National Amyloidosis Centre News

advertisement

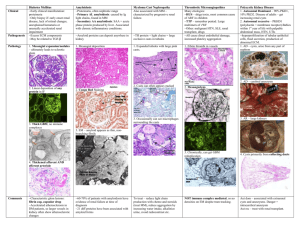

Professor Sir Mark Pepys FRS FMedSci, Director of the Wolfson Drug Discovery Unit, with the screen in the background showing the appearance of amyloid deposits viewed in a biopsy NAC leads the way to improved amyloidosis diagnosis in the UK Early and correct diagnosis of amyloidosis is essential so that patients can benefit from appropriate and timely treatment. As with any rare disease, diagnosis first depends on physicians thinking of it, and then requires the use of correct diagnostic techniques. Doctors, scientists or technicians, who are expert at examining biopsy slides under the microscope, are responsible for making the laboratory diagnosis of amyloidosis. In order to detect and identify amyloid, biopsy slides must be properly prepared, stained and examined. Each of these three stages requires precise techniques, correct equipment and professional expertise, or amyloid deposits may be missed (false negative result) or incorrectly diagnosed when there is actually no amyloid present (false positive result). The box on the next page lists the technical steps involved in histological diagnosis of amyloid. We see about 3,500 patients at the National Amyloidosis Centre every year, including about 50% of all UK patients with systemic amyloidosis. Our expert laboratory staff, led by Janet Gilbertson, also review hundreds of biopsies annually in addition to our own patient throughput. Professor Sir Mark Pepys began seeing patients with amyloidosis at the Hammersmith Hospital in 1977. In 1986 Professor Philip Hawkins joined his unit and together they soon provided the de facto national referral service for amyloidosis in the UK. They subsequently established the UK National Amyloidosis Centre at the Royal Free Hospital in 1999. Over the years the expanding NAC team has been acutely aware of the worryingly high frequency of both false positive and false negative histology reports from elsewhere, based on incorrect use or interpretation of Congo red staining. A recent audit by Janet Gilbertson found that both false positives and false negatives in recent years, amongst biopsy specimens sent to her for review, have run at about 8% in both directions. She was also surprised to discover that about 20% of accredited histopathology laboratories do not even possess polarising filters on their microscopes. Without these they cannot possibly diagnose amyloid, as slides must be viewed through such filters in order to make the diagnosis. National Amyloidosis Centre News ISSUE 3: March 2014 IN THIS ISSUE Improving amyloid diagnosis in the UK 1 Patient story: Dr David Webster 3 Focus on senile Systemic amyloidosis 4 New equipment purchased by the UCL Amyloidosis Research Fund 7 Fundraising news 8 Upcoming fundraising challenge 10 Donations 12 National Amyloidosis Centre, UCL Division of Medicine, Royal Free Campus, Rowland Hill Street, London NW3 2PF, UK www.ucl.ac.uk/amyloidosis National Amyloidosis Centre News 2 Issue 3: March 2014 In mid-2013 Professor Sir Mark Pepys set out to address the problem and to help patients by improving amyloidosis diagnosis throughout the country. To pursue this goal, he initiated collaboration between the NAC laboratory team and the United Kingdom National External Quality Assessment Service (UK NEQAS). UK NEQAS comprises a network of quality assessment and educational schemes and most histopathology laboratories that wish to be accredited are signed up and participate in these schemes. The objective of UK NEQAS is to help ensure that the results of investigations are reliable and comparable wherever they are produced. In 2014, Janet Gilbertson and Dr Glenys Tennent will be actively engaged in the amyloid modules of the UK NEQAS scheme. Dr Tennent is the Senior Lecturer in the Wolfson Drug Discovery Unit and a world expert in histological diagnosis and characterisation of amyloid with over 30 years of experience. • Written an article highlighting the reasons behind the Centre’s involvement in the scheme, and detailing best practice for amyloid diagnosis, for inclusion in the next UK NEQAS newsletter which is distributed to over 400 cell pathology laboratories nationwide. Over the course of 2014, Dr Tennent will direct and advise assessors and participants in several UK NEQAS training activities. She will advise course leaders during training courses, direct and advise assessors as they review thousands of slides. She will also give a lecture about amyloid diagnosis at the UK NEQAS national meeting in autumn 2014. In Professor Sir Mark Pepys’s words, “making the diagnosis months or years earlier in even a few of the many amyloidosis patients whose diagnosis is long delayed by poor histopathology every year, will definitely save lives and reduce suffering and costs”. We hope to eventually ensure that every diagnostic histopathology department in the UK knows how to stain with Congo red so that the dye is as specific as possible for amyloid deposits. Crucially, they also need to all be equipped with polarising filters and to be sufficient experienced to recognise and identify amyloid. We are optimistic that the planned activities will help to bring us closer to this goal, thereby improving standards of amyloid diagnosis and benefitting many patients. To date, they have: • Updated the UK NEQAS Amyloid Staining Assessment Criteria. • Provided standard amyloid biopsy material for distribution to all UK diagnostic laboratories participating in the scheme, for assessment of their amyloid staining techniques. Technical steps involved in the laboratory diagnosis of amyloid 1. Biopsy or resected tissue specimen is brought to the lab. 2. The tissue is fixed and embedded in paraffin to preserve it. 3. Sections are cut from the fixed tissue – section thickness must be correct. 