Proceedings of 9th International Business and Social Science Research Conference

Proceedings of 9th International Business and Social Science Research Conference

6 - 8 January, 2014, Novotel World Trade Centre, Dubai, UAE, ISBN: 978-1-922069-41-2

Are Stock Market Acquisitions Driven By Misvaluation?:

An Empirical Examination

Kose John, Zhaoyun Shangguan and Gopala Vasudevan

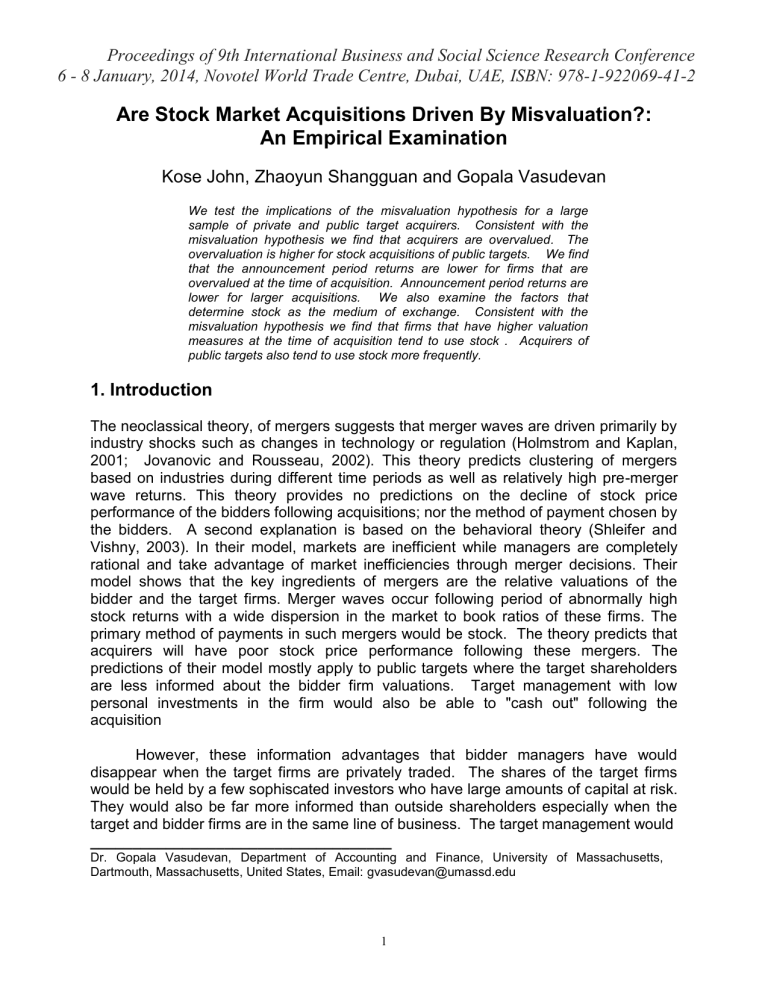

We test the implications of the misvaluation hypothesis for a large sample of private and public target acquirers. Consistent with the misvaluation hypothesis we find that acquirers are overvalued. The overvaluation is higher for stock acquisitions of public targets. We find that the announcement period returns are lower for firms that are overvalued at the time of acquisition. Announcement period returns are lower for larger acquisitions. We also examine the factors that determine stock as the medium of exchange. Consistent with the misvaluation hypothesis we find that firms that have higher valuation measures at the time of acquisition tend to use stock . Acquirers of public targets also tend to use stock more frequently.

1. Introduction

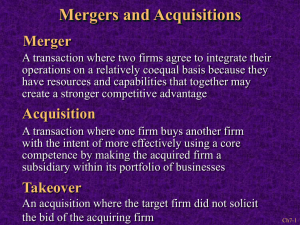

The neoclassical theory, of mergers suggests that merger waves are driven primarily by industry shocks such as changes in technology or regulation (Holmstrom and Kaplan,

2001; Jovanovic and Rousseau, 2002). This theory predicts clustering of mergers based on industries during different time periods as well as relatively high pre-merger wave returns. This theory provides no predictions on the decline of stock price performance of the bidders following acquisitions; nor the method of payment chosen by the bidders. A second explanation is based on the behavioral theory (Shleifer and

