THE POWER AND POTENTIAL OF PERFORMATIVE DOCUMENTARY FILM by

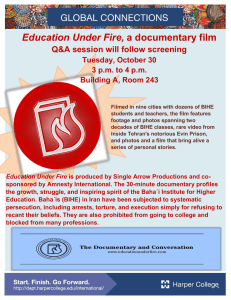

advertisement