4. The sections are placed on a slide and stained with Congo red dye – this must be done very precisely to ensure reliable results. 5. The stained sections are mounted in a microscope and examined under strong cross polarised light – this requires special polarising filters in the microscope. Bright green appearance of amyloid deposits when they have been prepared, stained and viewed correctly National Amyloidosis Centre News Issue 3: March 2014 3 Patient story: Dr David Webster The story starts with an abnormal routine ECG I had been a keen sportsman since my early school days, focusing on rugby at university and medical school, and then starting to play regularly again in my early thirties at quite a high level and then in more social teams until I was forty-eight. I regarded myself as physically fit during my fifties although I developed arthritis in my right hip that was surgically replaced, allowing me to continue an active lifestyle with regular swimming, gym sessions and winter skiing. By my mid-sixties the other hip had deteriorated and I was heading for more surgery in 2007 when my ‘amyloid’ story really started. As a hospital consultant physician, I immediately realised the potential implications when a routine ECG revealed a conduction defect (left bundle branch block) in my heart during a pre-operative assessment for hip replacement. This was a big surprise as I considered myself very fit for my age. I had noticed some recent slight shortness of breath on reaching the top of the four flights of stairs to my office over the previous few months, but had put this down to advancing age. My surgery was postponed while a series of investigations were done over the next six months, undoubtedly speeded up by initially seeing a cardiologist privately and having some expensive tests done quickly. My cardiologist, a consultant colleague at the Royal Free Hospital where I worked as a Professor of Immunology, initially thought the cause was probably ‘heart strain’ due to high blood pressure, but this was excluded after being fitted with a 24-hour monitoring system. I remember him mentioning very rare causes of heart conduction defects, one of which was amyloid, but he thought this extremely unlikely as the rest of my body seemed in good working order. However an echocardiogram was suggestive of amyloidosis, as it showed a thickened heart wall with a suspicion of muscle infiltration. A cardiac MRI scan was then arranged at the Royal Brompton Hospital which I gather was the only place in London at that time with a suitable machine, and where research was being done to find out if cardiac amyloid could be diagnosed using this non-invasive procedure. Confirming the diagnosis Meanwhile it was considered safe to proceed with my hip replacement. However, the day before surgery I had a phone call from my surprised cardiologist who told me that the MRI was typical of amyloidosis. Although encouraged to proceed with the surgery I reckoned my anaesthetist would ‘abandon ship’ when I told him I had amyloid cardiomyopathy, so I urgently contacted Professor Hawkins in the NAC for his opinion and was advised to postpone surgery again until further investigations were completed. An SAP scan at the NAC showed I had no amyloid infiltrating other organs so the diagnosis was still in doubt and could only be confirmed by a cardiac biopsy. My doctors were a little reticent in advising this procedure because there was no cure if the diagnosis was confirmed. However, I prefer certainty to uncertainty so I went to the Heart Centre at Harefield Hospital where Dr Banner and his impressive team took small pieces of muscle from the left side of my heart with a tiny ‘grab’ on the end of a wire threaded through an artery in my leg, all under local anaesthetic. Special tests at the NAC on the biopsies confirmed TTR amyloid, but tests on my DNA found none of the rare inherited gene defects known to cause this condition. This left me with the official diagnosis of ‘senile systemic amyloidosis’, a label that does not instil much confidence in the future! Experimental treatment and then ‘heart block’ As a specialist familiar with medical research on novel diseases, I quickly grasped that I was one of the few patients in the UK diagnosed while in relatively good physical health, and that any attempts at treatment would be experimental, with the side effects possibly being