LA ABUELA THE GRANDMOTHER Salvador Ortiz-Carboneres A mi abuela Elisa

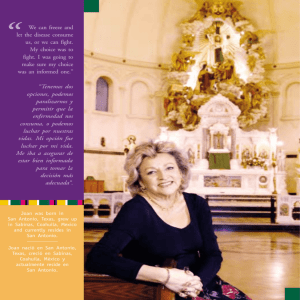

advertisement