UNDERSTANDING THE EXPERIENCES OF POSTSECONDARY FACULTY AND STUDENTS WITH PRECISION TEACHING:

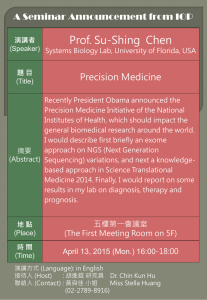

advertisement