K&L Gates Global Government Solutions 2011: Annual Outlook An Excerpt From: January 2011

advertisement

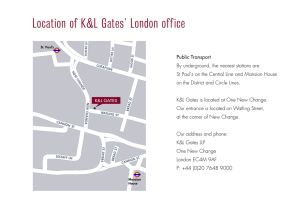

An Excerpt From: K&L Gates Global Government Solutions SM 2011: Annual Outlook January 2011 Government Enforcement and Litigation Government Litigation in 2011: Notable Developments Concerning the State Secrets Doctrine and the Alien Tort Statute 2011 is likely to usher in litigation developments in two areas of particular interest to multinational corporations. • With respect to government contracts, a case pending before the U.S. Supreme Court focuses on whether the government may seek default terminations of government contracts while at the same time limiting the defense of such claims by invoking the state secrets doctrine. • With respect to commercial operations outside the United States, a recent decision from the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit has clarified the extent to which U.S. district courts have jurisdiction over tort claims by foreign individuals directed towards the actions of corporations outside the United States. The Contractors filed suit in the Court of Federal Claims to vacate the initial default determination. A key defense of the Contractors was that the government had caused the delays that ultimately resulted in the termination by breaching its duty to share “superior knowledge” regarding stealth technology that was unknown to the Contractors. The superior knowledge doctrine is a rule of contract fairness that prevents the government from knowingly allowing contractors to pursue a harmful course of action where the government has special knowledge, not shared with the Contractors, which is vital The “State Secrets Doctrine” as Both Sword and Shield In the 1980s, the U.S. Navy sought proposals for the development of a stealth aircraft called the A-12 Avenger. Successful bidders General Dynamics and McDonnell Douglas (“Contractors”) had assumed that they would have access to stealth technology information already developed in other programs for the U.S. Air Force, but this information was not forthcoming, and the Contractors subsequently determined that they could not meet the proposed specifications and time line for development of the A-12. Ultimately, the U.S. Navy sought a default termination, claiming that the Contractors had failed to prosecute the contract and make adequate progress. As part of the default termination, the government demanded payment of over a billion dollars, plus interest. 58 K&L Gates Global Government Solutions SM 2011 Annual Outlook to contract performance. Indeed, prior cases have established that, where the government has this special knowledge, it has an affirmative duty to disclose that knowledge to the contractors. The Contractors attempted to proceed with discovery on this issue, but the government invoked the state secrets doctrine to prohibit such discovery, arguing that inquiry into the alleged superior knowledge would necessarily implicate state secrets. Following a series of appeals to the Federal Circuit and related remands, the trial court ultimately upheld the Navy’s default termination, Government Enforcement and Litigation while at the same time rejecting the Contractors’ defense of superior knowledge, concluding that disclosure of such information would have implicated the state secrets doctrine. By this point, the government default termination had grown into a multi-billion dollar claim against the Contractors. The Supreme Court granted certiorari as to whether the government may prosecute a claim against a party while at the same time invoking the state secrets doctrine to preclude that party from raising affirmative defenses to that claim. See General Dynamics Corp. v. United States (No. 09-1298), consolidated with The Boeing Company v. United States (No. 09-1302). Although the context of the dispute involves contracts with the military, the case has broad due process implications for any party contracting with the government. Should the government prevail, there will be more uncertainty and risk in government contracts, especially for research and development contracts. Should the Contractors in the case succeed, the Supreme Court would likely articulate a broad due process standard under which the government, which traditionally contracts from a position of strength, will be limited in exploiting that position in the contracting process. The outcome of this case should be closely monitored by anyone who contracts with the United States. Corporate Liability under the Alien Tort Statute Corporations engaged in international business should also be aware of a recent decision by the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit with respect to the Alien Tort Statute (“ATS”). Enacted in 1789, and apparently unlike any other jurisdictional statute in the world, the ATS provides in relevant part that U.S. district courts shall have original jurisdiction “over any civil action by an alien for a tort only, committed in violation of the law of nations or a treaty of the United States.” 