worse than the disease. Furthermore nothing much was known about the natural progression of ‘senile’ TTR amyloid, making it difficult to assess the impact of any new treatments. This is one of those situations where it is best not to be a medically qualified patient as ‘ignorance can be bliss’! However, having National Amyloidosis Centre News 4 Issue 3: March 2014 spent a career persuading patients to take part in various drug trials, I saw the humorous side of having to step forward myself! I started taking diflunisal, a drug originally developed for arthritis but more recently found to stabilise TTR and possibly prevent it from entering the heart, with the immediate upside being an improvement in my left hip which was still awaiting surgery. Nothing much changed over the next year but then suddenly I began to get pain in my abdomen after walking and my ankles started swelling. After an urgent admission to hospital complete ‘heart block’ was diagnosed, my pulse having fallen to only 30 beats per minute. A pacemaker/defibrillator was inserted under the skin on my chest and I was immediately back to ‘normal’. The pacemaker also checked my heart activity and rhythm, transmitting this information regularly to my cardiologists through a monitor attached to my home telephone. Having got over the initial sensation of being ‘controlled from outer space’ I felt more secure and less likely to die suddenly from a cardiac event than others of my age. This episode finally convinced my wife that there really was something seriously wrong with my heart! I was now in a lot of pain from my hip so at last this was successfully replaced in early 2011. About 18 months later the cardiac monitor showed episodic atrial fibrillation and I was advised to start on anti-coagulants; this meant I had to stop the diflunisal which anyway seemed to have had little or no impact on my disease. I managed to persuade my doctors to prescribe one of the new anticoagulants, dabigatran, which suited my busy life-style better than the traditional warfarin which needs regular monitoring of dose. More information needed for doctors and public At my age you start to accumulate old friends with cardiac pacemakers and abnormal heart rhythms, and I often wonder whether their doctors have done the appropriate tests for ‘senile’ TTR amyloid; I suspect not but am too polite to enquire! My experience of major and minor (a hernia repair) surgery over recent years is that anaesthetists ‘run for cover’ when you tell them you have cardiac amyloid. Although my hip surgery was uneventful they did take fright and called in a specialist cardiac anaesthetist, and kept me closely monitored in a high dependency unit for 24 hours afterwards. This was probably unnecessary and research is needed to assess the surgical risks in my type of amyloid so that anaesthetists can be more informed and confident. Six years from diagnosis I am now close to being seventy four, and six years from the initial diagnosis of my cardiac amyloid. Despite some deterioration in heart function requiring a pacemaker, anti-coagulant pills, and a couple of other daily tablets to stabilise and reduce the strain on my heart, my exercise tolerance has not significantly changed and I have been able to continue doing medical research. The only thing I notice is a transient feeling of exhaustion and muscle fatigue when I suddenly move from a sitting position to walk or go up two flights of stairs, as if my heart is slow to get into gear. Once I am moving I can walk or cycle for miles at a steady pace. The specialists at the NAC tell me that clinical trials on some exciting new drugs for TTR amyloid will start soon, so perhaps I will be climbing Everest at the age of eighty after all! Focus on senile systemic amyloidosis In senile systemic amyloidosis (SSA) a normal blood protein called transthyretin (TTR) is the amyloid precursor protein that clumps together and forms ATTR amyloid deposits, mainly in the heart and often also in the part of the wrists called the carpal tunnel, causing wrist pain and tingling called “carpal tunnel syndrome”. Senile systemic amyloidosis is not an inherited condition (does not run in families). Symptoms usually start over the age of 65 and the disease usually progresses slowly. It is far more common in men than in women and may affect people from any ethnic background. Other types of ATTR amyloidosis are inherited, affecting people with genetic alterations (mutations) in the TTR gene. People with these mutations have structurally abnormal, amyloid-forming (amyloidogenic), “variant” TTR in their blood. People with senile systemic amyloidosis have only the normal, “wild-type” TTR in their blood, and do not have any abnormal “variant” TTR. National Amyloidosis Centre News Issue 3: March 2014 5 More common than we thought Nobody knows how common senile systemic amyloidosis really is. Small amyloid deposits consisting of “wild-type” ATTR amyloid are very common, found in the hearts and blood vessels of 1 in 4 people over the age of 80 in autopsy studies. Until recently it was believed that this type of amyloid deposit was