Document 13351154

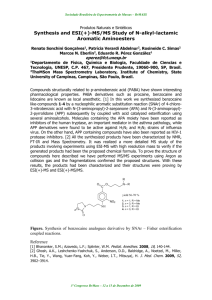

advertisement