EXPLORING THE IMPLEMENTATION OF NEW PUBLIC SERVICE ROLE WITHIN DISASTER MANAGEMENT Andrew T. Ranck

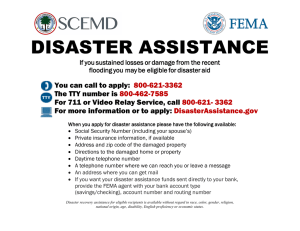

advertisement