Hydrological modeling of outflow channels and chaos regions on Mars

advertisement

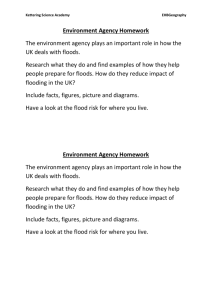

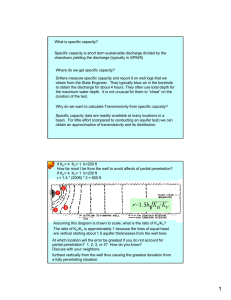

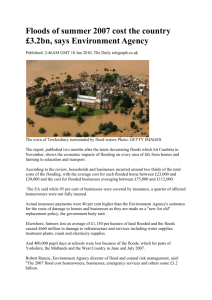

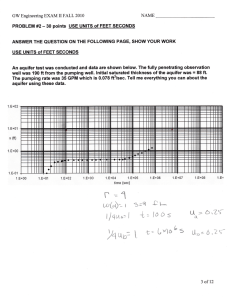

Click Here JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 112, E08001, doi:10.1029/2006JE002881, 2007 for Full Article Hydrological modeling of outflow channels and chaos regions on Mars Jeffrey C. Andrews-Hanna1,2 and Roger J. Phillips1 Received 15 December 2006; revised 6 March 2007; accepted 11 May 2007; published 2 August 2007. [1] The Martian outflow channels were carved by the eruption of catastrophic floods from groundwater aquifers. This study models the time evolution of a typical outflow channel flood originating within a chaos region. The flood initiates when superlithostatic pore pressures within a confined aquifer lead to the propagation of hydrofractures through the confining cryosphere to the surface. The peak discharges are modulated by diffusion of the flood pulse within the chaos region, resulting in a rapid rise in discharge immediately after flood initiation. Later flow is limited by diffusion through the aquifer and is sensitive to the variation of the hydraulic properties with changing pore pressure. After the termination of the flood by freezing within the chaos region much of the aquifer remains pressurized. Diffusion of the excess pressure from the undrained portions of the aquifer back toward the chaos region triggers a second flood, ultimately resulting in a periodic series of floods. For Iani Chaos at the source of Ares Valles, modeled peak discharges on the order of 106 to 107 m3 s1 were obtained, with total volumes of individual floods ranging from 600 to 5000 km3 and a minimum period between successive floods of 44 years. The cumulative flood volume depends upon the number of floods, which is a function of the volume of pressurized aquifer or the duration of recharge from distant sources. These results suggest that individual channels were likely carved by large numbers of floods and were unlikely to have experienced bankfull flow in their final state. Citation: Andrews-Hanna, J. C., and R. J. Phillips (2007), Hydrological modeling of outflow channels and chaos regions on Mars, J. Geophys. Res., 112, E08001, doi:10.1029/2006JE002881. 1. Introduction [2] The circum-Chryse outflow channels (Figure 1) record the largest and most dramatic flooding events observed in the Solar System. The channels were discovered in Mariner 9 images, which revealed enormous fluvial features tens to hundreds of kilometers across, a kilometer or more deep, and hundreds to thousands of kilometers in length [Baker and Milton, 1974]. The outflow channels date primarily from the Hesperian epoch (3.7 to 3.0 Ga [Hartmann and Neukum, 2001]) [Baker, 1982], after a dramatic cooling of the climate led to the growth of a thick cryosphere [Carr, 1996a]. A number of features within these channels, such as streamlined islands and deep scour marks, are indicative of the catastrophic flow of water [Baker, 1979, 1982]. The immense scale of the channels is made even more enigmatic by the fact that the individual outflow floods apparently emerged fully formed from the ground at discrete sources. Most outflow channels originate either from a broad region of disrupted terrain, referred to as a ‘‘chaos region,’’ or from within a tectonic canyon. The chaos-sourced channels are thought to have formed through the catastrophic eruption of water directly from a pressurized 1 McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences and Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri, USA. 2 Now at the Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA. Copyright 2007 by the American Geophysical Union. 0148-0227/07/2006JE002881$09.00 groundwater aquifer trapped beneath the thick confining cryosphere [Carr, 1979, 1996a], while the canyon-sourced channels have been interpreted as evidence of the overtopping and catastrophic drainage of an enclosed canyon lake that had been filled by groundwater [Robinson and Tanaka, 1990]. [3] Most studies of the outflow channels have focused on interpretations of the surface geomorphology, applying our understanding of the hydraulics and fluvial geomorphology of terrestrial floods to the Martian outflow channels. The individual outflow floods have been estimated to have total volumes of up to 106 km3 of water [Rotto and Tanaka, 1992] and peak discharges, assuming bankfull conditions, approaching 109 m3 s1 in some cases [Komatsu and Baker, 1997]. These discharges are approximately 7 orders of magnitude greater than the largest terrestrial groundwater springs, and 2 orders of magnitude greater than the largest catastrophic floods on the Earth [Baker, 1982]. However, these estimates commonly rely upon a number of assumptions that have not been adequately tested, including the assumption that the channels formed in single events and experienced bankfull flow in their current state. Mapping studies have delineated the relative erosional histories of the main circum-Chryse channels [Nelson and Greeley, 1999], but the detailed history of flooding within the individual channels remains poorly understood. [4] We take a different approach, and attempt to model numerically the formation and evolution of the outflow channel floods at their sources in regions of chaotic terrain. E08001 1 of 14 E08001 ANDREWS-HANNA AND PHILLIPS: MARTIAN OUTFLOW CHANNEL FLOODS E08001 diameter of 10 cm, thus assuming that the majority of the sediment was composed of cobbles and boulders and likely underestimating the carrying capacity. Clearly, large uncertainties remain in the flood volumes required to carve the outflow channels. Nevertheless, the simple approach of assuming a maximum sediment load provides a reasonably firm lower limit on the flood volumes and a valuable constraint for hydrologic modeling. [6] The peak discharges are commonly estimated by applying the Chezy-Manning equation [Knighton, 1998] scaled to Mars gravity: 1 gMars 1=2 Q ¼ w d 5=3 S gEarth n Figure 1. Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA) shaded relief map of outflow channels in the circum-Chryse region. Beginning with the a priori assumption of a pressurized aquifer, we utilize a hydrological model of the Martian megaregolith [Hanna and Phillips, 2005] combined with a model of flow through the chaos region in order to simulate the flow of water through the aquifer to the surface at the flood source, so as to reconstruct the evolution of the discharge and flood volume as a function of time. We take Iani Chaos at the source of Ares Valles as our case study of a typical chaos outflow source. Using the insight gained into the nature of the floods, we then reconsider some of the basic assumptions of the geomorphic studies based on our model results. In particular, we focus on the implications of the model results for the number, duration, evolution of discharge, and erosional history of the outflow channel floods. 2. Previous Studies 2.1. Fluvial Geomorphology [5] Previous estimates of the volumes and peak discharges of the floods came from interpretations of the channel geomorphology. Flood volume estimates were calculated from the measured channel volumes by assuming a maximum volumetric sediment load, above which turbulent flow is no longer possible and the flood will become a debris flow, and calculating the volume of sediment-laden water required to remove the requisite volume of rock [Carr, 1987; Komar, 1980; Rotto and Tanaka, 1992]. Assuming a volumetric sediment fraction of 0.4, this method yields total flow volumes for the individual outflow channels of approximately 105 to 3 106 km3. However, this assumed sediment load serves only as an upper limit, and thus provides a lower limit on the flood volume. Plausible sediment loads could range from values typical of terrestrial rivers, on the order of 0.001, up to this upper limit of 0.4, leaving an uncertainty of a factor of 400. Recent work has emphasized the likelihood of much lower sediment loads than those typically assumed [Kleinhans, 2005]; however, that study assumed that only the bed load was significant, thus ignoring the significant capacity of the floods to carry suspended loads. Furthermore, sediment load calculations were done using a median sediment particle ð1Þ where Q is the discharge, n is the roughness coefficient (typically taken to be in the range of 0.015 to 0.035 [Robinson and Tanaka, 1990]), w is the channel width, d is the channel depth (assumed to be much less than the width), S is the hydraulic slope (commonly taken to be the bed slope), and g is the acceleration of gravity. More recently, Wilson et al. [2004] argued that the Darcy-Weisbach equation more accurately represents the mean flow velocity and discharge: Q ¼ w d 3=2 ð8gMars S=fc Þ1=2 ð2Þ where fc is the friction factor, which depends primarily on the nature of the channel bed and the ratio of the bed roughness elements to the flow depth. [7] It can be seen in equations (1) and (2) that the discharge scales with either the 5/3 or the 3/2 power of the flow depth, though there is an additional dependence on depth in the friction factor in equation (2). For the Martian outflow channels, we have no way of