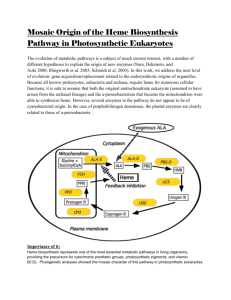

THE MECHANISM OF HEME TRANSFER FROM THE STREPCOCCAL CELL

advertisement