hardly ever extensive enough to cause symptomatic heart disease. But in recent years, new cardiac imaging techniques (DPD scans and cardiac MRI) have shown that, in fact, “wild type” ATTR deposits causing senile systemic amyloidosis may be a far more common cause of heart disease than anyone thought. The graph here shows the diagnoses of new amyloidosis patients seen at the NAC each year since 2000. The overall number of patients seen at the NAC has more than doubled in this time, with AL amyloidosis remaining the most common diagnosis, and accounting for about half of all patients diagnosed. Relative proportions of patients with most types of amyloidosis have remained fairly steady. But the rate of senile systemic amyloidosis diagnosis has shot up dramatically, as shown by the purple coloured area on the graph. A graph showing diagnoses of new amyloidosis patients seen at the NAC each year since 2000 In the year 2000, just one patient seen at the NAC had senile systemic amyloidosis, and in 2012, 62 patients were diagnosed with this condition. Nobody knows whether this just represents the tip of the iceberg. The coming years could see a continuing increase in the frequency with which senile systemic amyloidosis is diagnosed. Even though there is no specific treatment for senile systemic amyloidosis at present, patients benefit greatly from having the correct diagnosis, as their doctors can then avoid prescribing unhelpful drug therapies that are used in “ordinary” heart failure. There are also several specific treatments for senile systemic amyloidosis under development at present (discussed below). It is hoped that patients will soon be able to benefit from these. What causes amyloidosis? senile systemic The cause of senile systemic amyloidosis is unknown – we do not know why “wild-type” TTR, which is a normal blood protein, forms amyloid deposits in some people and not in others although advancing age is undoubtedly a risk factor. Symptoms ATTR amyloid deposits in the heart muscle may cause no symptoms at all if they are small. But when amyloid deposits in the heart are large, they can lead to stiffening of the heart muscle, called “restrictive cardiomyopathy”. When the heart muscle is stiff, the heart is unable to pump the blood around the body as efficiently as usual. Symptoms of heart failure may then appear, including: • breathlessness, sometimes just after mild exertion • abnormal heart rhythms – most commonly atrial • • • • • • • fibrillation and atrial flutter palpitations swelling of the legs weight loss nausea dizziness and collapse (syncope) disrupted sleep fatigue Breathlessness may be worse during exercise or when lying flat at night. Patients may feel more comfortable propped up with several pillows. At the time of diagnosis, heart failure symptoms are usually less severe in patients with senile systemic National Amyloidosis Centre News 6 Issue 3: March 2014 amyloidosis than in those with AL amyloid deposits in the heart (AL amyloidosis is the other common type of amyloidosis which may affect the heart). However, abnormal heart rhythms are common in senile systemic amyloidosis and some patients may need a pacemaker. Fluid balance Around 50% of patients with senile systemic amyloidosis also experience carpal tunnel syndrome - tingling and pain in the wrists, pins and needles in the hands. Carpal tunnel syndrome often appears 3-20 years before the symptoms of heart disease and in these individuals it is caused by ATTR amyloid deposits in the wrists. Fluid excess can be avoided by careful attention to the 3 Ds: Nearly one in ten of the patients seen at the NAC because of senile systemic amyloidosis have experienced no symptoms but were found to have amyloid incidentally on routine testing or at the time of an operation for a different complaint. Which tests can help to diagnose senile systemic amyloidosis? The most important principle of treatment for cardiac amyloidosis is strict fluid balance control. Patients should limit their fluid intake. 1. 2. 3. Diet: • fluid intake should be steady and should usually not exceed 1.5 litres per day • salt intake should be strictly limited Diuretics: • diuretics (water tablets) such as furosemide and spironolactone help the body to clear excess salt and water via the urine • removal of excess fluid from the body leads to reduced ankle swelling and breathlessness Daily weights: • every litre of excess fluid weighs one kilogram and several litres can accumulate in the body without it being very noticeable • some patients should weigh themselves daily to identify fluid gain early ECG Echocardiogram Cardiac MRI (CMR) scan Radionuclide imaging (DPD scan) Blood tests: “cardiac biomarkers” (NT-proBNP and troponin) Genetic tests Heart biopsy Abdominal fat / rectal biopsy For more details on each of these tests, see the patient information leaflet on senile systemic amyloidosis, available from the NAC or at www.ucl.ac.uk/amyloidosis/nac Some patients may benefit from other measures such as support stockings for leg oedema (swelling), anticoagulation for patients at risk of blood clots and pacemakers for patients