties The proposal for consumers is that any statement of past or current fact should be treated as a representation rather than a warranty. Basis of contract clauses would also be abolished in the consumer context. This would mean that, if the consumer made an incorrect statement in the proposal form, the insurer would not be discharged from liability. The remedy available would depend upon whether the incorrect statement was made innocently, negligently or recklessly. For business insureds, warranties of past or present fact would still be permitted and liability would remain strict. In other words, it would not matter that the insured was unaware that the warranty was incorrect at the time it was given. The remedy for breach of these types of warranty would, however, be modified. The insurer would only be entitled to refuse any claims on the grounds of breach of warranty where it could be shown that the breach was material and had some connection to the loss. This would be the default regime and it would be open to the parties to agree other consequences if they wished. The parties would not, however, be entitled to convert all statements in the proposal form into warranties by means of a basis of contract clause. The contract would need to specify which facts were to be given warranty status. Warranties as to future facts, where consumers are concerned, should be enforced in accordance with existing FOS guidelines. These stipulate that an insurer may only refuse to pay a claim for breach of warranty if it has taken sufficient steps to bring the requirement to the consumer’s attention. If the consumer can prove on the balance of probabilities that the event or circumstance constituting the breach did not contribute to the loss then the consumer should be entitled to recover. 42 StrategicRISK OCTOBER 2007 | www.strategicrisk.co.uk For business insureds, the proposal is similar to that for consumers. If the business can prove that the event or circumstance constituting the breach did not contribute to the loss then the business should be entitled to recover. Unlike for consumer insurance, however, this would be the default rule and it would be open to the parties to agree other consequences. The remedy for a breach of warranty would be to enable the insurer to terminate cover for the future but the insurer would not be automatically discharged from liability. For standard term contracts, which are used in the business context but are not subject to negotiation, the insurer should not be permitted to rely upon a warranty if this would render the cover ‘substantially different’ from what the insured ‘reasonably expected’. This will depend in practice on how the insurer presented the policy to the insured. The abolition of ‘basis of contract’ clauses is a welcome development. The concern is, however, that insurers will rely heavily on their ability to contract out of the default regime, with the result that the proposed reforms will have limited benefit for business insureds. In practice, many business risks are placed on the basis of standard policy wordings drafted by insurers (with input from their lawyers), often with a view to taking full advantage of the legal remedies available to them. This is reflected in the fact that most standard policy wordings include a basis of contract clause. While the proposal is that standard policy wordings should be subject to ‘specific controls’, this will not actually prevent insurers from imposing warranties, nor from contracting out of the default regime, in their standard wordings. It will be up to the business insured to demonstrate that the insurer cannot rely upon such terms, in the event that a claim is rejected, on the basis that it would defeat their ‘reasonable expectations’ of cover. If the insurer can demonstrate that the insured knew about the term, and its implications, then the term would be upheld, even if the insured could demonstrate that it had no option other than to accept it. This is rather unsatisfactory from the point of view of the policyholder. Pre-contract information and intermediaries Under the current law, an insurance intermediary or broker is generally regarded as the agent of the insured rather than the insurer. This has important implications as, if the broker fails to disclose or misrepresents any facts prior to inception, that non-disclosure or misrepresentation will be attributed to the insured. This means that the insurer will be entitled to avoid the policy regardless of whether the insured provided the broker with the incorrect information. Thus, the insured bears responsibility for any mistakes made by the broker in relation to the presentation of the risk. The current proposal is that this should remain the position, for both consumer and business insurance, where the intermediary is clearly independent of the insurer and acting on the insured’s behalf. In other cases, the proposal is that an intermediary should be treated as acting for the insurer. This is more likely to apply in the consumer context and will not affect businesses who use brokers to search the market for them nor where the insured pays the broker a fee or commission. In the business context, these proposals are unlikely to have much impact, given that most large businesses instruct brokers to act as their own agents to search the market and negotiate the best cover available. The issue which is not addressed by the reforms, and which has recently aroused controversy, is the practice whereby brokers (despite being agents of the insured) are paid by the insurer. The next steps The Commissions are seeking responses to the provisional proposals by 16 November 2007. A separate consultation paper will be published in 2008 dealing with the remaining topics: post-contractual good faith, insurable interest and damages for late payment of claims. When the scope of the reforms has been decided, the Commissions will then consider how they should be implemented (whether by means of amendments to the 1906 Act or an entirely new Insurance Act) and whether there is a need to codify insurance law more generally. Sarah Turpin is associate in the insurance coverage practice group at Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis LLP, Tel: 0207 360 8285, E-mail: sarah.turpin@klgates.com K&L Gates will be submitting responses on behalf of policyholders and would welcome comments for inclusion. BACKGROUND In early 2006, the Commissions published a scoping paper which set out possible areas for reform (see earlier article Is the Tide Turning?, StrategicRISK June 2006). The Commissions have since produced several issues papers seeking further views which have led them to modify their proposals.