measuring the depth of flow at the time of peak discharge. It has commonly been assumed that the channels in their present configuration were bank full during their final stage of flow [e.g., Komatsu and Baker, 1997], though more recent studies have considered the likelihood that channel flow was less than bank full [Mitchell et al., 2005] based on the observation of small inner channels within some of the outflow channels [Williams et al., 2000; Williams and Malin, 2004; Leask et al., 2007]. Typical maximum discharge estimates based on the bankfull assumption are on the order of 108 to 109 m3 s1 for Ares Valles [Komatsu and Baker, 1997]. The sensitivity of the discharge to the flow depth introduces a significant degree of uncertainty into the estimations of the discharge. The calculation of the channel discharge is complicated further by the observation of level or even uphill slopes along the channel beds in the downstream direction for distances of hundreds of kilometers [Williams and Phillips, 1999; Skinner and Tanaka, 2000], leading to zero or negative discharges by simple application of equations (1) and (2), and calling into question the reliability of any discharge estimate based on channel slope and cross section. [8] An added complication arises from the fact that the friction factor used in equation (2) is generally taken from empirical expressions based on terrestrial channel observations, which are parameterized in terms of the flow depth and the channel bed roughness. However, analytical expressions for the friction factor demonstrate its dependence on 2 of 14 E08001 ANDREWS-HANNA AND PHILLIPS: MARTIAN OUTFLOW CHANNEL FLOODS the Reynolds number, which is a function of the flow depth, fluid density, and viscosity. The high concentrations of suspended sediment and ice commonly invoked for the Martian outflow channels would result in significant changes to the density and viscosity. For example, the maximum volumetric sediment load of 0.4 would increase the viscosity by a factor of 16 [Bargery et al., 2005] and the density by a factor of 2. If we simply assume that the dependence of the friction factor on flow depth [Wilson et al., 2004] reflects its dependence on the Reynolds number, the resulting effect would be to decrease the discharge for a given flow depth by 33%. However, since both the actual sediment load and the dependence of the friction factor on the Reynolds number are poorly constrained, we do not attempt to correct for this effect in our calculations. [9] These shortcomings in the quantitative geomorphology approach to studying the outflow channels are discussed not to discount the usefulness of such approaches, but rather to suggest that caution must be taken with respect to the application and interpretation of these methodologies. The goal of this study is to supplement such geomorphic approaches through the use of numerical models of the outflow channel floods at their sources, and thereby gain insight not only into the properties of the floods at the surface, but also the subsurface processes driving their formation. 2.2. Modeling Studies [10] In a seminal study, Carr [1979] modeled the discharge of an outflow channel source region using the onedimensional hydraulic well approximation of Jacob and Lohman [1952], assuming spatially and temporally uniform aquifer properties. The chaos source region was represented as a cavity extending through both the confining layer and the aquifer to the impermeable basement beneath, a geometry that may be more representative of the canyon sourced outflow channels. It was found that peak discharges comparable to those inferred for the outflow channels could be generated by flow through the aquifer. However, the peak discharges occurred at the onset of the floods and then decreased with time as a power law, implying that the maximum discharges would have been short-lived and would have coincided with the earliest immature channel. This early peaking of the discharge clearly has implications for the validity of the assumption that the channels in their final form could ever have been bank full [Wilson et al., 2004], an issue that we will address in light of this study in a later section. [11] More recently, Carr [1996b] suggested that the floods are not limited by the permeability, but rather are able to achieve high discharges by the disruption and entrainment of the aquifer materials themselves, thus circumventing the gradual diffusion of pore pressures through the aquifer. However, we note that the water to rock ratios in typical aquifers (1:9, assuming a porosity of 0.1) are much lower than the minimum water to rock ratio in the floods (3:2, assuming a maximum volumetric sediment fraction of 0.4). Thus, in order to disrupt and entrain the aquifer host material in the floods, the pore water contained within the disrupted aquifer could constitute at most 7% of the total floodwater, with the remainder being supplied by diffusion through the intact aquifer. Alternately, erosion and removal E08001 of the outermost drained portions of the aquifer could increase the hydraulic gradient in the remaining aquifer, but the flood would still be diffusion limited. We further note that the volumes of water inferred to be necessary to carve the channels greatly exceed the volume of water that can be contained in the aquifers underlying their sources, thus requiring disruption and removal of an aquifer of much greater extent than the observed chaos regions. [12] Several more recent works have modeled the outflow channel sources under the assumption that the flow through the aquifer was driven by a uniform hydraulic gradient that was related to the observed regional topographic slope [e.g., Head et al., 2003]. This approach assumes implicitly that the outflow channels were driven by steady flow through the aquifer in equilibrium with a constant recharge at distance, in conflict with the understanding of the floods as the product of the catastrophic drainage of a highly pressurized aquifer. Manga [2004] recognized this, and demonstrated the importance of the time variation of the flow from a pressurized aquifer for channels originating within linear tectonic sources. [13] We here build upon the existing body of work by simulating the origin of outflow channel floods within chaos regions, using the hydrological model of Hanna and Phillips [2005] and taking into account the variation of the hydraulic parameters with depth and pore pressure. This study sheds new light on the initiation and termination of outflow channel floods, the nature of the flow through the source aquifers, the number and duration of the floods, the variation of the discharge and total flood volume with time, and the erosive history of the channels. 3. Hydrological Model 3.1. Model Overview and Constraints [14] We take the existence of a pressurized aquifer as an a priori condition, and focus on the evolution of the discharge from such a pressurized aquifer at a chaos source. We model the flow of water to the surface as it passes through both the aquifer (section 3.2) and the disrupted confining layer in the chaos region (section 3.3). Section 3.4 considers the minimum discharge that can be maintained against freezing, which ultimately causes the termination of the floods. The implementation of the model and its specific application to Iani Chaos and Ares Valles are discussed in section 3.5. [15] While the results of this study can be applied to any chaos-sourced outflow channel, we tailor the model to apply to Iani Chaos, at the source of Ares Valles, allowing us to compare the model results with the geomorphic estimates of the discharge and flood volume for this channel. Iani Chaos has an area of 1.5 105 km2, corresponding to an effective radius of approximately 200 km in a cylindrically symmetric model. The chaos region is drained by Ares Valles, with a channel depth of approximately 1 km, width of 20 km, and average bed slope from Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter topography [Smith et al., 2001] of 0.001. As discussed previously, the discharge of Ares Valles under bankfull conditions has been estimated to be approximately 108 to 109 m3 s1 [Komatsu and Baker, 1997], though values several orders of magnitude lower are possible for more conservative flow depths. The total channel volume of Ares Valles is estimated at approximately 8 104 km3 [Carr, 3 of 14 E08001 ANDREWS-HANNA AND PHILLIPS: MARTIAN OUTFLOW CHANNEL FLOODS E08001 ity are calculated on the basis of the inferred abundance of breccia and fractures, and on the known properties of terrestrial and lunar analogues to these materials. The permeability in this model under hydrostatic pore pressures ranges from 1011 m2 at the surface, down to 1015 m2 at depths greater than 5 km, while the compressibility ranges from 2 109 to 1.5 1010 Pa1. All of the hydraulic properties are highly sensitive to the effective stress state of the aquifer as determined by the combination of the lithostatic pressure and the fluid pore pressure. For example, as the pore pressure increases, the fracture apertures widen, resulting in an increase in the permeability, which depends on the cube of the aperture width. This pore pressure dependence will be particularly important for the outflow channels, in which large and rapid variations in the pore pressure during the drainage of the aquifer are expected. Figure 2. MOLA shaded relief map of Iani Chaos (centered on 342°E, 0°N). 