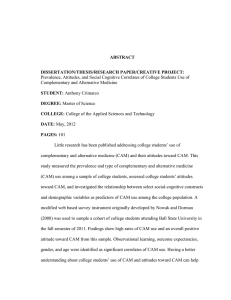

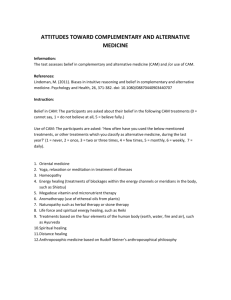

AN ASSESSMENT OF HEALTH LITERACY ABOUT COMPLEMENTARY AND

advertisement