with slow or irregular heart rhythm. Very rarely, heart transplantation may be an option for a patient who presents at an unusually young age (before age 60). Most patients with senile systemic amyloidosis are too elderly to undergo heart transplantation as the risks of complications are high. Outlook Principles of treatment Treatment of senile systemic amyloidosis is symptomatic and supportive for most patients. Standard heart failure medications are often not effective for patients with amyloid deposits in the heart, but the following measures can be very helpful: Senile systemic amyloidosis progresses slowly. A recent study at the NAC found that most patients with senile systemic amyloidosis survived for over 6 years after symptoms started. Furthermore, a number of new drugs for ATTR amyloidosis are in various stages of development. These drugs are not yet available, but they do offer hope for the future. National Amyloidosis Centre News New drugs in development for ATTR amyloidosis Diflunisal: This is a “non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug” (NSAID), a drug class in common use as pain killers, for conditions such as arthritis. Diflunisal is bound by TTR in the blood, which may make TTR less amyloidogenic. However, this drug may have serious side effects and diflunisal use for ATTR amyloidosis is an ‘off-label’ indication so only amyloidosis specialists should prescribe it. Tafamadis: Tafamidis was developed as a specific drug for ATTR amyloidosis. It is bound by TTR in the blood, stabilising the TTR and making it less amyloidogenic. Tafamadis has been approved in Europe for polyneuropathy caused by hereditary ATTR amyloid. But since the evidence that it has a beneficial effect on polyneuropathy is not strong, it has not been approved by the UK NHS or by the FDA in the USA. Tafamadis has not been tested in senile systemic amyloidosis and has not received approval for this indication. Genetic therapies: Small interfering RNA and antisense oligonucleotides are therapeutic approaches that aim to “switch off” the gene for TTR in liver cells, so that TTR is simply not produced. A drug called ALN-TTRsc, which belongs to the small interfering RNA drug class, was shown to reduce blood Issue 3: March 2014 7 levels of TTR by up to 94% in healthy volunteers. ALN-TTRsc is currently undergoing preliminary clinical trials in patients with ATTR cardiac amyloidosis, both senile systemic amyloidosis and the inherited forms of ATTR cardiac amyloidosis. ISIS TTR Rx belongs to the antisense oligonucleotide drug class. ISIS TTR Rx is currently undergoing trials in patients with familial amyloid polyneuropathy, a hereditary type of TTR amyloidosis. Current trials are only assessing the impact of this drug on nerve damage caused by TTR amyloid. It is not being tested at present in patients with senile systemic amyloidosis. Antibody mediated amyloid elimination: Serum amyloid P component (SAP) is a normal blood protein, present in everybody, which is always present in amyloid deposits of all types because it binds strongly to all amyloid fibrils. The Wolfson Drug Discovery Unit has developed a drug called CPHPC, which clears all the SAP from the blood but leaves some SAP bound to the amyloid deposits. After CPHPC has been administered, it is therefore safe and feasible to administer antibodies to SAP which target the amyloid. In experimental models these antibodies trigger the body’s normally very efficient systems for removal of debris from tissues to act on the amyloid. This approach is currently being tested in patients with amyloidosis, in collaboration with GlaxoSmithKline. If it proves to be safe and effective in humans, it will be applicable to patients with all types of amyloidosis including senile systemic amyloidosis. New equipment for studying protein folding purchased by the UCL Amyloidosis Research Fund Amyloidosis is caused by the formation of abnormal amyloid fibril deposits within the body. One of the unsolved mysteries of amyloidosis is the question of how these fibrils all have similar structures, regardless of which of the original, highly varied “precursor” proteins they are formed from. The Wolfson Drug Discovery Unit has recently acquired a new, state-of-the-art, highly sophisticated piece of equipment, an MOS-500 fast modular spectrometer/polarimeter, from BioLogic. Researchers believe this will help to improve our understanding of this conundrum. The new spectrometer was purchased with funds from the UCL Amyloidosis Research Fund and it is already proving invaluable in helping us unravel the processes whereby different “globular” proteins unfold in the early stages of their journey to becoming amyloid fibrils. Dr Patrizia Mangione, working in Professor Vittorio Bellotti’s Protein Misfolding Group, is shown on the left using this new instrument. Until recently she had to travel to Pavia in Italy to have access to this technology. Patrizia says that the new insights into amyloid fibril formation gained from our new equipment will help to bring us a step closer to understanding how amyloid fibrils form, and thus help us in developing