1987], corresponding to a minimum total flow volume of 1.2 105 km3 for a maximum volumetric sediment load of 0.4. However, Ares Valles has four major sources, including Iani, Margaritifer, and Aram Chaos regions, as well as a drainage system flowing northward from the Argyre basin. Assuming that one quarter of the flood volume originated from Iani Chaos, this leaves a minimum volume of 3 104 km3 of water. Again, we emphasize that this estimated flood volume is only an extreme lower limit. 3.2. Aquifer Model [16] Transient flow within an aquifer is governed by the diffusion equation [Domenico and Schwartz, 1990]: @h 1 r ðkrhÞ ¼ @t m nbw þ bpore ð3Þ where h is the hydraulic head (m), k is the spatially and temporally variable intrinsic permeability of the aquifer (m2), m is the fluid viscosity (Pa s), n is the porosity, b w is the compressibility of water (Pa1), and b pore is the compressibility of the aquifer matrix. The hydraulic head is a potential term, which includes both the elevation z of a fluid parcel above a datum, as well as the aquifer pore pressure Ppore: h¼ Ppore þz rw g ð4Þ where rw is the density of water. Thus the hydrological model must specify the porosity, permeability, and compressibility of the aquifer materials. [17] The outflow channel source regions occur primarily within the Noachian aged crust and Hesperian volcanics east of Tharsis. We adopt the megaregolith aquifer model of Hanna and Phillips [2005], which assumes a thick regolith overlying the fractured and partially brecciated basement rock beneath. The porosity, permeability, and compressibil- 3.3. Chaos Model [18] There is a wide range in chaos region morphologies on Mars. On one end of the spectrum, chaos regions such as Aromatum Chaos at the head of Ravi Valles show clear evidence of tectonic or structural control, and also seem to have experienced significant collapse of the subsurface [Leask et al., 2004]. This morphology suggests both strongly heterogeneous and likely anisotropic subsurface properties, as well as dramatic changes to the surface and subsurface structure during the course of the flooding. At the other end of the spectrum, chaos regions such as Iani Chaos at the head of Ares Valles manifest themselves in the form of distributed fractures and fissures over a broad region, with no clear evidence for either collapse or tectonic control. While both types of chaos are important in understanding the nature of outflow channel flood generation, and there are undoubtedly similarities in the processes involved in the flooding from both, the latter is much more amenable to the modeling approach of this study. [19] As stated earlier, it is generally thought that chaos regions at the sources of outflow channels formed when the fluid pore pressure within a confined aquifer reached or exceeded the lithostatic pressure at the base of the cryosphere [Carr, 1979]. At this time, the excess pore pressure would expand the fractures within the aquifer and allow their propagation into the frozen crust above. If the outflow channels formed under cold climate conditions similar to those that prevail on the planet today, these fluid filled fractures would need to propagate through a cryosphere thickness of 1 to 3 km, assuming a surface temperature of 220 to 250 K, a thermal conductivity of 2 to 3 W m1 K1, and a heat flux of 50 mW m2 [Hauck and Phillips, 2002]. This flow from the aquifer to the surface through the chaos region has a diffusive effect on the flood pulse in the early stages of flow, as will be demonstrated in the sections that follow. [20] In order to construct a hydrological model of the chaos region, we first look at the structure within and around Iani Chaos (Figure 2). Toward the periphery of the chaos region, isolated and branching flat-floored valleys penetrate the surrounding undisrupted surface. These valleys appear to be structurally controlled, and are likely the surface manifestations of fractures. Within the main chaos region, the valleys intersect and increase in number, 4 of 14 E08001 ANDREWS-HANNA AND PHILLIPS: MARTIAN OUTFLOW CHANNEL FLOODS Figure 3. Wide- and narrow-angle Mars Orbiter Camera (MOC) images of a fissure (arrows) between mesas in Hydraotes Chaos (MOC images M09-03791 and M0903790, left and center, respectively). A portion of the narrowangle MOC image (white box) has been enlarged at right. dissecting the surface into a large number of flat-topped mesas of relatively undisturbed country rock. These mesas range in size from approximately 1 to 10 km across. Most of the intermesa valleys have flat smooth floors, presumably because of erosional widening and infilling with sediments and debris. In places, however, it is possible to see the bedrock structure at the base of these valleys, in which the surface trace of a fissure that parallels the mesa walls can be seen (Figure 3, in nearby Hydraotes chaos). We propose that these fissures are in fact the hydrofractures that served as conduits for the flow in the outflow channel events. While the valleys between mesas have widths on the order of 1 km, and the surface manifestations of these fissures have widths on the order of 100 m, the actual subsurface conduits were likely much smaller than their eroded surface manifestation. [21] Over much of the chaos area, the mesas grade into regions of more heavily disrupted terrain with a hummocky appearance, in which rounded hills are separated by flat, dune-filled valleys with a spacing ranging between a few hundred meters and 1 km (Figure 4). The outlying linear valleys, mesas and hummocky terrain appear to be members of a continuum, with the hummocky terrain representing the eroded remnants of hydrofracture-bound mesas. The difference in appearance is attributed to the closer spacing of the hydrofractures in the hummocky terrain, which would result in both a smaller lateral extent of the mesas, as well as a greater flux of water to the surface and increased erosion. [22] We envision the following scenario for chaos formation. In the initiation of the outflow event, hydrofractures begin to propagate upward through the cryosphere from the aquifer beneath. Rather than propagating new fractures through solid rock, it is more likely that existing icecemented fractures within the cryosphere will be activated and used as conduits for flow to the surface. These randomly oriented fluid filled fractures will intersect and coalesce as they propagate upward, similar to patterns of magma migration [Hart, 1993]. To a first approximation, the spacing of the hydrofractures when they reach the surface should be comparable to the thickness of the cryo- E08001 sphere through which they have propagated, to within a factor of order unity, depending on the statistical distribution of fracture orientations. Thus the typical valley spacing within the chaos region, and by inference the surface hydrofracture spacing, of 1 km is in agreement with the expected cryosphere thickness of 1 to 3 km. [23] The hydrological properties of the chaos region are based on the inferred spacing and width of the hydrofractures. We make the simplifying assumption of a uniform hydrofracture spacing with depth, with a spacing of 1 km based on surface observations. Observations of terrestrial faults and hydrofractures suggest widths in the range of 104 to 9 103 m are typical immediately after a faulting or hydrofracturing event [Gudmundsson et al., 2001], much greater than the typical preexisting fracture width within the aquifer of 1 –2 104 m [Hanna and Phillips, 2005]. However, the large and sustained flux of water through the chaos region hydrofractures would likely lead to some degree of erosional widening. We consider a range of hydrofracture apertures of 5 103 to 5 102 m. While this model is a gross oversimplification, it will later be seen that the resistance to flow within the chaos region is significantly less than that in the aquifer, such that the hydraulic properties of the chaos region do not significantly impede the flow except during the initial flood pulse, and do not affect the flow hydrograph at later times. [24] Thus flow occurs within two types of fractures on its path to the surface: water within the aquifer passes through the narrow-aperture fractures and joints that permeate the crust; while water within the chaos region passes through freshly generated macroscopic hydrofractures. While flow within the narrow-aperture fractures within the aquifer will be laminar, the flow will become turbulent as it is focused into the wider chaos hydrofractures draining to the surface. Flow through a conduit in the turbulent regime is modeled as [Head et al., 2003] q¼ 1=2 g wfiss rh wfiss Nfiss fw ð5Þ Figure 4. MOC narrow-angle image of rounded hills in the hummocky terrain within Iani Chaos (portion of MOC image E01-00637, centered on 341.6°E, 4.1°S). 