INPATIENT SUICIDE IN THE GENERAL MEDICAL SETTING: AN INTEGRATIVE LITERATURE REVIEW by

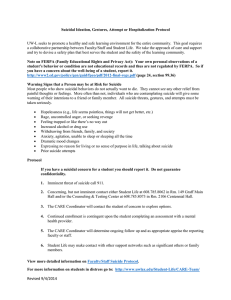

advertisement