Restorative Design Thesis: Architecture in Chandigarh, India

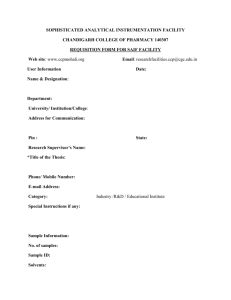

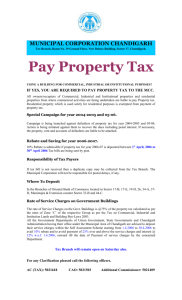

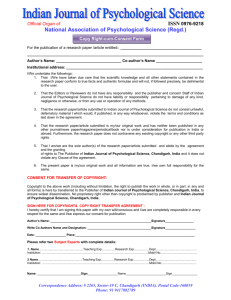

advertisement