W Is Mutuality Viable? washington watch Some observations on the Massachusetts experience

advertisement

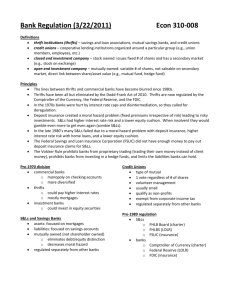

washington watch Is Mutuality Viable? Some observations on the Massachusetts experience e have all heard the naysayers— mutual thrifts are dinosaurs. They cannot access the capital markets and therefore are limited in their ability to grow and remain independent. Stock conversion, they say, gives the converted bank the incalculable advantage of capital to fuel greater growth and assure survival in difficult times. But is this really true? Mutually owned institutions that convert to stock-owned institutions seem less likely, not more, to remain independent than institutions that maintain their mutual charters. So we decided to do a little research on Massachusetts’s thrift banks between 1982 and 2004 to see what the facts really were. To find out what happened, we compiled information relating to all Massachusetts thrifts in existence in 1982, the year in which Massachusetts’s thrifts were first allowed to convert to stock. We tracked the deposit and asset growth of these thrifts (along with a new one chartered in 1985) from Oct. 31, 1982 to March 31, 2004. We also looked at what happened to these thrifts—whether they survived, failed or were acquired. Most of the conversions in Massachusetts occurred during the 1980s, shortly after the change in the law that permitted them. Since 1990 only 19 mutual thrifts in Massachusetts have converted to stock W by Stanley V. Ragalevsky and Sean P. Mahoney A thrift that remains mutual is poised to grow at strong and steady rates over the long term. The Mutual Advantage Perhaps the least surprising revelation was the low rate of survival for those banks that converted to stock. Of the 81 Massachusetts thrifts that converted to stock after Oct. 31, 1982 and before March 31, 2004 only 13 remain independent today. This represents a 16 percent “survival” rate (not including the two converted thrifts that announced plans to be acquired after March 31, 2004). February 2005 www.icba.org (including partial conversions) compared to the 62 thrifts that converted from 1983 to 1990. Comparing those banks that converted to those that remained mutual, we found that thrifts that remained mutual actually were more likely to remain independent; grew at stronger, steadier rates; and that size was not a good indicator of future independence. independentbanker 93 washington watch February 2005 But what was far more surprising was the ultimate acquirer of each one of those thrifts. Of the 67 thrifts that had converted to stock and were acquired, Bank of America purchased 25, while Citizens Bank of Massachusetts, Bank-North or Sovereign Bank ultimately acquired another 34. In fact, 59 of 67 acquired thrifts that had previously converted to stock were ultimately acquired by one of these four large banks, none of which was present in Massachusetts prior to 1982. One could say that the conversion of mutual thrifts in the 1980s and early 1990s was one factor that fueled consolidations and, in a sense, resulted in a privatization of a large portion of the mutual thrift industry in Massachusetts. By contrast, 73 percent of the mutual thrifts existing on Oct. 31, 1982 that remained mutual still exist as independent institutions today. The 49 mutual thrifts that were acquired by other banks were acquired by a more diverse group of acquirers, although Bank of America, Citizens Bank of Massachusetts, BankNorth and Sovereign ultimately acquired 19 of those thrifts through subsequent acquisitions. Growth Advantage We were also surprised to learn that since Oct. 31, 1982, the growth rate of mutual thrifts in Massachusetts has compared favorably to those mutual thrifts that converted to stock (and remained independent). The average deposit growth for thrifts that stayed mutual was 401 percent while the average asset growth was 429 percent. For thrifts that converted to stock, the average deposit growth was 393 94 independentbanker percent while asset growth was 504 percent. Thus, deposits grew at a slightly faster rate in thrifts that stayed mutual as opposed to thrifts that converted to stock. Assets grew faster for thrifts that converted to stock than for thrifts that remained mutual. Inherent in the mutual charter is a competitive advantage over publicly held stock thrifts. (Closely held stock thrifts may be a different story.) As a rule of thumb, a thrift that converts to stock and has publicly traded securities generally pays a dividend equal to about 35 percent of earnings. Investors expect such a return when they purchase stock in thrift. But a mutual thrift does not have to pay any dividends at all. As a result, each dollar of earnings increases capital by one dollar, which can be used to fuel further growth. By contrast, a thrift that pays 35 percent of its earnings as a dividend can only apply 65 cents of every dollar earned to capital. The compounding effect of paying a dividend over years takes its toll. The advantage of “free” capital is relatively easy to prove. Assume that a stock thrift and mutual thrift each have $100 million in assets and 8 percent capital in year one. Also assume that each thrift will have a return on assets of one 100-basis point (we did not discern any noticeable correlation between return on assets and whether the thrift was mutual or stock). After 20 years, the mutual thrift could maintain capital at 8 percent while growing to over $1 billion. By contrast, the stock thrift, which would pay 35 percent of its earnings as a dividend, would only grow to $477 million—less than half the size of its mutual counterpart—while maintaining capital at 8 percent. Size Not a Good Indicator We also looked at groups of the 20 largest thrifts, 20 smallest thrifts and the 20 median thrifts in Massachusetts on Oct. 31, 1982. We expected that the largest thrifts would be the most successful (that is, after all, one reason why we are so preoccupied with growth, isn’t it?). But only 20 percent of the 20 largest thrifts in 1982 still exist as independent institutions. By contrast, 40 percent of the smallest institutions in 1982 remain independent while 65 percent of the median institutions in 1982 remain independent. When we looked at aggregate deposit and asset growth (by percentage) over the past 22 years, some of the smaller institutions had some of the highest growth rates. Quality of management appeared to be a better indicator of future success than size. The Big Picture Mutual institutions can learn much from the experience of Massachusetts’s thrifts that converted to stock. The numbers are revealing. They show that if a mutual thrift converts to stock, the thrift’s chances of survival decrease drastically. It is almost certain that the thrift will eventually be acquired. Those thrifts that remain independent for a long time after converting to stock have had to struggle to maintain their independence. While a stock conversion may increase capital and fuel dramatic growth in the short term, a thrift that remains mutual is poised to grow at strong and steady rates over the long term. Thrift boards should consider these realities when making their strategic plans. Although it may be implied or www.icba.org many directors may assume it, it makes sense for the thrift’s strategic plan to assert the goal of staying independent. Remaining mutual is not the goal in and of itself—but mutuality as a stated business model furthers the institution’s goal of staying independent. If the institution is serving its community and filling a vital role in the local economy, shouldn’t the board be committed to keeping the institution independent? What value is delivered to a thrift’s community by rapid growth if the thrift will soon be absorbed by a mega-bank? For some institutions the decision to remain mutual requires little deliberation while for others, it is a matter for serious debate. Sometimes banks have no choice but to convert to stockholder-owned institutions. Obviously, the decision that a conscientious thrift board of directors makes to convert from mutual to stock form is a difficult one. In any event, it is important that the thrift’s board of directors retains that flexibility to make that decision for the institution. But as the experience in Massachusetts shows, mutuality is a valid business model that is still relevant and viable in the 21st century. Notwithstanding the turbulent period of 1985 to 1995 and the many economic crises that preceded it, mutual thrifts have not only survived, but have thrived. ib www.icba.org February 2005 Stanley V. Ragalevsky is a partner and Sean P. Mahoney is an associate in the Boston law office of Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Nicholson Graham LLP. independentbanker 95