Treasury Secretary Outlines Revised TARP Strategy Revised TARP Strategy

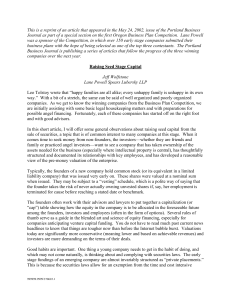

advertisement