5 of 14 E08001 ANDREWS-HANNA AND PHILLIPS: MARTIAN OUTFLOW CHANNEL FLOODS where q is the discharge (m s1), g is the acceleration of gravity, wfiss is the fissure width (m), fw is the dimensionless friction factor (here taken to be 0.025 for a water filled fracture [French, 1985]), and Nfiss is the spatial number density of fissures (m1). Note that the discharge is now proportional to the square root of the gradient in hydraulic head, and so the conventional concept of permeability does not apply. Time-dependent flow through the chaos region is solved for by balancing the divergence of the flow with the change in hydraulic head: @h 1 rq ¼ @t rw g nbw þ bpore " # 1=2 g wfiss 1 r ¼ rh wfiss Nfiss fw rw g nbw þ bpore [27] The transition from turbulent to laminar flow conditions for pipe flow occurs for critical Reynolds numbers Recr of 2000 to 4000 [Tritton, 1988]. For flow through a conduit, the Reynolds number is calculated as Re ¼ 3.4. Flood Termination [25] Since the discharge to the surface is limited by the diffusion of the water through the aquifer, it is expected that the discharge will decrease with time as a power law, as found by Carr [1979]. In the waning stages of the flood, the flow would no longer be maintained against freezing in the cold Martian climate, and would be terminated. Clow [1994] assumed that the flood is limited by freezing within the channel and estimated the minimum discharges that could be maintained for conditions appropriate for the outflow channels under the present climate to be on the order of 100 m3 s1, though the actual value will depend on the slope and channel geometry. However, terrestrial experience demonstrates that rivers that freeze to their bottom do not cease flowing, but rather break out through the ice layer upstream of the constriction and flow across the top of the ice, building up thick deposits of overflow ice or aufeiss in the process. For the outflow channels, freezing of the channel downstream of the chaos region cannot affect the flow through the aquifer and its release to the surface, and thus is not an effective means of terminating the floods. [26] Alternatively, we suggest that the limiting factor in the termination of the floods is the freezing of the water within the chaos region hydrofractures. In order to reach the surface, the aquifer water must pass through the cryosphere thickness of 1 to 3 km within a network of narrow conduits. Throughout this transit, the water will lose heat conductively to the surrounding cryosphere, which ranges in temperature from 273 K at its base to approximately 220 K at the surface for the present-day climate. Under conditions of turbulent flow, the conductive heat loss will result in the formation of suspended frazil ice particles [French, 1985] which can remain in the flow and be advected out of the system to the surface, allowing the flow to be maintained against freezing. However, as the discharge wanes and the flow in the chaos region becomes laminar, the conductive heat loss will result in the nucleation of ice directly onto the hydrofracture walls, and the conduits will rapidly freeze shut. wfiss ur m ð7Þ where u is the average flow velocity. The critical Reynolds number can be used in (7) to calculate the critical flow velocity, ucr, and discharge, Qcr, from the chaos region as a whole at the point at which flow to the surface becomes laminar: ð6Þ Expansion or contraction of these wide-aperture hydrofractures proceeds at the expense of the surrounding rock mass, and thus a compressibility of 1010 Pa1 is assumed, representative of fractured bedrock or ice cemented regolith. E08001 Qcr ¼ ucr wfiss Achaos Nfiss m Achaos Nfiss ¼ Recr r ð8Þ where Achaos is the area of the chaos region, and Nfiss is the typical hydrofracture density in the chaos region (m1). Note that the dependence upon the actual hydrofracture width drops out of the final form of equation (8), thereby removing the least constrained parameter from the equation. For a 200 km radius chaos region with a typical hydrofracture density of 103 m1 (typical spacing of 1 km), a water viscosity of 103 Pa s, and a critical Reynolds number of 2000, we calculate a minimum discharge of 2.5 105 m3 s1. The increased turbulence resulting from the roughness of the hydrofracture walls and the advection of heat from deeper portions of the aquifer may delay the termination of the flood, so we consider minimum discharges of 104 to 105 m3 s1. When the discharge decreases to this level, the flow through the chaos region hydrofractures will become laminar and the conduits will become choked with ice, thereby terminating the flood. Smaller chaos regions will have proportionately lower minimum discharges. This approach results in a higher cutoff value for the discharge than estimated by Clow [1994], precluding the long period of sustained low-level flow that would otherwise ensue. This result is in agreement with the observation that the outflow channels are dominated by catastrophic erosional landforms, with little evidence for extended periods of later, lower energy flow. Smaller inner channels consistent with low discharge latestage flow are observed in some of the outflow channels [Williams et al., 2000; Williams and Malin, 2004], but do not appear to dominate their erosive history. 3.5. Model Implementation [28] Flow is modeled using a fully explicit, two-dimensional, finite difference model to solve equations (3) and (6) on an axisymmetric nonuniform mesh representing a cylindrically symmetric chaos region underlain by a laterally extensive aquifer subject to no-flow conditions at the top (beyond the chaos region), bottom, and edge (beyond the hydraulic influence of the flood event). We represent Iani Chaos as a 200 km radius chaos region in a 1 to 3 km thick cryosphere, with a hydrofracture spacing of 1 km and hydrofracture widths ranging from 5 103 to 5 102 m. The base of the aquifer is set at 20 km depth, and its hydrological properties are modeled after Hanna and Phillips [2005]. We 6 of 14 E08001 ANDREWS-HANNA AND PHILLIPS: MARTIAN OUTFLOW CHANNEL FLOODS Figure 5. Discharge as a function of time in the early stages of a flood from a 200 km radius chaos region for different cryosphere thicknesses and aquifer overpressures (baseline model represented by the solid line), as well as for a model in which the permeability and compressibility of the aquifer are held constant in time. also consider the possibility of greater fracture apertures by a factor of two within the aquifer. The model mesh extends out to a distance of 2000 km from the chaos region center, well beyond the hydraulic influence of the discharge and aquifer depressurization at the chaos region. After each time step, the aquifer properties are updated to reflect their dependence upon the changing hydraulic head. For initial conditions, we assume a uniformly pressurized aquifer, such that the pore pressure at the base of the cryosphere exceeds the lithostatic pressure by an amount ranging from 2 to 10 MPa. The exact threshold for outflow channel initiation is unknown, and will depend upon the material properties of the confining layer and the details of the flood onset. Hydrofractures can begin to propagate once the pore pressure reaches the lithostatic pressure, but the rate of propagation must be sufficient to prevent freezing of the fluids within, suggesting pore pressures in excess of the lithostatic pressure are likely required. We note that 10 MPa is comparable to the tensile strength of basalt [Peck and Minakami, 1968], and so pore pressures greater than this are unlikely. Flooding is initiated by applying a constant head boundary condition to the top of the chaos region, set equal to the surface elevation, thus allowing the pressurized aquifer to drain to the surface through the chaos hydrofractures. The flood continues until a minimum discharge is reached, here assumed to be between 104 and 105 m3 s1. 4. Model Results 4.1. Individual Floods [29] We first look at the model results for individual outflow channel floods, turning later to the possibility of repeating floods. The discharge at the surface as a function of time for the early stages of flow is shown in Figure 5 for our baseline model, assuming a 20 km thick aquifer overlain by a 2 km thick cryosphere, a pore pressure excess of 5 MPa E08001 above the lithostatic pressure, and an assumed hydrofracture width in the chaos region of 5 103 m. Also shown are a simulation with a 1 km thick cryosphere, and a simulation with an excess pore pressure of 2 MPa. The peak discharge for the baseline model of approximately 7.6 106 m3 s1 is reached after an elapsed time of 2.4 104 s (6.7 hours) after outflow initiation. The discharge drops quickly after the peak value is reached. The minimum discharge of 105 m3 s1 is reached after 2.1 106 s (23 days), at which point a total flood volume of 1.0 103 km3 has been debauched. Alternatively, if a minimum discharge of 104 m3 s1 is assumed, the flood terminates after 3.6 107 s (417 days) after having released 1.8 103 km3 of water to the surface. Thus decreasing the minimum discharge results in a dramatic increase in the duration of the flood, but only a modest increase in the total flood volume. [30] The results from model runs for a variety of aquifer parameters and initial conditions are given in Table 1. Peak discharges range from 8.2 105 to 1.6 107 m3 s1, and flood volumes range from 614 to 2850 km3. For different sized chaos regions, the peak discharges will scale linearly with the area, while the total flood volumes will scale nearly linearly. The results show that