Document 13464046

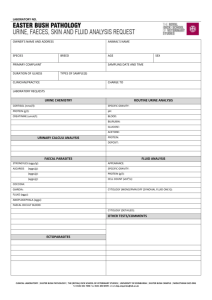

advertisement