Vishny, 2003). In their model, markets are inefficient while managers are completely rational and take advantage of market inefficiencies through merger decisions. Their model shows that the key ingredients of mergers are the relative valuations of the bidder and the target firms. Merger waves occur following period of abnormally high stock returns with a wide dispersion in the market to book ratios of these firms. The primary method of payments in such mergers would be stock. The theory predicts that acquirers will have poor stock price performance following these mergers. The predictions of their model mostly apply to public targets where the target shareholders are less informed about the bidder firm valuations. Target management with low personal investments in the firm would also be able to "cash out" following the acquisition

However, these information advantages that bidder managers have would disappear when the target firms are privately traded. The shares of the target firms would be held by a few sophiscated investors who have large amounts of capital at risk.

They would also be far more informed than outside shareholders especially when the target and bidder firms are in the same line of business. The target management would

____________________________________

Dr. Gopala Vasudevan, Department of Accounting and Finance, University of Massachusetts,

Dartmouth, Massachusetts, United States, Email: gvasudevan@umassd.edu

1

Proceedings of 9th International Business and Social Science Research Conference

6 - 8 January, 2014, Novotel World Trade Centre, Dubai, UAE, ISBN: 978-1-922069-41-2 be willing to spend large amounts of money to be better informed about the bidder’s true value, (Chang, 1998 and Fuller et al, 2002). The target shareholders incentives to be more informed about the bidder would be even greater when they are accepting stock as a form of payment in the acquisition.

First, we examine valuation measures such as the Price to Book Value of Equity and the Relative Price to Book Value of Equity of the acquirer. The market to book value of the acquirer is the market value of equity scaled by the book value of equity.

The relative market to book value of the acquirer is the difference between this ratio and the median market to book ratio of the industry in which the stock belongs to at the time of acquisition. We also examine the run up in the stock price of the acquirer during the

200 days prior to the acquisition announcement. We further examine these ratios based on the type of acquisition (public target versus private target) and the method of payment (stock versus cash).

Next we examine the announcement period returns to acquirers. Our cross sectional regressions relate the acquirer abnormal returns to the degree of overvaluation (the price to book ratio of the acquirer) and other variables such as the relatedness between the acquirer and the target industry, the relative size of the acquisition, the acquirer leverage, the run up in the stock price of the acquirer prior to the acquisition and the method of payment. We also examine the factors that affect the method of payment. Our logistic regressions relate the method of payment to the acquirer price to book ratio, the run up in the stock price during the 200 day period prior to the acquisition and other variables such as the relative size of the acquisition, the acquirer leverage and whether the acquirer is a public firm.

Our univariate results show that the mean (median) price to book value of the public acquirers is lower than the mean price to book value of the private acquirers. We also find that the mean (median) run up in the public target acquirers is lower than the mean (median) run up in the stock price of the private target acquirers. We find similar results when we use the relative price to book ratio. Consistent with the misevaluation hypothesis we find that the mean (median) price to book ratio of cash acquirers is lower than the mean (median) price to book ratio of stock acquirers for both public and private targets. The mean (median) run up in the stock price of stock cash acquirers is also lower than this ratio for stock acquirers. Consistent with the misevaluation hypothesis we find that firms that are potentially overvalued with higher price to book ratios and higher run up in the stock price at the time of acquisition are more likely to use stock as the method of payment. We further find that acquisitions where the target is relatively larger are more likely to use cash as the method of payment.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the prior research. Section 3 discusses the data and methodology. Section 4 reports the results for the study and Section 5 has the summary and conclusions.

2

Proceedings of 9th International Business and Social Science Research Conference

6 - 8 January, 2014, Novotel World Trade Centre, Dubai, UAE, ISBN: 978-1-922069-41-2

2. Prior Research

The neoclassical theory of merger has managers acting on behalf of shareholders making acquisitions that increase firm value. Holmstrom and Kaplan,

(2001) and Jovanovic and Rousseau (2002) develop a model where technological changes result in a dispersion of Tobin's q ratios with high-q firms taking over low-q firms. Their theory predicts no decline in the stock price performance of the firms following the acquisitions nor does it predict any relation between the method of payment for acquisitions and stock returns at the time of acquisition or following the acquisition.