higher peak discharges are possible for greater chaos hydrofracture widths, though there is a tradeoff between the magnitude and the duration of these peak values. Increasing the cryosphere thickness results in a decrease in the peak discharge due to the greater diffusion of the flood pulse through the thicker cryosphere, while resulting in an increase in the total flood volume due to the greater pore pressure required to disrupt the thicker cryosphere. An increase in the excess pore pressure required for outflow channel formation increases both the peak discharge and the total flood volume. [31] In order to highlight the importance of the dependence of the hydraulic parameters on the pore pressure, the simulation was repeated with the aquifer parameters held constant throughout the simulation at their initial values for the pressurized aquifer. A similar peak discharge of 8.3 106 m3 s1 was obtained at a time of 3.1 104 s. However, as a result of the maintenance of higher permeability throughout the aquifer despite the decreasing pore pressure, the discharge decreases much more slowly with time (Figure 5) and the minimum discharge is reached later in the simulation, at 7.7 107 s. Thus the dependence of the aquifer properties on the pore pressure provides for a more sharply peaked flood and a more rapid termination. [32] We now look below the surface at the aquifer response to the outflow event. In order to better visualize the patterns of flow within the aquifer, we consider a scaleddown model consisting of a 5 km radius chaos region in a 1 km thick cryosphere overlying a 1 km thick aquifer. The hydraulic head and permeability have been plotted in aquifer cross section at three different times (Figure 6). In the earliest stages of flow (t = 103 s), the discharge is dominated almost entirely by vertical flow from immediately beneath the chaos area. As the aquifer drains, the decrease in hydraulic head is accompanied by a decrease in permeability. After 104 s, there begins to be a significant component of lateral flow from the region peripheral to the chaos area. At this time the permeability has dropped by more than an order of magnitude in the upper portions of the aquifer beneath the chaos. At 105 s, the lateral flux from the 7 of 14 ANDREWS-HANNA AND PHILLIPS: MARTIAN OUTFLOW CHANNEL FLOODS E08001 E08001 Table 1. Effect of Cryosphere Thickness, Excess Pore Pressure, and Chaos Hydrofracture Width on the Discharges, Volumes, and Durations of Model Outflow Channel Floods ym,a km Ppore,b MPa wfiss, m 2 2 2 1 3 2 2 2i 2j 5 5 5 5 5 2 10 5 5 2.5 102 5 103 5 102 2.5 102 2.5 102 2.5 102 2.5 102 2.5 102 2.5 102 Qmax,c m3 s1 7.55 8.22 1.58 9.24 5.91 5.74 9.42 7.55 8.33 106 105 107 106 106 106 106 106 106 tmax, s 2.4 3.8 5.0 7.7 3.6 1.5 3.3 2.4 3.1 d 104 105 103 103 104 104 104 104 104 V(104 m3 s1),e km3 1.79 1.78 1.75 1.41 2.01 1.22 2.85 1.77 4.85 103 103 103 103 103 103 103 103 103 t(104 m3 s1),f s 3.6 3.6 3.5 2.4 4.4 2.8 4.9 3.5 7.7 107 107 107 107 107 107 107 107 107 V(105 m3 s1),g km3 1.02 1.02 9.95 8.92 1.08 6.14 1.81 1.01 3.16 103 103 102 102 103 102 103 103 103 t(105 m3 s1),h s 2.1 2.3 2.0 1.7 2.2 1.5 2.9 2.0 4.5 106 106 106 106 106 106 106 106 106 a Cryosphere thickness. Pore pressure in excess of lithostatic. Peak discharge. d Time of peak discharge. e Flood volume after minimum discharge of 104 m3 s1 is reached. f Time to reach minimum discharge of 104 m3 s1. g Flood volume after minimum discharge of 105 m3 s1 is reached. h Time to reach minimum discharge of 105 m3 s1. i Aquifer model with fracture apertures greater by a factor of 2. j Aquifer properties held constant at initial values throughout the simulation. b c chaos periphery is much greater than the vertical flux beneath the chaos region, though for large chaos areas the total discharge will still be dominated by the vertical flux of water from beneath the chaos region. The permeability at this time has decreased by more than 2 orders of magnitude in the upper portion of the aquifer beneath the chaos, such that the permeability is at a nearly constant value in the upper kilometer of the aquifer. At this time, the hydraulic head in the top 100 m of the aquifer has approached the hydrostatic value of 2 km relative to the base of the aquifer, suggesting that the chaos region presents little resistance to the flow. As a result, the discharge is determined primarily by diffusive flow through the aquifer, which is independent of the chaos region properties. In full-scale simulations, the pressure wave from the initiation of the flood (i.e., the maximum depth at which the decrease in hydraulic head as a result of the discharge to the surface is noticeable) reaches a depth of only about 6 km by the flood termination at approximately 107 s, as a result of the decreasing permeability with depth. Thus the discharge and volume of a single flood is unaffected by the aquifer properties at greater depths than this. Figure 6. (left) Hydraulic head in meters and (right) permeability in m2 within an aquifer during an outflow event from a small (5 km radius) chaos area at 103 s, 104 s, and 105 s after initiation of flow. The 1 km thick aquifer is overlain by a 1 km thick confining layer (not shown), breached by a chaos region extending from radii of 0 to 5 km. Superimposed over the hydraulic head are arrows representing the flow velocity vectors (normalized relative to the maximum velocity within each plot). 8 of 14 E08001 ANDREWS-HANNA AND PHILLIPS: MARTIAN OUTFLOW CHANNEL FLOODS [33] These modeled peak discharges fall significantly below the Ares Valles peak discharge estimate of 108 to 109 m3 s1 assuming bankfull flow, though we will argue below that this bankfull assumption results in gross overestimates of the discharge. Using equation (2), we calculate the flow depth during peak discharge for the baseline model flood to be only 54 m, significantly less than the channel depth of 1 km. The flood volumes also fall significantly short of the minimum volume required to carve Ares Valles, and in the next section we discuss the likelihood that the individual outflow channels actually formed through a large number of episodic floods. 4.2. Multiple Floods [34] Following the termination of the flood by freezing, much of the aquifer remains pressurized because of the low permeability of the deep portions of the aquifer and the large lateral length scales involved (Figure 6). After the flood termination, the pressurized fluid in these distal portions of the aquifer will continue to diffuse toward the drained portions, resulting in a repressurization of the aquifer beneath the chaos region. Eventually, the pore pressures beneath the chaos region will again reach superlithostatic levels, triggering a second flood. This cycle of flood termination, repressurization, and flood recurrence will repeat until the aquifer is sufficiently drained to be unable to generate additional flooding events. [35] We model the repressurization of the aquifer beneath the chaos region by continuing the simulated flow through the aquifer after the discharge through the chaos hydrofractures has been terminated. Figure 7 shows the evolution of the discharge to the surface, the integrated flood volume as a function of time, and the pore pressure at the base of the cryosphere beneath the chaos region over a series of three floods for the baseline model. As discussed above, the main period of peak discharge in the first flood lasts several days, and the total flood duration is on the order of a year (Figures 7a and 7b). The initial drop in pore pressure as the aquifer drains during the first flood is collapsed onto the y axis in Figure 7c. Following the termination of the first flood, the pore pressure in the aquifer just beneath the chaos region rises relatively rapidly over the first few tens of years, as the pressures from greater depths beneath the chaos region diffuse upward. This vertical diffusion is sufficient to eventually bring the pore pressure at the base of the cryosphere back up to lithostatic values in order to initiate a second flood after 1.4 109 s (44 years), and a similar pattern of aquifer depressurization and discharge to the surface ensues. Following the second flood, the deep aquifers beneath the chaos region have been sufficiently drained that vertical diffusion alone is not sufficient to trigger a third flood. Thus, after the initial period of rapid increase in pore pressure driven by vertical diffusion, the pore pressure continues to rise more slowly because of the lateral diffusion from the distal undrained portions of the aquifer, until a third flood is initiated at 9.7 109 s (310 years) after completion of the second. [36] The time between subsequent floods increases throughout the sequence, as more distal portions of the aquifer must be tapped to repressurize the aquifer beneath the chaos region. Erosion within the chaos region during subsequent floods will both reduce the thickness of the E08001 confining cryosphere and result in its structural weakening, thereby decreasing the threshold pore pressure necessary for flood reactivation and increasing the likelihood of subsequent flood outbursts. While this model has not explicitly included the erosion of the chaos region, the effect of such erosion would be to decrease the time between subsequent