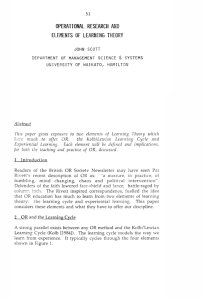

A comparison between two methods of teaching social studies at... by Melvin William Roe

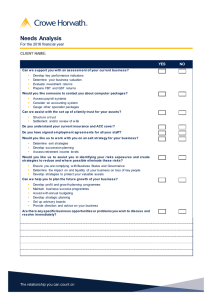

advertisement