The behavioral theory of corporate acquisitions put forth by Shleifer and Vishny

(2003) assumes that markets are inefficient while managers are completely rational and take advantage of market inefficiencies through merger decisions. The key ingredients of mergers are the relative valuations of the bidder and the target firms. Merger waves occur following periods of abnormally high stock returns when there is a wide dispersion in the market-to-book ratios of these firms. They predict that acquiring firms will have poor stock price performance following these mergers and the method of payment in such mergers would primarily be stock.

The behavioral theory suggests that acquisitions are driven by rational managers who use their overvalued equity to acquire other companies. The market revises their valuation downward at the announcement and the bidder announcement-period returns would be lower in hot markets. They would primarily use stock as the method of payment during hot merger markets. Since these mergers are driven by overvaluation we can expect to find that the stock price performance of the acquiring firms deteriorates over the period following the acquisitions in hot markets.

Rhodes et al (2005) find strong support for the argument that misvaluation is the key component that drives merger activity, the decision to be an acquirer and the medium of exchange. Ang and Cheng (2006) find that firms that are more overvalued tend to use stock as the method of payment. These acquirers tend to outperform similarly overvalued valued firms that do not make acquisitions suggesting that firms that make acquisitions are perhaps increasing their shareholder wealth relative to not making acquisitons.

Moeller, Schlingemann and Stulz (2004) examine acquiring firm returns during the 1998-2001 merger waves versus the 1980’s merger wave. They find that acquiring firms lost approximately $240 billion at the announcement of the acquisition. This is much larger than the $7 billion that acquiring firms lost during the 1980’s. They also find that the firms that suffered huge losses at the announcement also performed poorly following the acquisition.

We expect the overvaluation to be lower private firms targets for several reasons.

For public firms, a takeover financed with stock could be a signal that the acquirer’s stock is overvalued. But for private firms, the smaller numbers of shareholders who end

3

Proceedings of 9th International Business and Social Science Research Conference

6 - 8 January, 2014, Novotel World Trade Centre, Dubai, UAE, ISBN: 978-1-922069-41-2 up with large amount s of the acquirer’s stock have an incentive to thoroughly examine the acquiring firm. A takeover of a private firm financed with stock is a positive signal that the acquirer's shares are fairly valued.

Second stock financed takeovers of private firms is based on increased monitoring of the acquirer following the acquisition. Since the shares of private firms are not held widely, the target shareholders become new outside block holders and this will lead to increased monitoring of the acquiring firm. This can cause a positive stock price increase for the acquirer’s shares at the takeover announcement (Chang, 1998, and Fuller et al, 2002).

Officer et al. (2009) examine the relation between information asymmetry and the medium of exchange in takeovers. They find that the acquirer announcement period returns are higher when the acquirer uses stock to acquire targets that are difficult to value. The use of stocks can mitigate the risk of target overvaluation since the target owners are also sharing the risk with the acquirers (Hansen, 1987). Faccio et al. (2006) examine acquirer announcement period returns for private and public targets for

European acquisitions. They find that acquirer returns are positive for private targets and insignificantly different from zero for public targets.

Chang (1998) finds that the announcement-period returns for the bidder when the target is a private firm is positive for stock acquisitions and zero for cash acquisitions. These are exactly the opposite signs for the bidder returns that Travlos

(1987) finds for acquisitions of public targets.

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Data

We develop a sample of 3485 U.S. firms acquiring public and private targets over the period 1988-2005. Acquisitions included in our sample meet the following criteria:

1. The bidder is a publicly traded firms and information

2. The acquisition information is available in the database maintained by the

Securities Data Company (SDC).

3. Only the first transaction is included per firm-year.

4. Stock return data are available in the Center for Research in Security Prices

(CRSP) database with sufficient returns to estimate the market model.

5. News of the announcement is available on the Dow Jones News Retrieval

Service , and the announcement is not contaminated by release of other information such as dividend or earnings announcements, or capital structure changes around the announcement date of the acquisition.

Our screening of the SDC Database (steps 1 and 2 above) yields 3485 firms.