floods relative to our model results, particularly after a large number of floods have ensued. Since the model only represents the first few floods in the series, the effects of chaos erosion at this early stage in the flooding history are likely to be small. We have here simply assumed that the first flood occurs at some threshold pore pressure (5 MPa) above the lithostatic pressure, and subsequent floods are triggered when the pore pressure reaches the lithostatic pressure. The period of time between floods is also dependent on the assumed initial aquifer pore pressure. Greater initial pore pressures result in a shortened interflood period, particularly early in the simulations when the high pore pressures at great depth beneath the chaos region are able to repressurize the drained portions of the aquifer above. [37] For comparison, if we ignore the minimum discharge and allow a single flood to continue indefinitely, an arbitrarily large flood volume can be achieved for a flood of long enough duration. However, the majority of the flood occurs at exceedingly low discharge. For the baseline model, one year after initiation of the flood, the discharge has dropped by a factor of nearly 700 below the peak value, and a total flood volume of 1741 km3 has been released. After ten years, the discharge has dropped by a factor of 3200 below the peak value, with a total flood volume of 2880 km3. After 100 years, the discharge has dropped to only 700 m3 s1, a factor of more than 10,000 lower than the peak value, and a total flood volume of 6110 km3 has been released. A series of periodic floods would release nearly the same volume of water over a given period of time, but the flow would be concentrated in short bursts of high discharge flow, with the average discharge during periods of flooding inordinately greater than that of a single prolonged flood. [38] These results have assumed that an area much larger than the chaos region was initially pressurized to superlithostatic levels. Alternatively, it has been proposed that the outflow channels were driven by a steady source of recharge from precipitation and melting of ice deposits high on the Tharsis rise [Harrison and Grimm, 2004, 2005], or from a combination of the passive drainage of aquifers and a steady flux of water being ejected from deeply buried aquifers beneath Tharsis [Hanna and Phillips, 2006]. This same result of periodic outbursts as the chaos region is gradually repressurized would result from such a steady source of recharge, relaxing the requirement for the pressurization of the aquifer to superlithostatic levels over an area many times larger than the chaos region. The period of time between successive floods for the case of steady distant recharge will be dependent upon the recharge rate. The global hydrological models of Harrison and Grimm [2004, 2005] and Hanna and Phillips [2006] suggest average discharge rates over geologic timescales at the outflow channel sources to be on the order of several m3 s1. For comparison, the periodic floods modeled here have mean discharge rates averaged over the flood and interflood periods on the order of 100 to 1000 m3 s1. In order for these periodic floods to 9 of 14 E08001 ANDREWS-HANNA AND PHILLIPS: MARTIAN OUTFLOW CHANNEL FLOODS E08001 Figure 7. Evolution of the (a) discharge, (b) flood volume, and (c) subchaos pore pressure as a function of time for periodic floods from a 200 km radius chaos region representative of Iani Chaos at the source of Ares Valles. Note the different timescales used in each plot and discontinuities along the time axis in Figures 7a and 7b. be maintained by a global-scale aquifer recharge rate of 1 m3 s1, the individual flood volume of 1000 km3 requires an interflood period of order 104 years. If the global-scale hydrology succeeded in pressurizing a regional aquifer to lithostatic pressures, then the floods would initially recur over short timescales (102 years) as suggested in this work, with the interflood periods gradually lengthening as the regional aquifers drained, until an interflood period capable of being sustained by the globalscale flow was achieved. The total flood volume in either case will depend on the number of flood episodes, which in turn depends on either the extent of the pressurized aquifer or the duration and rate of distant recharge. In order to achieve the estimated minimum flood volume from Iani Chaos of 3 104 km3, the flood volumes given in Table 1 would require a minimum of between 6 and 49 individual floods. If the sediment loads carried by the floods were less than the maximum value of 0.4 assumed, the number of floods required would increase accordingly. 4.3. Erosive History and Geomorphic Implications [39] As stated earlier, a common assumption in many studies of the outflow channels is that they were formed in single floods with peak discharges occurring under bankfull conditions in the observed channel. Our results suggest that both of these assumptions are gross oversimplifications for outflow channels originating within chaos regions. The discharges in these floods would have peaked early in the flood, followed by long periods of lower discharge until the floods terminated as a result of freezing within the chaos region. Similarly, the rate of channel erosion should peak early in the floods, but be followed by extended periods of decreasing erosion in the later stages of the floods. As a result, the channels during the peak discharge of the first flood will only be a fraction of their final size. Furthermore, the observed channels were likely carved by a large number of floods, with each flood only responsible for a fraction of the erosion, and with successive floods decreasing in magnitude as the aquifer depressurizes and the threshold for outflow reactivation decreases because of erosion in the chaos region. [40] There is currently no generally accepted and universally applicable relationship between channel flow dynamics and erosion within a bedrock channel. Most models relate the erosion rate, e_ , to either the stream shear stress on 10 of 14 E08001 ANDREWS-HANNA AND PHILLIPS: MARTIAN OUTFLOW CHANNEL FLOODS the bed, t, or the stream power, w [Sklar and Dietrich, 1998]: e_ ¼ Kt t ¼ Kt rw gdS ð9Þ e_ ¼ Kw w ¼ Kw tu ð10Þ where S is the hydraulic slope, u is the flow velocity, d is the flow depth, and Kt and Kw are dimensional parameters that are poorly constrained and highly dependant upon the mechanism of erosion and the rock type. Whipple et al. [2000] argued that the erosion rate is best represented as e_ ¼ Kt t a ð11Þ where the exponent a is dependent upon the erosive process. Considering the physical processes behind the key erosive mechanisms, they estimated exponent values of 3/2, 5/2, and up to 7/2 for plucking, abrasion by suspended load, and cavitation, respectively. The cavitation model was poorly constrained, and they noted a lack of direct observational evidence for cavitational erosion within the bedrock channels of their study. Furthermore, Wilson et al. [2004] found that the supercritical flow required for cavitation was not likely to have occurred during the outflow channel floods. It has been argued that erosion by plucking was important for both the Channeled Scablands of eastern Washington State and the outflow channels [Baker, 1979; Baker and Milton, 1974], suggesting that a shear stress exponent of 3/2 is most representative of the erosion in the outflow channels. However, the longitudinal striations and streamlined islands observed in some channels [Baker and Milton, 1974] are likely the result of scouring by suspended load, suggesting a shear stress exponent of 5/2. [41] The current understanding of erosion in terrestrial bedrock channels, in particular the value of the proportionality constants Kt and Kw, is insufficient to be able to directly calculate the erosion rate expected to result from the modeled outflow channel hydrographs. However, the relationships in equations (9) through (11) allow us to gain insight into the variation of the relative erosion rate during an outflow flood. We calculate the normalized erosion rate as a function of time for the baseline outflow flood model, considering the shear stress erosion models with stress exponents of 1, 3/2, 5/2, and 7/2. The flow velocity and depth as a function of time are calculated from the discharge curve using equation (2) and the observed geometry of Ares Valles. The normalized integrated eroded depths are plotted in Figure 8 alongside the normalized flow depth for our baseline flood model with a minimum discharge of 104 m3 s1. As expected, the channels are only partially eroded at the time of peak discharge. For the median shear stress exponents of 3/2 and 5/2, the channel has only reached only 5% to 22% of its final depth at the time of peak discharge. By the time the discharge has dropped by a factor of 10 below its peak value, the channel will have reached 26% to 78% of its final depth. Stated another way, if one were to make the simplistic and unwarranted assumption that the channel was carved in a single flood and was exactly bank full at the time of peak discharge, E08001 these results suggest that the flow depth and channel depth at this time would have been between 5% and 22% of the observed final channel depth. Note