THE INTEGRATION OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE ARTS, SCIENCE AND OTHER

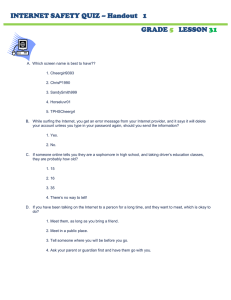

advertisement