These include 1531 public acquisitions and 1954 private acquisitions. Table 1 reports the distribution of the 3485 acquisitions by calendar year. We see a substantial increase

4

Proceedings of 9th International Business and Social Science Research Conference

6 - 8 January, 2014, Novotel World Trade Centre, Dubai, UAE, ISBN: 978-1-922069-41-2 in the number of acquisitions over the period. The most activity in our sample, approximately occurs between 1997 and 2000, the lowest number of acquisitions, is during the 1989-1992 period.

Table II reports summary sample statistics. All values shown are for the year prior to the acquisition (year –1). In the year before the acquisition, the mean (median) book value of assets of the public acquirers is $7867.72 ($1,590.56) million. This is considerably larger than the mean (median) book value of asset value of $1933.89

($283.54) for the private targets. The mean (median) price of $989.03 ($166.08) for the public targets is much higher than the mean (median) price of $59.92 ($22.02) for the acquirers of private targets.

3.2. Variables and Methodology

We use multivariate regression models to test a number of predictions implied by the behavioral theory. The following variables are used in the various models (All accounting variables are measured at the most recent fiscal yearend prior to the acquisition announcement):

SameInd - A dummy equal to 1 if the acquirer and the target have the same 3digt SIC code;

Stock - A dummy equal to 1 if the consideration offered by the acquirer is common stock only;

Relsize - The ratio of the target’s total assets to the acquirer’s;

Rel_q - T he ratio of the target’s Tobin’s q to the acquirer’s; Tobin's q is measured as (market value of equity + book value of debt) / (book value of assets);

Acqlev - T he acquirer’s financial leverage measured as total debt divided by total assets;

AcqPTB - The acquirer’s stock price-to-book ratio;

Acqstdr - The standard deviation of monthly returns of the acquirer in the trailing

12 months prior to the acquisition announcement;

AcqReturn - T he acquirer’s stock return for the trailing 200 days prior to the acquisition announcement;

Acqfcf -

The acquirer’s free cash flow from operations measured as the operating income before depreciation and amortization;

CARs – Cumulative abnormal returns from day -2 to day 2 around the acquisition announcement estimated using the market model.

We first examine the PBV, Relative PBV and the Run-up in the acquirer stock price during the 200 days prior to the acquisition. The behavioral theory would predict that the acquirer firms would have high values of PBV, Relative PBV and the Run-up.

We next examine the stock price reaction to the announcement of acquisitions, using the standard event-study method of Brown and Warner (1985) to compute the daily excess returns. Average daily abnormal returns are computed in a two-step

5

Proceedings of 9th International Business and Social Science Research Conference

6 - 8 January, 2014, Novotel World Trade Centre, Dubai, UAE, ISBN: 978-1-922069-41-2 procedure, using stock price data from CRSP. The market portfolio proxy is the CRSP value-weighted index.

We estimate the parameters of a single-factor market model for each firm using the returns from day –255 to day –46 to estimate each firm’s alpha and beta coefficients. Next , we compute the excess return by subtracting a firm’s expected daily return from its actual return. Cumulative abnormal returns are calculated by summing the abnormal returns over the period from day

–2 to day +2, where day 0 represents announcement of the acquisition.

We also examine the cross-sectional relation between the acquirer abnormal returns, the degree of overvaluation and other acquirer and market variables. The behavioral theory predicts that the market would recognize that some of the bidders are potentially overvalued and will revise their valuation down when the bidder announces the acquisition. Our regression model is as follows:

CARs = fn( SameInd , Stock , Relsize , AcqPTB , Acqlev, Acqstdr , AcqReturn ,

Stock*Public ).

We expect to find a negative coefficient for AcqPTB and AcqReturn because firms with a higher run-up can be potentially overvalued. The behavioral theory predicts that the market will realize that these firms are using their overvalued equity to finance their acquisitions and will revise their estimation of firm value downwards on the announcement of the acquisition.

