Cheating behaviors of college students by Kathryn Louise Holleque

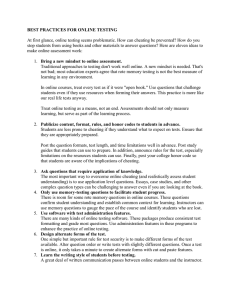

advertisement