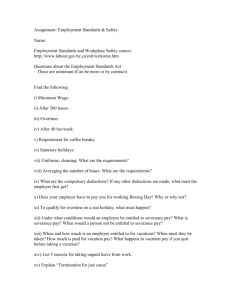

B L ENEFITS AW

advertisement

VOL. 27, NO. 2 SUMMER 2014 From the Editor BENEFITS LAW JOURNAL From the Editor Is Anything Straightforward? US Supreme Court Unanimously Says Severance Pay Is Taxable Wages for FICA P op Quiz: What’s the difference between salary and severance? Answer: Nothing. At least, that was the US Supreme Court’s unanimous conclusion in United States v. Quality Stores, Inc. Overruling the Bankruptcy Court, district court, and US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, the Court held that severance pay is wages that are taxable under the Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA). 572 U.S. ___ (2014). Hidden in plain sight within this case is the fact that tax and benefits law is so muddled, it requires a High Court ruling to answer what seems a fairly simple question. Quality Stores was a farm and agriculture retailer forced by its creditors into Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2001. The company’s misfortunes resulted in the firing of some 3,100 employees, who received a severance payment based on their position, years of service, and base pay. Quality Stores withheld and paid FICA taxes on the severance, but then filed for an IRS refund of these taxes on behalf of itself and 1,850 former employees (the other fired employees didn’t participate). Just over $1 million in taxes was at stake—a lot of money for both the bankrupt company and its out-of-work former employees. Nor was Quality Stores alone: by the time its case reached the Supreme Court, thousands of employers were claiming FICA tax refunds for severance pay. Meanwhile, the IRS was sitting on these refund requests in hope of a judicial victory that would put the issue to bed. (One case went through the Court of Claims and US Court of Appeals From the Editor for the DC Circuit, but wasn’t even cited by the Supreme Court). With the IRS refusing to refund, Quality Stores sued. And, it won in the Bankruptcy Court, district court, and Sixth Circuit, each of which held that severance pay is not FICA wages. The Government appealed and Justice Kennedy, writing for the 8–0 unanimous Court ( Justice Kagan did not participate) reversed, ruling that the IRS was correct and that severance pay is “clearly” wages. At issue was the meaning of a few simple (perhaps deceptively simple) phrases. Internal Revenue Code Sections 3101(a) and 3101(b) say that FICA taxes the “wages received by [an individual] with respect to his employment.” Employment, for FICA purposes, means “any service of whatever nature performed by an employee....” After setting out the basic rule, the Code provides a laundry list of exceptions, none of which involve severance. Reading this rather straightforward definition, there’s a solid argument that severance pay is not taxable wages for FICA. Severance is not paid for services rendered and is not paid “with respect to employment.” Indeed it is the opposite—severance is paid to former employees who lost their jobs. That is entirely different from payments made under a pension or deferred compensation program, which represent compensation that was earned during employment and simply paid out at retirement. Many employers like Quality Stores base the amount of severance paid out on a compensation-like standard, such as the number of years worked. But the severance itself does not represent a payment for past services. It is paid specifically to mitigate the ill effects of being fired and not working; it is more like “un-wages.” Nevertheless, writing for the Court, Justice Kennedy said wages are defined as just about anything paid by an employer to current or former employees by virtue of the employment relationship. Reasoning that an employer provides severance only to its own employees (GE does not pay severance to a fired IBM employee), severance is part of employee compensation. What’s more, the Court was impressed that the Quality Store program’s severance formula was based on title, service, and salary, which are specific employment compensation parameters. The Justices reasoned that qualifies a severance payment as just another component of an employee’s taxable wages under FICA. Besides the wages/un-wages distinction, Quality Stores had another statutory argument in its quiver: the Court’s 1981 decision in Rowan v. United States, which found that free meals provided to workers at an offshore oil rig were not taxable wages for withholding purposes and, therefore, also not wages under FICA. Since then, the Court has strived for “simplicity” and “consistency” in the way it interprets the FICA and income tax withholding rules. Absent a specific exception, that would mean that “wages” would have the same meaning for both FICA and income tax withholding. Quality Stores noted that Code BENEFITS LAW JOURNAL 2 VOL. 27, NO. 2, SUMMER 2014 From the Editor Section 3402(o) of the income tax withholding rules expressly mandated that severance pay should be treated as if it were wages. (Note: technically, this section only applies to supplemental unemployment compensation, but both parties stipulated that Quality Stores’ severance pay was a supplemental unemployment benefit [SUB].) Quality argued that there would be no need for this rule if severance pay actually were wages. Thus, as there is no parallel provision in the FICA statute requiring that severance be treated as if it were wages, severance pay should be FICA tax-free. The Supreme Court smacked this argument down, reasoning that the as if language does not mean severance pay can never be wages—just not always. Justice Kennedy then wrote a meandering history of SUB payment taxation, which concluded that the exception for wage withholding did not apply to FICA. The opinion also hinted that both the IRS and Quality Stores were wrong to assume that severance pay qualified as a SUB. From every angle the Supreme Court looked, severance pay clearly fit within “FICA’s broad definition of wages.” Thus, the IRS should deny the billions of dollars of FICA tax refund claims for severance pay. Okay, now we know that severance pay is taxable for FICA. It took about 15 years, much litigation, and a lot of wasted time by taxpayers and the IRS. All that to figure out how to apply one simple word— wages—to a commonplace event: the payment of severance to fired employees. This type of tax complexity drives practitioners and the IRS to scrutinize every rule and every word for hidden (and frequently unintended) meanings, making even the simple seem complex. As a result, the tax code has to be “clarified” by endless more regulations and rulings. Until Quality Stores, who realized that severance pay was a form of wages in disguise? What Quality Stores really shows is that the Internal Revenue Code consists of too many words and too many rules. The entire Code desperately needs a reboot. David E. Morse Editor-in-Chief K & L Gates LLP New York, NY BENEFITS LAW JOURNAL 3 VOL. 27, NO. 2, SUMMER 2014 Copyright © 2014 CCH Incorporated. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted from Benefits Law Journal Summer 2014, Volume 27, Number 2, pages 1–3, with permission from Aspen Publishers, Wolters Kluwer Law & Business, New York, NY, 1-800-638-8437, www.aspenpublishers.com