new medicines to treat our patients with amyloidosis. National Amyloidosis Centre News 8 Issue 3: March 2014 Fundraising News Father and daughter’s sky-dive in aid of the UCL Amyloidosis Research Fund By Pat Pinchin [based on information provided by Tina Smith] The Smith family from Barbaraville, Easter Ross in the Scottish Highlands, were so devastated by the death from AL amyloidosis of father and grandfather Kenneth Rudkin, that they set about organising a charity event to raise money for the Amyloidosis Research Fund. Kenneth, shown in the picture on the left before he became ill, was father to Tina Smith and grandfather to her daughters. Tina recalls her father as a very kind person who would always do anything for anyone. He loved reading war or spy books and she kept some of his books so that her daughters could enjoy reading them. Kenneth had been unwell for about 10 years with symptoms that had mystified his doctors but had not been diagnosed as amyloidosis. He was uncomplaining and reluctant to seek medical advice, but eventually a frightened Tina intervened. His frequent bouts of uncontrollable diarrhoea, tiredness and breathlessness led him to various consultants at the local hospital in Inverness but it took until November 2012 before suspicion of amyloidosis was raised. The consultant explained that amyloidosis was an illness he knew little about and referred Kenneth to the NAC. None of the family were able to accompany Kenneth on the flight to London. In the company of a carer he went as an emergency patient to the NAC for tests and the special SAP scan. Amyloidosis was confirmed but sadly by this stage, the disease was advanced and Kenneth was too weak for treatment. He was flown back to Scotland and died in Edinburgh Royal Infirmary on 2 January 2013. Kenneth’s family were in shock at the death of their much loved father and grandfather from a rare and incurable disease they had never heard of. They learned that their experience was not uncommon because of the relative rarity of the disease. When patients present with the range of sometimes vague symptoms that amyloidosis can cause, doctors often do not think of amyloidosis. The family promptly decided to do something positive to raise money for the Amyloidosis Research Fund. Their aim was to support the research into new treatments for the disease but also to help promote awareness so as to lessen the frequency of similar late diagnosis experiences for others. One of Kenneth’s granddaughters, Alex, aged 18, is a keen member of Air Cadet Squadron 378, Easter Ross, based in Alness where she lives. Alex’s Dad Paul decided to join her in a 10,000 foot sponsored jump from an aeroplane. Their courageous tandem jump took place at St Andrews in Glenrothes, with full support from Alex’s squadron. The jump was an exhilarating experience for both Alex and Paul and a very proud one for Mum Tina. A total of £600.00 was raised for the Amyloidosis Research Fund. Now Tina is considering an adventurous challenge for herself to continue fund raising for amyloidosis. After the event, Paul said: “The skydive was an amazing experience. It is something I have always wanted to do. As my father-in-law died of amyloidosis earlier this year, the sky-dive was a great opportunity to promote the awareness of the disease and to ask friends, family and colleagues for donations to the Amyloidosis Research Fund." Alex said: “I've always wanted to do a skydive, so I did by raising awareness and money for amyloidosis in memory of my Grandad”. National Amyloidosis Centre News Issue 3: March 2014 9 Fundraising walk in Durham By Malcolm Glass My wife Janice and I were on holiday around 6 years ago when she began struggling with her breathing on a short uphill walk. After number of hospital visits and tests she was diagnosed with “AL Amyloidosis” which had affected her heart. Janice was eventually referred to The National Amyloidosis Centre (NAC) in London. finished 10 hours 18 minutes later, starting and finishing at Wolsingham, a small village in Weardale. I was pleased to receive a certificate and medal for my achievement, not to mention the welcome pie and peas after a very wet day. The terrain is beautiful countryside including open moors and forests. Walkers use public rights of way, and land where access has been given for the event. It rained most of the day and conditions were not great, but everyone enjoyed it and the spirit of the walkers and mutual encouragement was terrific on the day. Drinks and help were offered at various points, and we were pleased to be given delicious cakes and sandwiches half way around. It was a hard day but very rewarding especially when doing it for such a good cause - helping Janice and other sufferers with this cruel disease. On our last visit to the NAC for Janice’s check-up, I was inspired by reading notices on the wall there about the various fundraising events that were taking place and decided to do something to raise funds for the Amyloidosis Research Fund. I am keen on a variety of sporting activities so I signed up for the June 2013 Durham Dales Challenge, an annual