With respect to the control variables, we expect to find a positive coefficient for

SameInd because there will be more synergies in same industry mergers. The neoclassical theory predicts more mergers to be between firms in the same industry because exogenous shocks improve the investment opportunity set for the acquiring firms. We expect firms to pay with stock when their stock is potentially overvalued and hence we expect a negative coefficient for the dummy Stock . We expect more value to be created in larger mergers and hence we expect a positive coefficient for Relsize . We expect a positive coefficient for Acqlev because they will have fewer managerial incentives to waste their resources in potentially bad acquisitions (Safieddine and

Titman, 1999).

We also examine the relation between the firm variables and the likelihood of using stock to finance acquisition. We employ a Logistic regression model of the form:

Stock =fn( LogTvalue , Relsize , Acqfcf,Cashval,Acqlev , AcqPTB , AcqReturn,AcqPTB*Public,

Public).

We expect a negative coefficient for LogTvalue because larger firms tend to be diversified and would incur lower bankruptcy costs. These firms are also more likely to have more access to debt markets and would more likely finance with cash or debt. We expect a positive coefficient for Relsize . Hansen (1987) predicts that stock financing is more likely as the target’s market value increases. We expect a negative coefficient for

6

Proceedings of 9th International Business and Social Science Research Conference

6 - 8 January, 2014, Novotel World Trade Centre, Dubai, UAE, ISBN: 978-1-922069-41-2

Acqfcf and Cashval because these acquirers have more cash in hand and less need to raise stock to finance their acquisition.

Firms with higher leverage may have lower ability to raise the finances for an acquisition. There can also be more monitoring of the firm with increase in leverage.

Hence, we expect a negative coefficient for Acqlev . The behavioral predicts a positive coefficient for AcqReturn because firms with a higher run-up will potentially be more overvalued and are more likely to finance with stock, (Myers and Majluf, 1984; Hansen,

1987). The behavioral theory also predicts a positive coefficient for AcqPTB because firms with a higher market-to-book ratio can be potentially more overvalued and hence we expect these firms to more likely finance with equity The behavioral positive coefficient for both Public and AcqPTB*Public since acquirors of public targets use their overvalued stock to make these acquisitions.

4. Results

Table III reports the acquirer valuation ratios based on the nature of acquisition

(public versus private) and the method of payment (stock versus cash). The first part reports the results for the whole sample. The mean (median) PBV of the private target acquirers is 3.83 (2.24), considerably higher than the mean (median) value of 3.37

(2.09) for the public targets. The mean (median) value of the relative PBV is 0.63

(0.17), considerably higher than the mean (median) value of 0.55 (0.18) for the public targets. The mean (median) value of the run up in the stock price is 0.39 (0.19) for the private acquirers considerably higher than the mean (median) value of 0.29 (0.17) for the public targets. The mean (median) difference between the two groups is statistically significant (insignificant)

The second part of Table III reports the results for stock acquisitions. The mean

(median) PBV of the acquirers of private targets is 4.81 (2.75), considerably higher than the mean (median) value of 3.73 (2.22) for the public targets. The mean (median) relative PBV of the private target acquirers is 0.85 (0.27) considerably higher than the mean (median) value of 0.66 (0.23) for the public target acquirers. The run up in the stock price is also higher for stock acquisitions of public targets.

Table III also reports the results for the acquirers using cash as the medium of exchange. Unlike the results we reported for the overall sample and the stock acquisitions we find that the differences are not significant for the PBV or the relative

PBV. The only variable that is significantly different between the two groups is the Runup variable. We find that the mean value is significantly higher for the acquirers of private targets.

Overall our results on valuation show that the acquirers of both private and public targets are overvalued at the time of acquisitions. Contrary to our expectations, acquirers of private targets are more overvalued than acquirers of public targets. These differences are much higher for stock acquisitions and there is no difference in the over valuation for cash acquisitions.