28 U.S.C. § 1350. The statute was dormant until the 1980s, when the courts began to recognize that the ATS provides jurisdiction over tort actions brought by aliens for violations of the law of nations, such as tort actions for “war crimes.” However, through the mid-1990s, plaintiffs brought suit under the ATS only against foreign individuals, and the question of whether the ATS could be extended to corporations was unclear. In a recent decision, the Second Circuit addressed the unresolved question of whether the jurisdiction granted by the ATS extends to civil actions brought against corporations under the law of nations. Kiobel, et al. v. Royal Dutch Petroleum Co., et al., 621 F.3d 111 (2d Cir. 2010). The Kiobel case involves claims by Nigerian nationals against Dutch, British, and Nigerian corporations engaged in oil exploration. Plaintiffs claimed that the defendant corporations aided and abetted the Nigerian government in committing violations of the laws of nations. The Second Circuit determined that corporate liability for violations of international law is not the “norm of customary international law.” As a result, corporations may not be held liable under the ATS. Although the decision did not preclude ATS suits against individuals, including officers or directors, or otherwise limit corporate liability under other laws, the clear holding in Kiobel is that the ATS does not establish subject matter jurisdiction over ATS claims against corporations. The Second Circuit reached this outcome by examining the “customary” international law, which consists of only those norms that are specific, universal and obligatory in the relations of states. In particular, the court noted that while customary international law imposes individual liability for a limited number of international crimes (including war crimes, crimes against humanity such as genocide, and torture), customary international law has “steadfastly rejected” the notion of corporate liability for international crimes, and no international tribunal has ever held a corporation liable for a violation of the law of nations. While the decision currently precludes jurisdiction over corporations due to the state of customary international law, this area of the law will require continued vigilance. In addition to potential developments in other circuit courts in the United States, should customary international law begin to develop theories regarding corporate liability for torts, the underlying premise of the decision may come under attack. David T. Case (Washington, D.C.) david.case@klgates.com Brendon P. Fowler (Washington, D.C.) brendon.fowler@klgates.com K&L Gates Global Government Solutions SM 2011 Annual Outlook 59 Anchorage Los Angeles San Diego Austin Miami Beijing Berlin Moscow San Francisco Boston Newark Seattle Charlotte New York Shanghai Chicago Dallas Orange County Singapore Dubai Palo Alto Fort Worth Paris Spokane/Coeur d’Alene Frankfurt Pittsburgh Taipei Tokyo Harrisburg Portland Raleigh Hong Kong London Research Triangle Park Warsaw Washington, D.C. K&L Gates includes lawyers practicing out of 36 offices located in North America, Europe, Asia and the Middle East, and represents numerous GLOBAL 500, FORTUNE 100, and FTSE 100 corporations, in addition to growth and middle market companies, entrepreneurs, capital market participants and public sector entities. For more information, visit www.klgates.com. K&L Gates comprises multiple affiliated entities: a limited liability partnership with the full name K&L Gates LLP qualified in Delaware and maintaining offices throughout the United States, in Berlin and Frankfurt, Germany, in Beijing (K&L Gates LLP Beijing Representative Office), in Dubai, U.A.E., in Shanghai (K&L Gates LLP Shanghai Representative Office), in Tokyo, and in Singapore; a limited liability partnership (also named K&L Gates LLP) incorporated in England and maintaining offices in London and Paris; a Taiwan general partnership (K&L Gates) maintaining an office in Taipei; a Hong Kong general partnership (K&L Gates, Solicitors) maintaining an office in Hong Kong; a Polish limited partnership (K&L Gates Jamka sp.k.) maintaining an office in Warsaw; and a Delaware limited liability company (K&L Gates Holdings, LLC) maintaining an office in Moscow. K&L Gates maintains appropriate registrations in the jurisdictions in which its offices are located. A list of the partners or members in each entity is available for inspection at any K&L Gates office. This publication is for informational purposes and does not contain or convey legal advice. The information herein should not be used or relied upon in regard to any particular facts or circumstances without first consulting a lawyer. ©2011 K&L Gates LLP. All Rights Reserved.