that for this simple scenario of bankfull flow during peak discharge, the high water marks would be coincident with the channel top, but the channel base at the time of this peak discharge would have been situated well above its final value. [42] The above treatment neglects a number of complicating factors. As demonstrated in section 4.2, the outflow channels were likely carved in multiple events, with diminishing flood discharges and volumes for successive events. Each event would carve the channel deeper, and thus each successive flood would fall further short of the bankfull condition. On the other hand, the ability of a single flood to transport sediment of a given size is proportional to the square of the flow velocity [Whipple et al., 2000]. Thus, as the discharge decreases by approximately 2 orders of magnitude from its peak value to the waning stages of the flood, the larger sized fractions of the suspended and bed load will settle out of the flow and could form an armoring deposit over the channel bed. This effect could diminish the erosive effectiveness of the flood in the later stages, and result in a focusing of the erosion in the early stages. [43] This analysis is not meant to quantitatively reproduce the erosion during an outflow channel event, but rather to illuminate the general pattern of the erosive history of the channels. The results suggest that the assumption of bankfull flow within the final observed channel is a gross overestimate, both because of the continued erosion of the channel after attainment of peak discharges and the likelihood of multiple floods. It also suggests that the use of high water marks in the reconstruction of the flow is unreliable, since the correlation of a particular high water mark with a known channel base level is not generally possible. 4.4. Channeled Scabland Analog [44] While the conclusion that the individual outflow channels were likely carved in a large number of discrete events conflicts with the classical paradigm of their formation through one or several floods, the concept of a series of repeating catastrophic floods has precedent in the terrestrial literature. The Channeled Scablands of eastern Washington State are commonly held as the best terrestrial analog to the Martian outflow channels [Baker and Milton, 1974], and we here extend that analogy to the number and nature of the floods. [45] Early interpretations of the Channeled Scablands assumed that they were carved by the release of one, or perhaps several, catastrophic floods of water [Bretz, 1923; Bretz et al., 1956]. However, later evidence suggested that they had in fact been carved by a large number of floods, perhaps as many as 89, in a periodic succession [Wait, 1980, 1984, 1985]. The evidence for this series of many floods came not from erosional features, but rather from depositional features, in which the deposits from individual floods are preserved in backwaters and separated by varved lake sediments (Figure 9). This record preserves both the number and timing of the floods, suggesting that individual floods were separated by periods of several to tens of years. The periodic nature of the floods is a result of the mechanism for the flood generation. The Channeled Scabland floods are thought to have formed because of the catastrophic drainage 11 of 14 E08001 ANDREWS-HANNA AND PHILLIPS: MARTIAN OUTFLOW CHANNEL FLOODS E08001 combination of steady recharge with a threshold for release is predicted to result in an episodic flooding history. 5. Discussion and Conclusions Figure 8. Plot versus time of the normalized flow depth and normalized erosional depth for the baseline flood model during the early stages of the flood for different dependences of the erosion rate on the shear stress (t). of glacial Lake Missoula, formed when a lobe of the Cordilleran ice sheet dammed a major drainage network [Alt, 2001]. The river water ponded behind the glacier until it reached a sufficient depth to float the ice sheet, and then flowed out from underneath in a jökulhaup-style flood. The first flooding event was followed by a period of several tens of years as the river water again pooled behind the glacier, until it reached a sufficient depth to again float the glacier and initiate a second flood. This process would continue as long as the glacier dammed the river outlet and the fluvial system upstream of the dam persisted. [46] The analogy between the repeating floods in the Channeled Scablands and the outflow channel floods is twofold. First, the Channeled Scablands demonstrate that it can be difficult to distinguish between a single flood and a large number of floods based on the resulting erosional landforms alone. The geomorphic signatures of the two can be indistinguishable. This suggests that evidence of the number and timing of the Martian outflow channel floods may be found in the associated sedimentary deposits rather than in the erosional record of the channels. Second, there is a strong analogy between the nature of the processes responsible for the recurring floods on Earth and Mars. For both cases, there is a steady buildup of water until a threshold is reached and flooding ensues, followed by a period of recharge until the threshold is again reached and the process repeats. For the terrestrial case, the threshold is the attainment of a lake level sufficient to float the glacial dam, and the recharge is a result of the continued drainage of the upstream areas and flow through the river to the dammed glacial lake. For the Martian case, the threshold is the attainment of superlithostatic pore pressures in the aquifer beneath the confining cryosphere, and the recharge is the steady flow through the aquifer from the undrained and still pressurized portions of the aquifer to the drained portions at the source of the floods. In both cases, this [47] Detailed modeling of the process of outflow channel initiation and the aquifer response to an outflow event has led to predicted maximum discharges and total flow volumes that are consistent with the observed channel geomorphology. We find that the discharge from a chaos source is dominated by vertical flow from directly beneath the chaos. The predicted discharges decrease rapidly after the peak discharge, consistent with the interpretations of the outflow channel floods as catastrophic and short-lived events. During a single flood, continued erosion after the attainment of peak discharges would have continued to increase the channel depth by a factor of 5 to 20. After termination of the flood, the high pore pressures diffuse from the undrained portions of the aquifer back toward the chaos region, resulting in a repressurization that triggers additional episodes of flooding. Individual floods persist for months to years, and are separated by minimum interludes of 10s to 100s of years. Thus the outflow channels were likely carved by large numbers of floods over long periods of time, and the channels in their final form were not likely to have ever experienced bankfull flow. For Iani Chaos at the source of Ares Valles, the model predicts a minimum of 6 to 49 floods with peak discharges on the order of 106 to 107 m3 s1. This scenario is consistent with the observation of small inner channels within some outflow channels [Williams et al., 2000; Williams and Malin, 2004], which is suggestive of multiple flooding events. Nevertheless, we suggest that the observed erosional record may belie the true number of floods, as in the Channeled Scablands. [48] The outflow channels pose a curious conundrum: the geomorphic evidence suggests they were carved by catastrophic floods from groundwater sources, and yet groundwater flow is an inherently gradual and diffusive process. While transient high discharges can be produced from groundwater flow [Carr, 1979], they are followed by long periods of much lower discharges that decrease with time as Figure 9. Sediment layers (rhythmites) deposited in a backwater environment during multiple floods in the Channeled Scablands of eastern Washington State (photograph by J. Andrews-Hanna). 