challenge walk which takes place in Weardale in County Durham. The walk is organised by members of the Durham branch of the long distance walkers association (LDWA http://www.ldwa.org.uk/challenge_events/show_event.ph p?event_id=11128), and walkers check in at each checkpoint along the way. There is a choice between walking 15 or 30 miles within 12 hours. Around 300 of us set out on 22 June 2013. We started at 9.00 am and I I managed to raise £500 for the Amyloidosis Research Fund. This was mainly from family and work colleagues. There are often charity events taking place at work so asking for more is always difficult. My daughter Michelle set up my fund raising page for me through www.justgiving.com which is a very easy way to generate voluntary contributions. I received a lot of encouragement and support from my family, particularly my two daughters, Heather and Michelle, who follow the progress of the work being carried out by the NAC and the many fundraisers. For me, this event was a start of what I hope will be more fundraising events for the NAC. I am certainly keen to do more and urge others to feel inspired to take part in charity fundraising events for the Amyloidosis Research Fund to help the scientists and doctors discover new treatments to improve the lives of sufferers. For more information on the LDWA (Long Distance Walkers Association) see the website : www.ldwa.org.uk. “Cornwall Tor” charity ride By Pat Pinchin “With a bit of luck someone will have nicked me bike” said one competitor to Miles and Patrick Pinchin before the start of the North Cornwall Tor. Patricia, wife to Patrick and Mum to Miles and Chloe suffers from AL amyloidosis. According to the Met office, it was the wettest day of the year! Just 367 of the 1000 entrants started, and Miles and Patrick were among the hardy who set off. For safety reasons the organisers shortened the 75 mile course and Miles and Patrick completed approximately 52 miles. Unable to take advantage of the greasy downhill stretches to give them momentum on the climbs, they managed to keep pedalling upwards past those who had succumbed to walking. In spite of being well insulated with warm clothing, on reaching Tintagel with temperatures of 5/6 degrees, but which felt more like below freezing, they National Amyloidosis Centre News 10 Issue 3: March 2014 were so cold and wet that they downed a welcome hot chocolate break in a cafe. Many were suffering from hypothermia. When a minibus driver entered the cafe and called out, “I've got room for 15”, he was almost knocked to the ground in the stampede! Some riders called up taxis on their mobile phones. With dogged determination, Miles and Patrick reached the wilds of Bodmin Moor. The north-easterly gale proved a welcome tail wind as they “flew” along the homeward stretch to the finish. “In 50 years of cycling” said Patrick, “this is one of the hardest rides I've ever done; on a par with the fearsome massed start races in Scotland I rode in my 20s!” This is from a seasoned rider who has spent a life-time of racing in time trials from 10 miles to 12 hours! So - well done to father and son duo Patrick and Miles, for rising to the challenge and finishing comfortably in the bronze medal category. With tired legs, feeling “stuffed”, sodden clothes and shoes in bin bags but none the worse for wear, they arrived home ready for a soothing hot shower. They raised £1,335.00 for the Amyloidosis Research Fund. An upcoming fundraising challenge: LEJoG or End to End The End to End (Land’s End to John O’Groats) is one of the classic long distance cycle challenges. It is called LEJoG if ridden North, and JoGLE if ridden South. There are many routes and it has been cycled, walked, hopped, roller skated and even driven on lawn mowers! In July 2014 a team from the National Amyloidosis Centre will be riding the LEJoG. At the moment the team comprises Thirusha Lane (Lead Nurse) and John Plant (a patient with AFib amyloidosis), shown in the picture above. It is hoped that other members of staff, patients or relatives might also join. A few have already committed to ride with the team for a day or so. The route they will take will be over 1,000 miles, and they will climb nearly 16,000 meters (almost twice the height of Mount Everest). Each day they will cycle an average of 71 miles with the longest day at least 83 miles. They will start riding at Land’s End on the 6 July and will finish at John O’Groats on the 19 July. National Amyloidosis Centre News Issue 3: March 2014 11 Why are we doing this? The ride has a number of objectives including: raising money for the Amyloidosis Research Fund through sponsorship, providing an opportunity for patients and relatives to meet up while supporting the team, and importantly, raising amyloidosis awareness across the UK. We hope to use local media in the main towns and cities that the route takes to create a “ribbon of awareness” that stretches from one end of the UK to the other. How can you help? 1. Would you like to ride with the team? If so, make contact with John Plant (john.h.plant@gmail.com) and he can explain what is involved. This route is suitable for someone with a good level of fitness and who wants a challenge. If you do plenty of training beforehand you should have no problem completing the ride. 2. Would you like to join for part of the ride? Having extra people along to lend support would be great. Again, if you are interested please contact John Plant. You don’t need a carbon fibre racing bike to do this - many have ridden successfully and comfortably on light hybrid bicycles. 