7

Proceedings of 9th International Business and Social Science Research Conference

6 - 8 January, 2014, Novotel World Trade Centre, Dubai, UAE, ISBN: 978-1-922069-41-2

The announcement-period abnormal returns for our sample are given in Table

1V. Panel A reports the five-day cumulative abnormal returns (CARs) for our sample of acquirers. For the acquirers of private targets where stock is the medium of exchange, the mean (median) announcement period return is 1.74% (0.16%). For stock acquisitions of public targets the mean (median) announcement period return is -2.4% (-

2.00%), the difference between the two groups is significant at the 1% level. For cash acquisitions of private targets the mean (median) announcement period return is 1.55%

(0.72%). For cash acquisitions of public targets the mean (median) announcement period return is 0.37%(0.03%). The difference between the two groups are significant at the 5% level. Moeller, Schlingemann and Stulz (2004) report a three-day mean positive abnormal return of 1.102% for their sample of domestic acquisitions. Panel B of Table

1V reports the three day CARS. For stock acquisitions of private targets the mean

(median) return is 1.17% (-0.05%). For stock acquisitions of public targets the mean

(median) return is -2.15% (-1.86%), the differences between the two groups are significant at the 1% level. For cash acquisitions of private targets the mean (median) abnormal return is 1.3% (0.49%) and for cash acquisitions of public targets the mean

(median) return is 0.64% (0%). The differences between the two groups are significant at the 5% level.

Table V reports the results of our cross-sectional regressions relating acquirer returns to firm characteristics. For public targets the coefficient of stock is -0.036 and significant at the 1% level. The coefficient of Relsize is negative, -0.015, and significant at the 1% level, indicating that the market expects mergers where the target is larger relative to the bidder to create less value. Consistent with the behavioral theory the coefficient of AcqPTB is negative (-0.003) and significant at the 1% level. The coefficient of Acqlev is positive, 0.004, and significant at the 5% level.

The coefficient of Acqstdr is positive, 0.753 and significant at the 1% level. The coefficient of AcqReturn , the acquirer's return during the 12-month period prior to the acquisition is negative, -0.008, and significant at the 1% level. The adjusted R

2 is 6.9

%.

The second column of Table V reports the results for private targets. The coefficient of Sameind is negative, -0.013 and significant at the 10% level. The co-efficient of Stock is positive, 0.015 and significant at the 5% level. The market expects stock acquisitions of private targets to create more value. The coefficient of AcqPTB is not significant. This indicates that the market does not expect acquisitions of private targets by high price to book firms to create less value. This result is in contrast to the findings that we have for public targets. The coefficient of Acqstdr is positive, 1.002 and significant at the 1% level. The coefficient of AcqReturn is negative, -0.010, and significant at the 1% level. The last column reports the results for the overall sample.

Consistent with the behavioral theory the coefficients of AcqPTB and AcqReturn are negative, indicating that the markets react negatively to acquirers that are potentially overvalued. Consistent with the behavioral theory we also find that the coefficient of

Stock * Public is negative, -0.055 and significant at the 1% level.

8

Proceedings of 9th International Business and Social Science Research Conference

6 - 8 January, 2014, Novotel World Trade Centre, Dubai, UAE, ISBN: 978-1-922069-41-2

Table V1 reports the results of the Logit regression. The first column reports the results for public targets. The coefficient of LogTvalue is positive, 0.146, and significant at the 1% level. The coefficient of Relsize is also positive, 0.701, and significant at the

1% level. Acquirers are more likely to finance with stock for larger targets and when the target is relatively large. The co-efficient of Acqfcf is negative (-4.378) and significant at the 1% level indicating that acquirers with larger amounts of free cash flow are less likely to finance with stock. The coefficient of Cashval is negative and significant at the

10% level. The co-efficients of AcqPTB and AcqRe turn are both positive and significant at the 1% level indicating that these firms that are potentially overvalued are more likely to use stock as the medium of exchange. The second column reports the results for private target acquisitions. The coefficient of Relsize is positive, 0.719 and significant at the 1% level, acquirers of larger targets are more likely to use stock as the medium of exchange. The coefficient of Cashval is positive, 0.029, and significant at the 5% level.

Even though these firms have more cash in hand they use stock as the medium of exchange. One explanation for this is that the shareholders of the target may prefer stock to receiving cash perhaps due to the tax consequences of receiving cash. The coefficient of Acqlev is negative and significant at the 1% level, indicating that firms with higher leverage are less likely to use stock to finance acquisitions. The coefficients of both AcqPTB and AcqReturn are negative and significant at the 1% level.