12 of 14 E08001 ANDREWS-HANNA AND PHILLIPS: MARTIAN OUTFLOW CHANNEL FLOODS a power law. The periodic series of floods proposed here would deliver the same volume of water to the surface as a single sustained long-duration flood, but in a series of highdischarge bursts punctuated by long periods with no flow, increasing the net catastrophic nature of the floods. [49] The volumes and durations of the floods forming the outflow channels have significant implications for the volatile evolution of Mars. It has been suggested that the outflow channels played a key role in delivering volatiles to the surface of Mars during the Hesperian, possibly filling a northern ocean or driving climate change [Gulick et al., 1997]. These results suggest that individual outflow channels did not form all at once, but rather in a series of several to hundreds of individual floods, separated by periods of tens to hundreds of years. Such a flooding history would make the generation of a northern ocean or a significant climate change more difficult, as suggested by Williams et al. [2000]. Under the present climatic regime, the comparatively small volumes of the individual floods may be more likely to freeze, sublimate, and condense onto the poles, rather than pond to form an ocean [Kreslavsky and Head, 2002]. The ultimate fate of the outflow channel effluents is essential to our understanding of the volatile and climate history of Mars during the Hesperian, but the channel geomorphology alone does not sufficiently illuminate the nature and history of the floods to reveal this fate. This work suggests that understanding the hydrology of outflow channel genesis is crucial to understanding their impact on the Martian environment. [50] Acknowledgments. We would like to thank Keith Harrison and an anonymous reviewer for comments that helped to improve and clarify the manuscript. This work was supported at Washington University by grants NNG05GQ81G and NNX06AB92G from NASA. The authors acknowledge the use of Mars Orbiter Camera images processed by Malin Space Science Systems that are available at http://www.msss.com/moc_ gallery/. References Alt, D. (2001), Glacial Lake Missoula and Its Humongous Floods, 199 pp., Mountain Press, Missoula, Mont. Baker, V. R. (1979), Erosional processes in channelized water flows on Mars, J. Geophys. Res., 84, 7985 – 7993. Baker, V. R. (1982), The Channels of Mars, 198 pp., Univ. of Tex. Press, Austin. Baker, V. R., and D. J. Milton (1974), Erosion by catastrophic floods on Mars and Earth, Icarus, 33, 27 – 41. Bargery, A. S., L. Wilson, and K. Mitchell (2005), Modeling catastrophic floods on the surface of Mars, Lunar Planet. Sci. [CD-ROM], XXXVI, Abstract 1961. Bretz, J. H. (1923), The channeled scabland of the Columbia plateau, Geology, 32, 139 – 149. Bretz, J. H., H. T. U. Smith, and G. E. Neff (1956), Channeled scabland of Washington: New data and interpretations, Geol. Soc. Am. Bull., 67, 957 – 1049. Carr, M. H. (1979), Formation of Martian flood features by release of water from confined aquifers, J. Geophys. Res., 84, 2995 – 3007. Carr, M. H. (1987), Volumes of channels, canyons, and chaos in the circumChryse region of Mars (abstract), Lunar Planet. Sci., XVIII, 155 – 156. Carr, M. H. (1996a), Channels and valleys on Mars: Cold climate features formed as a result of a thickening cryosphere, Planet. Space Sci., 44, 1411 – 1423. Carr, M. H. (1996b), Water on Mars, 229 pp., Oxford Univ. Press, New York. Clow, G. D. (1994), Minimum discharge rates required for sustained water flow on the Martian surface (abstract), Lunar Planet. Sci., XXV, 275 – 276. Domenico, P. A., and F. W. Schwartz (1990), Physical and Chemical Hydrogeology, 824 pp., John Wiley, New York. French, R. H. (1985), Open-Channel Hydraulics, 739 pp., McGraw-Hill, New York. E08001 Gudmundsson, A., S. Berg, K. Lyslo, and E. Skurtveit (2001), Fracture networks and fluid transport in active fault zones, J. Struct. Geol., 23, 343 – 353. Gulick, V. C., D. Tyler, C. P. McKay, and R. M. Haberle (1997), Episodic ocean-induced CO2 greenhouse on Mars: Implications for fluvial valley formation, Icarus, 130, 68 – 86. Hanna, J. C., and R. J. Phillips (2005), Hydrological modeling of the Martian crust with application to the pressurization of aquifers, J. Geophys. Res., 110, E01004, doi:10.1029/2004JE002330. Hanna, J. C., and R. J. Phillips (2006), Tharsis-driven hydrology and the Martian outflow channels, Lunar Planet. Sci. [CD-ROM], XXXVII, Abstract 2373. Harrison, K. P., and R. E. Grimm (2004), Tharsis recharge: A source of groundwater for Martian outflow channels, Geophys. Res. Lett., 31, L14703, doi:10.1029/2004GL020502. Harrison, K. P., and R. E. Grimm (2005), Tharsis recharge and the Martian outflow channels: Observations and recent modeling, Lunar Planet. Sci. [CD-ROM], XXXVI, Abstract 1211. Hart, S. R. (1993), Equilibration during mantle melting: A fractal tree model, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 90, 11,914 – 11,918. Hartmann, W. K., and G. Neukum (2001), Cratering chronology and the evolution of Mars, Space Sci. Rev., 96, 165 – 194. Hauck, S. A., II, and R. J. Phillips (2002), Thermal and crustal evolution of Mars, J. Geophys. Res., 107(E7), 5052, doi:10.1029/2001JE001801. Head, J. W., L. Wilson, and K. L. Mitchell (2003), Generation of recent massive water floods at Cerberus Fossae, Mars by dike emplacement, cryospheric cracking, and confined aquifer groundwater release, Geophys. Res. Lett., 30(11), 1577, doi:10.1029/2003GL017135. Jacob, C. E., and S. W. Lohman (1952), Nonsteady flow to a well of constant drawdown in an extensive aquifer, Eos Trans. AGU, 33, 559. Kleinhans, M. G. (2005), Flow discharge and sediment transport models for estimating a minimum timescale of hydrological activity and channel and delta formation on Mars, J. Geophys. Res., 110, E12003, doi:10.1029/ 2005JE002521. Knighton, D. (1998), Fluvial Forms and Processes, Oxford Univ. Press, New York. Komar, P. D. (1980), Modes of sediment transport in channelized water flows with ramifications to the erosion of the Martian outflow channels, Icarus, 42, 317 – 329. Komatsu, G., and V. R. Baker (1997), Paleohydrology and flood geomorphology of Ares Valles, J. Geophys. Res., 102, 4151 – 4160. Kreslavsky, M. A., and J. W. Head (2002), Fate of outflow channel effluents in the northern lowlands of Mars: The Vastitas Borealis Formation as a sublimation residue from frozen ponded bodies of water, J. Geophys. Res., 107(E12), 5121, doi:10.1029/2001JE001831. Leask, H. J., L. Wilson, and K. L. Mitchell (2004), The formation of Aromatum Chaos and the water discharge rate at Ravi Vallis, Lunar Planet. Sci. [CD-ROM], XXXV, Abstract 1544. Leask, H., L. Wilson, and K. Mitchell (2007), Formation of Mangala Valles outflow channel, Mars: Morphological development, and water discharge and duration estimates, J. Geophys. Res., doi:10.1029/2006JE002851, in press. Manga, M. (2004), Martian floods at Cerberus Fossae can be produced by groundwater discharge, Geophys. Res. Lett., 31, L02702, doi:10.1029/ 2003GL018958. Mitchell, K. L., F. Leesch, and L. Wilson (2005), Uncertainties in water discharge rages at the Athabasca Valles paleochannel system, Mars, Lunar Planet. Sci. [CD-ROM], XXXVI, Abstract 1930. Nelson, D. M., and R. Greeley (1999), Geology of the Xanthe Terra outflow channels and the Mars Pathfinder landing site, J. Geophys. Res., 104, 8653 – 8669. Peck, D. L., and T. Minakami (1968), The formation of columnar joints in the upper part of Kilauean lava lakes, Hawaii, Geol. Soc. Am. Bull., 79, 1151 – 1166. Robinson, M. S., and K. L. Tanaka (1990), Magnitude of a catastrophic flood event at Kasei Valles, Mars, Geology, 18, 902 – 905. Rotto, S. L., and K. L. Tanaka (1992), Chryse Planitia region, Mars: Channeling history, flood volume estimates, and scenarios for bodies of water in the northern plains, in Workshop on the Martian Surface and Atmosphere Through Time, edited by R. M. Haberle et al., Tech. Rep. 92-02, pp. 111 – 112, Lunar and Planet. Inst., Houston, Tex. Skinner, J. A., and K. L. Tanaka (2000), Southern Chryse outflow channels, Mars: Origin of reversed channel gradients and chaotic depressions, Lunar Planet. Sci. [CD-ROM], XXXI, Abstract 2076. Sklar, L., and W. E. Dietrich (1998), River longitudinal profiles and bedrock incision models: Stream power and the influence of sediment supply, in Rivers Over Rock: Fluvial Processes in Bedrock Channels, Geophys. Monogr. Ser., vol. 107, edited by K. J. Tinker and E. E. Wohl, pp. 237 – 260, AGU, Washington, D. C. 13 of 14 E08001 ANDREWS-HANNA AND PHILLIPS: MARTIAN OUTFLOW CHANNEL FLOODS Smith, D. E., et al. (2001), Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA): Experiment summary after the first year of global mapping of Mars, J. Geophys. Res., 106, 23,689 – 23,722. Tritton, D. J. (1988), Physical Fluid Dynamics, 519 pp., Clarendon, Oxford, U. K. Wait, R. B. (1980), About forty last-glacial Lake Missoula jökulhaups through southern Washington, Geology, 88, 653 – 679. Wait, R. B. (1984), Periodic jökulhaups from varved sediment in northern Idaho and Washington, Quat. Res., 22, 46 – 58. Wait, R. B. (1985), Case for periodic, colossal jökulhaups from Pleistocene glacial Lake Missoula, Geol. Soc. Am. Bull., 96, 1271 – 1286. Whipple, K. X., G. S. Hancock, and R. S. Anderson (2000), River incision into bedrock: Mechanics and relative efficacy of plucking, abrasion, and cavitation, Geol. Soc. Am. Bull., 112, 490 – 503. Williams, R. M. E., and M. C. Malin (2004), Evidence for late stage fluvial activity in Kasei Valles, Mars, J. Geophys. Res., 109, E06001, doi:10.1029/2003JE002178. E08001 Williams, R. M., and R. J. Phillips (1999), Morphometry of the circumChryse outflow channels: Preliminary results and implications, paper presented at Fifth International Conference on Mars, Calif. Inst. of Technol., Pasadena, Calif. Williams, R. M., R. J. Phillips, and M. C. Malin (2000), Flow rates and duration within Kasei Valles, Mars: Implications for the formation of a Martian ocean, Geophys. Res. Lett., 27, 1073 – 1076. Wilson, L., G. J. Ghatan, J. W. Head III, and K. L. Mitchell (2004), Mars outflow channels: A reappraisal of the estimation of water flow velocities from water depths, regional slopes, and channel floor properties, J. Geophys. Res., 109, E09003, doi:10.1029/2004JE002281. J. C. Andrews-Hanna, Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA. (jhanna@mit.edu) R. J. Phillips, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Washington University, St. Louis, MO 63130, USA. 14 of 14