3. Would you be prepared to meet the team as it comes through major towns on route? This is where we really need the help of patients and relatives. By having a story to tell with local interest the team will contact local media (newspapers, radio, and television) and will arrange to meet groups of supporters to spread news about amyloidosis. These events will also give patients and relatives an opportunity to meet one another. If you are able to meet the team as they ride through a town near you, and if you would be happy to share your story, please get in touch. The more media coverage we can get the more people will become aware of amyloidosis and the work of the NAC. 4. Perhaps you could help by raising sponsorship? We will set up a website and a JustGiving Page. The website http://rideonforamyloidosis.blogspot.co.uk will keep everyone up to date with news of plans, preparations and progress. It will also be a great way to share information with supporters. JustGiving provides a simple and effective method to manage sponsorship. Where will the team be? Day 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 / Date Start 6 July 7 July 8 July 9 July 10 July 11 July 12 July 13 July 14 July 15 July 16 July 17 July 18 July 19 July Land’s End Fowey Morton Hampstead Glastonbury Monmouth Clun Runcorn Conder Green Keswick Moffat Balloch Glencoe Inverness Lairg / The Crask Passes Penzance Plymouth Exeter Wells / Chepstow Hereford Shrewsbury Warrington Lancaster / Ambleside Carlisle Glasgow Crianlarich Spean Bridge Bonar Bridges Altnaharra Ends St Austell Taunton Bristol / Tintern Chester Bolton Windermere Gretna Fort William Thurso Fowey Morton Hampstead Glastonbury Monmouth Clun Runcorn Conder Green Keswick Moffat Balloch Glencoe Inverness Lairg / The Crask John O’Groats National Amyloidosis Centre News 12 Issue 3: March 2014 Times at each location will depend upon progress; head winds in particular can slow things down, but the website will have a link to allow you to track progress every 10 minutes or so making it easy for people to meet the team along the way, especially at any pre-arranged venues where we will be able to work with the media to get publicity. What next? In future newsletters we will tell you more about this exciting challenge, and by that time others may have agreed to help in some of the ways that we have suggested. If you have any ideas of your own that will add to the success of this challenge, especially ones that will create greater awareness, please let us know. Donations To ensure that your donations go directly and exclusively to the NAC, please send directly to us or contact Beth Jones on 020 7433 2802 or beth.jones@ucl.ac.uk. All university based medical research depends on funds that are fought for in open competition (grants) from the Government-funded Medical Research Council and other charitable bodies. Their renewal depends on a successful research programme and the NAC has an excellent track record in this respect. However, there are constant shortfalls and every penny from other sources is received with sincere gratitude, and is used specifically and in its entirety for amyloidosis research. You can make an online donation at: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/amyloidosis/support-us or make a donation by post. A gift aid form is included here and is also available online or from: Beth Jones National Amyloidosis Centre Division of Medicine, Royal Free Campus University College London Rowland Hill Street London NW3 2PF UK UCL Medical School is part of University College London (UCL) which is a registered charity. Due to changes in the Budget nearly all gifts given to UCL now qualify for the Gift Aid Scheme. This increases the amount of the gift by 25% without any extra cost to the donor. It does so by allowing UCL to claim back the basic rate tax paid by the donor. To qualify for Gift Aid the donor must be a UK taxpayer and his/her combined income and capital gains tax bill must equal or exceed the amount UCL claims back on the gift. The gift can be for any amount and applies to one-off gifts and regular gifts made over a number of years. For UCL to claim the tax benefits the donor must make a "Gift Aid Declaration". One declaration will cover all future gifts and may be cancelled at any time. Cheques should be drawn in favour of "UCL Development Fund". This money is then transferred to the Amyloidosis Research Fund together with the reclaimed tax. If a donor does not qualify for the Gift Aid Scheme or does not wish to contribute in this way, cheques should be made payable to: "UCL Amyloidosis Research Fund". Newsletter funded by a bequest from Laura Lock