The third column reports the results for all acquisitions. We find that the coefficient of the dummy for Public , which is set equal to 1 for the acquirers of public targets is positive, 0.811 and significant at the 1% level indicating that acquirers of public firms are more likely to use stock to finance acquisitions.

The results of our Logit regressions offer support for several theories.

Consistent with the behavioral theory and Myers-Majluf (1984), the coefficient of AcqReturn and

AcqPTB are both positive and significant at the 1% level. Firms that are potentially overvalued are more likely to finance with stock. Consistent with the debt capacity theories the coefficient of Acqlev is negative and significant at the 1% level for all regressions. We also find that acquirers of larger targets are more likely to finance with stock.

5. Summary and Conclusions

The misvaluation suggests that merger waves occur due to overvaluation of bidder firms. These acquiring managers use overvalued equity to make acquisitions.

The tendency to finance with stock would be more prevalent among over valued firms and acquirers of public targets. In this study we examine the implications of the behavioral theory using a large sample of public and private target acquisitions.

Consistent with the misevaluation hypothesis we find that the mean (median) price to book ratio of cash acquirers is lower than the mean (median) price to book ratio of stock acquirers for both public and private targets. Announcement period returns are lower for stock acquisitions, and larger acquisitions. Consistent with the misevaluation hypothesis we find that firms that are potentially overvalued with higher price to book

9

Proceedings of 9th International Business and Social Science Research Conference

6 - 8 January, 2014, Novotel World Trade Centre, Dubai, UAE, ISBN: 978-1-922069-41-2 ratios and higher run up in the stock price at the time of acquisition are more likely to use stock as the method of payment. We further find that acquisitions where the target is relatively larger are more likely to use cash as the method of payment.

We also find that firms that are acquiring public targets are more likely to finance these acquisitions using stock. Acquirers of public targets that have higher free cash flow, lower leverage and higher cash and cash equivalents are less likely to finance using stock. Firms that are overvalued are more likely to use stock as the medium of exchange.

References

Andrade, G; Mitchell, M and Stafford, 2001, New evidence and perspectives on mergers. Journal of Economic Perspectives 15, 103-120.

Ang, J and Y. Cheng, 2006, Direct evidence on the market-driven acquisition theory,

The Journal of Financial Research, Vol 29, 199-216.

Barclay, M. and Warner, J, 1993, Stealth trading and Volatility: Which trade moves prices, Journal of Financial Economics 281-305.

Berger, P.G. and E. Ofek, 1995, Diversif ication’s Effect on Firm Value, Journal of

Financial Economics 37, 39-65.

Berle, A. A. and G. C. Means, 1932, The Modern Corporation and Private Property ,

New York, Macmillan.

Brown, S. J. and J. B. Warner, 1985, Using Daily Stock Returns: The Case of Event

Studies, Journal of Financial Economics 14, 3-32.

Brunner, R.F., 2002, Does M&A Pay? A Survey of Evidence for the Decision-Maker,

Journal of Applied Finance 12, 48-68.

Chang, S, 1998, Takeovers of privately held targets, methods of payment, and bidder returns, Journal of Finance , 53, 773-784.

Comment, R. and G. A. Jarrell, 1995, Corporate Focus and Stock Returns, Journal of

Financial Economics 37, 67-87.

Demsetz, H. and K. Lehn, 1985, The Structure of Corporate Ownership: Causes and

Consequences, Journal of Political Economy 93, 1155-1177.

Faccio, M and R. W. Masulis, 2005. The Choice of Payment Method in European

Mergers and Acquisitions, Journal of Finance 60, 1345- 1388.

Fama, E. and K. French, 1995, Size and Book-to-Market Factors in Earnings and

Returns, Journal of Finance 45, 1045-1068.

Fishman, M.J, 1989, Preemptive Bidding and the Role of the Medium of Exchange in

Acquisitions, J ournal of Finance 44, 41-57.

Fuller, K., Netter, J., Stegemoller, M., 2002. What do returns to acquiring firms tell us?

Evidence from firms that make many acquisitions. Journal of Finance 57, 1763-

1793.

Hansen, Robert G., 1987, A theory for the choice of exchange medium in mergers and acquisitions.

Journal of Business 60, 75-95.

