Evaluation of Federal grazing permits on Montana cattle ranches

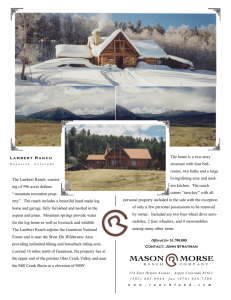

advertisement