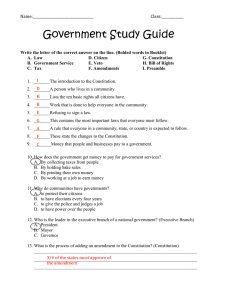

The Rules of the Game:

advertisement