Helwege, J and N. Liang, 2004, Initial Public Offerings in Hot and Cold Markets, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 39.

10

Proceedings of 9th International Business and Social Science Research Conference

6 - 8 January, 2014, Novotel World Trade Centre, Dubai, UAE, ISBN: 978-1-922069-41-2

Holmstrom, B and S. Kaplan, 2001, Corporate Governance and Merger Activity in the

United States: Making Sense of the 1980's and 1990's, Journal of Economic

Perspectives , 15 (2), 121-144.

Jensen,M. C., 1986, Agency Costs of Free Cash Flow, Corporate Finance and

Takeovers, American Economic Review 26, 654-665.

Jensen, M. C. and W. Meckling, 1976, The Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior,

Agency Costs and Ownership Structure, Journal of Financial Economics 3, 305-

360.

Jovanovic, B. Rousseau, P. 2002, The Q-theory of Mergers, American Economic

Review 92, 198-204.

Jung, K., C. K. Kim, and R. Stulz, 1996, Investment Opportunities, Managerial

Discretion and the Security Issue Decision, Journal of Financial Economics 42,

159-186.

Lang, L., R. M. Stulz, and R. A. Walking, 1989,

Managerial Performance, Tobin’s q and the Gains from Successful Tender Offers, Journal of Financial Economics 24,

137-154.

Lang, L., R. M. Stulz, and R. A. Walking, 1991, A Test of the Free Cash Flow

Hypothesis: The Case of Bidder Returns, Journal of Financial Economics 29,

315-335.

Loughran, T and J. Ritter, 2000, Uniformly Least Powerful Tests of Market Efficiency,

Journal of Financial Economics 55, 361-389.

Loughran, T. and A. Vijh, 1997, Do Long Term Shareholders Benefit from Corporate

Acquisitions, Journal of Finance 52 (5), 1765-1790.

Martin, Kenneth, J. 1996, The Method of Payment in Corporate Acquisitions, Investment

Opportunities and Management Ownership, Journal of Finance 51, 1227-1246.

Moeller, S. B., F. P. Schlingemann, and R. M. Stulz, 2004, Firm Size and the Gains from Acquisition, Journal of Financial Economics 73, 201-228.

Morck, R., A. Shleifer, and R. W. Vishny, 1990, Do Managerial Objectives Drive Bad

Acquisitions? Journal of Finance 45, 31-48.

Myers, S.C and N.S. Majluf, 1984, Corporate Financing and Investment Decisions when

Firms have Information that Investors do not have, Journal of Financial

Economics 13, 187-221.

Officer, M., Poulsen, A., Stegemoller, M., 2009. Target-firm information asymmetry and acquirer returns. Review of Finance 13, 467-493.

Rau, P. R. and T. Vermalen, 1998, Glamour, Value and the post-acquisition performance of bidding firms , Journal of Financial Economics 49(3), 223-253.

Rhodes-Kropf, M, D.T. Robinson and S. Viswanathan, 2004a, Market Valuation and

Merger Waves, Journal of Finance , 2685-2718.

Rhodes-Kropf, M, D.T. Robinson and S. Viswanathan, 2005, Valuation Waves and

Merger Activity, the Empirical Evidence, Journal of Financial Economics 77, 561-

603.

Rosen, R, 2006, Merger Momentum and Investor Sentiment: The Stock Market

Reaction to Merger Announcements, Journal of Business 79, No 2,

Safieddine, Assem and Sheridan Titman, 1999, Leverage and Corporate Performance:

Evidence from Unsuccessful Takeovers, Journal of Finance 54, 547-580.

11

Proceedings of 9th International Business and Social Science Research Conference

6 - 8 January, 2014, Novotel World Trade Centre, Dubai, UAE, ISBN: 978-1-922069-41-2

Servaes, H., 1991, Tobin’s Q and the Gains from Takeovers, Journal of Finance 46,

409-420.

Shleifer, A and Vishny, R, 2003, Stock Market Driven Acquisitions, Journal of Financial

Economics 780, 295-311.

Travlos, N.G., 1987, Corporate Takeover Bids, Methods of Payment and Bidding Firm’s

Stock Returns, Journal of Finance 42, 943-963.

12